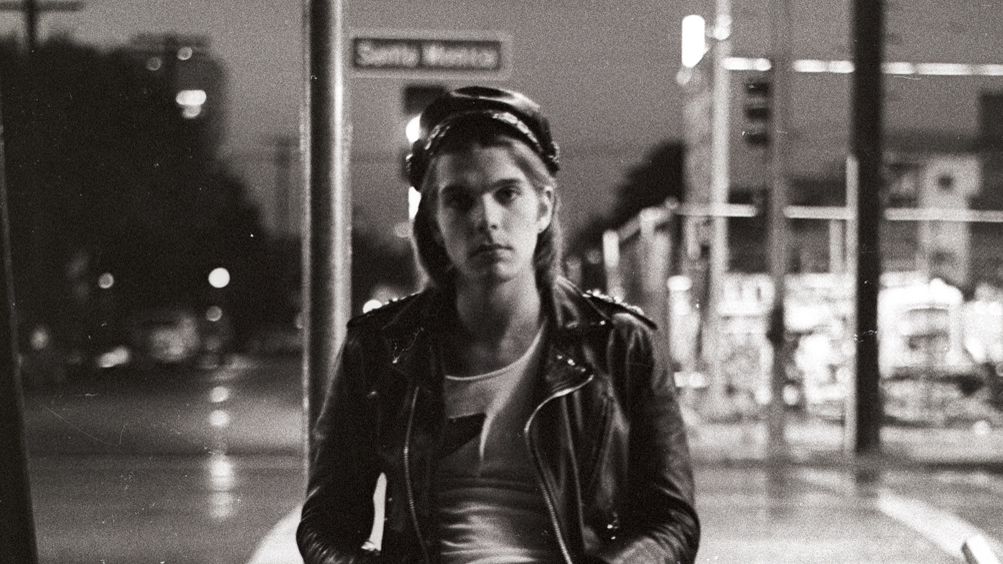

There was nothing ambiguous about Smokey.

John “Smokey” Condon and producer EJ Emmons met while floating through the ether with The Doors. Smokey was a member of the band’s entourage and Emmons was a roadie for the post-Morrison version of the group. They fell for each other, and they started making music, using Condon’s nickname as their moniker. The duo were backed up by a rotating cast of Los Angeles scenesters, and they played mutant hybrids of glam rock, experimental synth punk, and satirical disco. Now, their recorded output has been collected for the first time on the new retrospective How Far Will You Go: The S&M Recordings, 1973–1981, out via Chapter Music.

While many of their peers in the glitter-rock scene played around with androgynous looks, the music of Smokey was explicitly homosexual from the start.

