There are a whole lot of angles for telling a personal story, so why do people always do it in the same way? The debate about autofiction’s place in the modern storytelling landscape is a boring one, but there is something to be said about the mundane mode of delivery—transforming your real life into art is never really going to come close to capturing truth in its entirety, so why pretend otherwise? The People’s Joker is a lot of things, delivered in a lot of different ways, but all of that is window-dressing for getting at something more absurd, upsetting, and triumphant than any of the twists and turns within this experimental anti-comedy superhero screed: the truth.

The fact that I, or anyone else, gets to see this film is itself a minor miracle. Filmmaker and star Vera Drew—whose experience working with comedy staples like Comedy Bang! Bang! and Abso Lutely is evident throughout The People’s Joker far beyond voice cameos from Scott Aukerman and Tim Heidecker—could not have been surprised when, after the film first premiered at the 2022 Toronto International Film Festival, her debut feature received a significant amount of backlash from DC Comics rights holder Warner Bros. To say that her many depictions of their prized intellectual property push the boundaries of “good taste” is to put it mildly, and despite the fact that parody is meant to be protected in such situations, Warner Bros did their best to make sure the world would never see The People’s Joker.

I consider myself pretty lucky, then, to have defied their wishes. Even before diving further into what makes The People’s Joker truly special, this film is a massive creative achievement. Shot entirely in front of green screens with the help of dozens of animators and artists, not a single frame of this movie is boring. Bewildering, yes, but never boring. We have animated spoofs for Batman Forever (not to mention an opening dedication of Drew’s film to its gonzo director, Joel Schumacher), a superstar clown comedian played by Tim and Eric alum David Liebe Hart, a crudely animated Lorne Michaels voiced by Maria Bamford, and vats of fast-acting estrogen all existing in intersecting, if not parallel, universes. If you’re expecting the basic tenets of narrative film to carry you through, this movie may not be for you—but if you lock into what Drew and team are doing, this is an absolute smorgasbord for the senses.

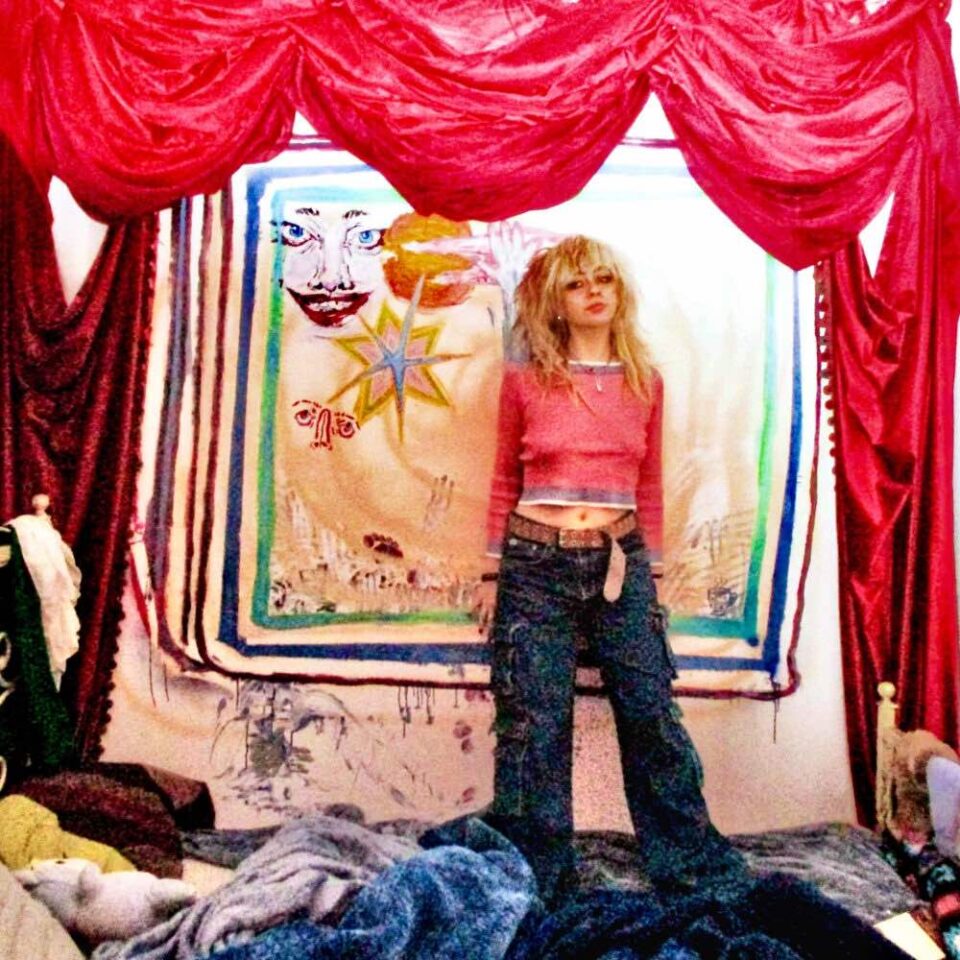

Drew’s performance is the guiding force among the sensory assault that is The People’s Joker, the only thing grounding us in anything close to reality.

But again, all of this is merely the frame for what appears at the center of the canvas: the semi-autobiographical story of Vera Drew’s own journey as a trans woman. Though the film itself pokes fun at the familiar narrative arc of self-discovery, Drew’s story is full of nuance. Using the framework of the Joker’s journey from a lonely boy raised in a broken home in the Midwest to anti-comedy iconoclast in a world of smile-inducing drugs and strict comedy law, Drew shares the very real moments of confusion, shame, and ecstasy that come from wrestling with things like trans identity, familial love, overmedication, abusive romantic relationships, and navigating the legality of comedy. So much of this film is absurd, so much of it genuinely hilarious, that the moments of true pathos almost sneak up on you. And Drew is a big reason why—her performance is the guiding force among the sensory assault that is The People’s Joker, the only thing grounding us in anything close to reality.

It’s not an easy feat to fuse highwire, absurdist parody with heartfelt confessional storytelling, and the smartest thing Drew does in this regard is embrace the mythology inherent in the story of the Joker, the Batman, and the like. By turning her story into myth, she’s externalizing things that, by their nature, often remain internal for longer than one might hope. Like the experimental comedy of someone like Maria Bamford, The People’s Joker achieves directness by being anything but. Almost everything within the frames of the movie is synthetic, but so is everything else in every frame of every movie, coming-of-age or otherwise. By doubling down on that artificiality, and by wrapping everything in layers of absurdity, farce, and obscurity, Drew is leveling the playing field for the story of her own life and identity, which she even admits late in the film still evades her grasp. Warner Bros can fight it all they want, but this Joker is about something much larger than ownership, depiction, or IP. And for that, it belongs to the people.