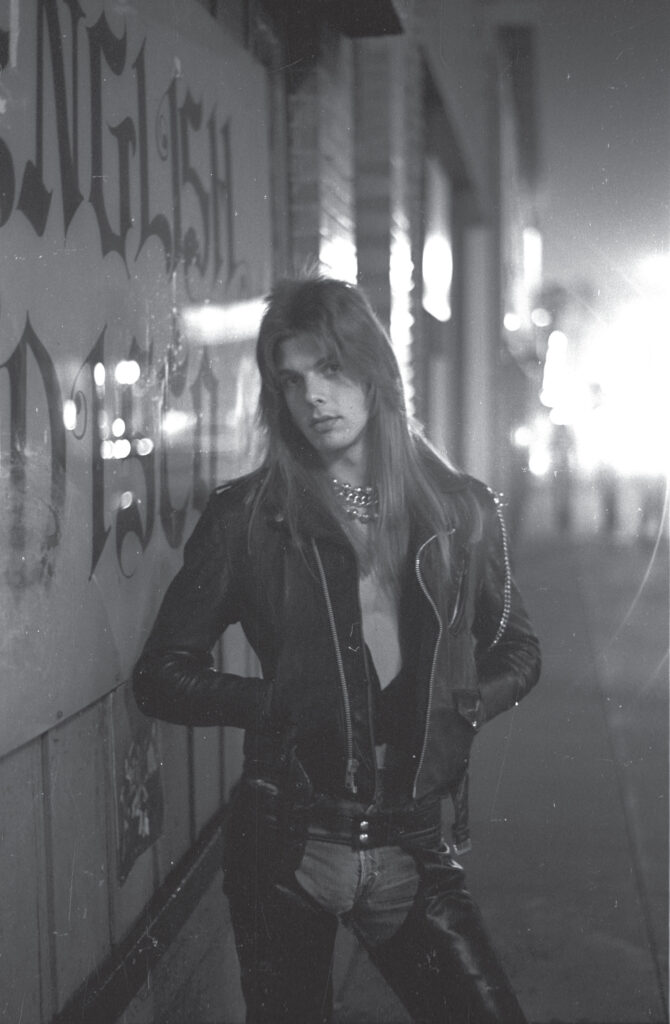

While many of their peers in the glitter-rock scene played around with androgynous looks, the music of Smokey was explicitly homosexual from the start. Their first single, “Leather,” explores Smokey’s experiences in leather bars. “Miss Ray,” the flip side, is dedicated to a drag queen he roomed with in Baltimore, where he’d lived as a teen, engaging in political activism and partying with the John Waters crowd before moving to New York, and ultimately Los Angeles. Rock stars like David Bowie and Iggy Pop might have publicly employed less-than-straight personas, but Smokey was fully out, grooving over the prime glam of “Leather” like Lou Reed at his most salacious: “Cowboys, they make him jump up and scream / Squirm and wiggle and you know what I mean.” There’s no mistaking what Smokey is getting at.

“You could dance around the fringes, but we were putting it in people’s face,” Smokey says of the group’s early days in Los Angeles.

“Way too much to the point,” Emmons adds, laughing.

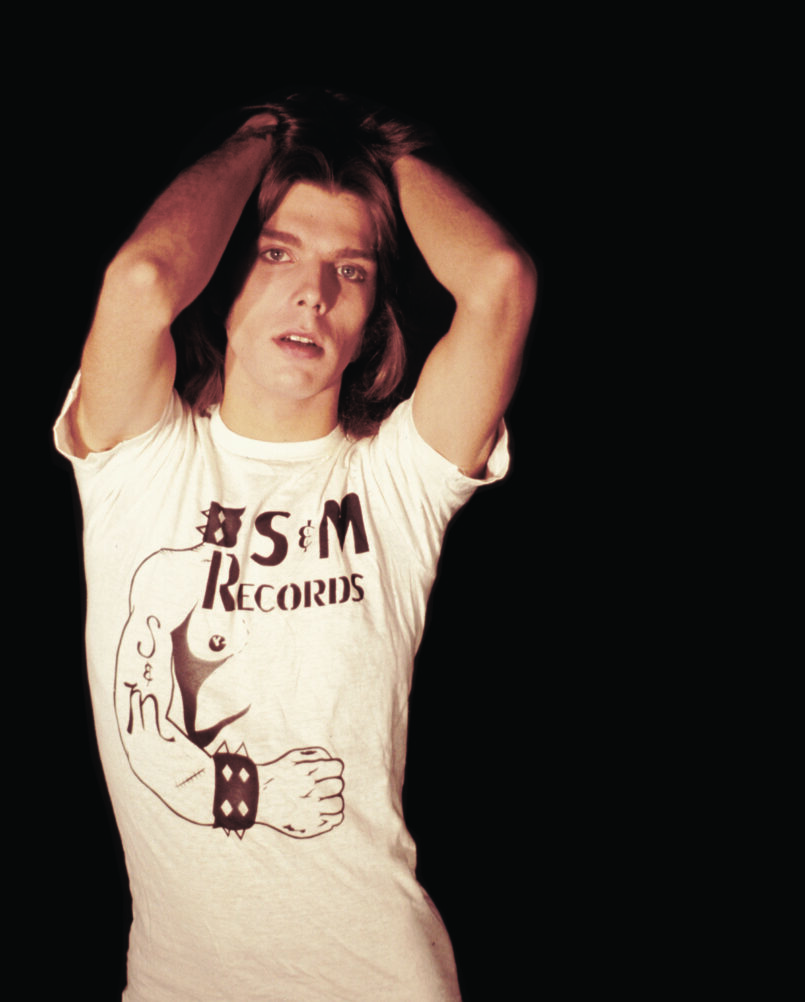

Originally, the duo hoped to score a major label deal. Their prospects looked good. They were regulars at LA disc jockey Rodney Bingenheimer’s popular Sunset club English Disco, and Emmons was well connected in the industry, working in the city’s best studios and holding down jobs at labels like Paramount and Casablanca. Initially, they cut singles to hand off to major-label A&R men, but after meeting resistance because of their “too gay” image, they formed a private-press label, S&M Records.

If you’re at a label, you’ve got responsibilities that are different. You sure don’t want to lose your job because you decided to back some fag, you know?

“We would get this kind of cold shoulder at the labels, but people who would have actually bought the records were perfectly happy with us,” Emmons says. “It wasn’t too much for them… If you’re at a label, you’ve got responsibilities that are different. You sure don’t want to lose your job because you decided to back some fag, you know?”

“People didn’t want to step out on that ledge and back us,” Smokey explains. “The people that have come out in the years since were very closeted in Hollywood. They were really afraid.”

The group pushed on, releasing records on S&M in earnest. They secured distribution in the iconic Tower Records store on Sunset, where they proved steady sellers, and garnered positive press in local magazines. Legendary rock writer Phast Phreddie described one single, the disco dirge “DTNA” (“Dance the Night Away”) as the “…Ohio Players performing Metal Machine Music. It’s very obnoxious and bitchen.” Around town, industry figureheads like Phil Spector and Elton John expressed admiration, but the duo stayed underground, unable to break into the mainstream.

Smokey and Emmons’ willingness to experiment musically was as blatant as their sexuality.

Not that the mainstream would’ve known what to do with them. Smokey and Emmons’ willingness to experiment musically was as blatant as their sexuality. “Strong Love” features a throbbing synthesizer over a driving beat. “How Far Will You Go…?” is woozy funk, with blues guitar accompanying Smokey’s lyrics about David Geffen (he once vomited on the producer, How Far Will You Go’s liner notes detail) and other would-be star makers on the West Coast. “Topanga” sounds like a warped Tin Pan Alley number, while “Fire” is a twisted, bass-heavy rock anthem. Occasionally, Smokey’s songs are alarmingly tender, like on the new wave “I’ll Always Love You” and the gorgeous “Topaz”—a love song written for Emmons that sounds like it could have been pulled from Ariel Pink’s catalog.

While it’s easy to view the songs from a political or sociological angle—out gay men making daring music—Smokey and Emmons say it simply came to them. “We were just playing rock and roll at the time and I was just singing lyrics that I knew,” Smokey says. “These were things that I knew about. I wasn’t an angry young man, I just wanted to sing and EJ just wanted to cut records. We were just out there doing what we felt we wanted to do.”

“There were no politics at all,” insists Emmons. “We were just doing what we felt like doing. There wasn’t a lot of forethought. I can understand the political connotations in the light of recent happenings, and it does fit…but I’m damn sure we weren’t thinking about that then.”

Smokey and Emmons soon found themselves surrounded and backed by emerging talent. The list of people who played in the group reads like a who’s who of the ’70s rock scene: soft rocker Gordon Alexander worked with them; James Williamson of The Stooges played guitar for a few sessions; Hunt and Tony Sales (who played on Iggy Pop and Williamson’s Kill City) served as Smokey’s rhythm section; King Crimson guitarist Adrian Belew joined in. Perhaps most interestingly, the live incarnation of Smokey once included bassist Kelly Garni and guitarist Randy Rhoads, who’d go on to form Quiet Riot together. Later, Rhoads played his way into legend as Ozzy Osbourne’s guitarist, writing the riff for “Crazy Train” before dying in a plane crash in 1982.

“We must have met [Randy Rhoads] at Rodney [Bingenheimer’s English Disco],” Emmons says. “A lot of the musicians we met were through Rodney.”

Though the future Quiet Riot members aren’t featured on the record, “We played a couple of gigs with them,” Smokey says. “They were very young—I was in my early twenties and they were in their late teens. They were very green, naive. Very talented, the both of them.”

“EJ and I had both reached a point where we had our chops down and we were good at what we did… Those [recordings] kick ass.”

Rhoads didn’t play with Smokey long, but the teenaged guitarist made a big impression with the band. “We played an American Legion hall in Burbank and people were fainting in front of Randy and I,” Smokey says. “A riot broke out, the police were called. When Randy and I played together it was bedlam. It was very, very loud. He had a stack of Marshalls.”

The group continued to experiment, recording a session with local funk group Rare Gems. The resulting tracks are some of the group’s farthest out—the raw “Hot Hard & Ready,” the nearly nine-minute epic “Piss Slave,” and the swooning “I’ll Always Love You.” Smokey considers these last recordings to be their finest. “EJ and I had both reached a point where we had our chops down and we were good at what we did… Those [recordings] kick ass,” Smokey says. But after eight years of plugging away, Smokey was done.

“You do it long enough and you beat your head against the wall so long,” he says. “Sometimes, perseverance isn’t there.” Smokey and Emmons’ relationship soured and the group disbanded, leaving behind a few highly collectible records and rumors that the artist behind the 45s had died—or the even more enigmatic suggestion that he’d never been a real person in the first place.

Emmons continued working in music, but Smokey retreated into what he calls the life of “just a normal guy.” He harbored some bitterness about his band’s legacy. “It took me about ten years to get over the fact that we didn’t make it,” Smokey says, but as time has passed, he feels more and more confident in the band’s creative legacy. He works in the lighting industry, lighting chain stores worldwide. “It’s funny, you know. Sometimes I sit in corporate meetings and I look at people and they have no clue who I was,” he laughs. “I get through some corporate meetings that way.”

Emmons wonders what the group could have done with proper backing—“I think we could have gone places people still haven’t gone,” he posits—but admits that the group’s fugitive DIY drive afforded them freedom that labels would likely have stifled. “Maybe it’s better we didn’t get a deal, because we definitely did get to do what we wanted to do, what was in our hearts at the time,” Emmons says.

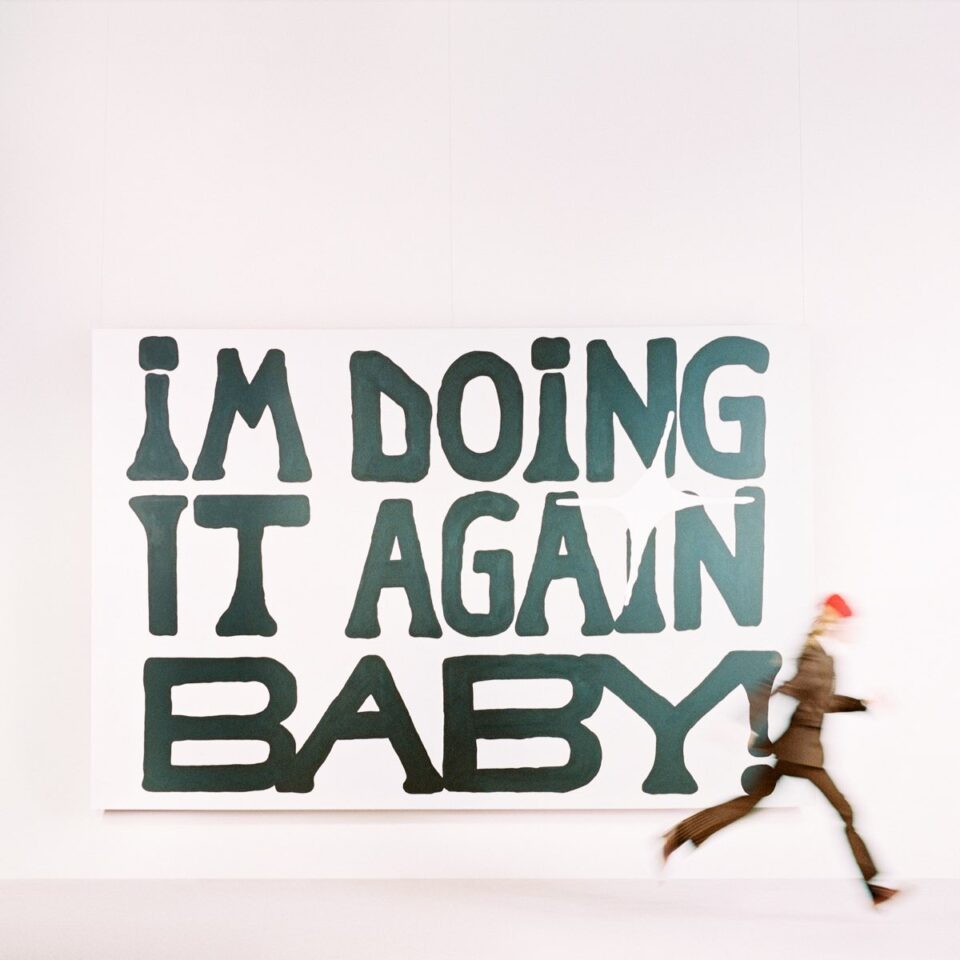

The collection has inspired both creators, and they’re already at work on new Smokey music, after decades apart. “We’re going to do music the way we always did it,” Emmons says.

“And there’s a lot of material to write about these days,” Smokey says. “Oh, my god.” FL