In the late ’70s and early ’80s, no Christmas morning or birthday party was complete without a Star Wars action figure from Kenner Products. Ripping into their gifts, kids the world over would shriek with joy when discovering the latest three-and-three-quarter-inch Han Solo or Darth Vader toy. But before the actual playtime began, those youthful imaginations were immediately ignited and encouraged by the product’s packaging, with its full-color photographs of tiny Ewoks in Endor woods and Imperial Walkers stomping through icy Hoth battles. For its ability to transport a young mind to a galaxy far, far away, the packaging was often even more appealing than the toy itself, and for many kids, it suggested the possibility of a never-ending Star Wars adventure in their own bedroom.

The man who photographed the vast majority of these imaginative scenes for the three-hundred million toys that were sold during the original Star Wars trilogy’s heyday was no ILM technician or George Lucas underling. He was Kim David McNeill Simmons, a young photographer who worked in a Cincinnati basement near the Kenner company offices. In 1981, fresh out of graduate school, Simmons offered himself as an assistant to the original packaging photographer, Roy Frankenfield, and came prepared to sweep floors and load his boss’s film. However, Simmons was immediately put to work and started shooting product and building sets from day one.

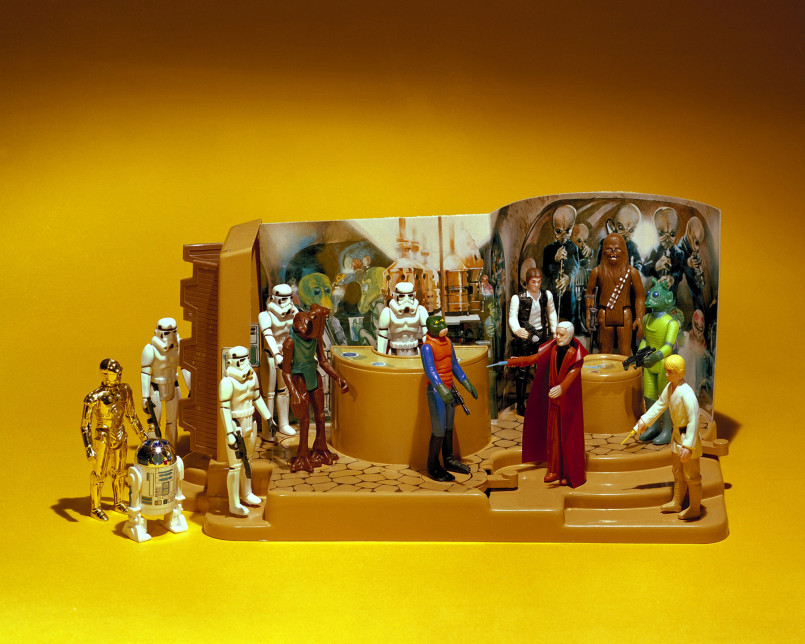

photo by Kim D.M. Simmons

Together, the two photographers would shoot nearly every figure insert, image detail, and packaging background for every officially licensed Star Wars action figure, play set, vehicle, and toy. Receiving shoot briefs from Kenner designers, Simmons and Frankenfield built sets the old-fashioned way, with hobby shop materials and natural elements, arranged lights, and miniatures. Whether they realized it at the time or not, the work they were doing would serve as the imagination blueprints for playtimes far and wide, as their backdrops and settings were emulated by children of all ages everywhere.

Along the way, Simmons had the foresight to obtain all the photographic rights to the images. He bought the photo studio where he and Frankenfield worked in 1988, and retained ownership, copyright, and usage permissions for the film, rescuing the original negatives from a flooded basement. One of the first commercial photographers to embrace digital technology, Simmons enjoyed pushing the envelope of his craft. Throughout his career, he would shoot mostly Star Wars toys and ice cream for grocery companies. As he says now, “There’s no job on the planet better than what I had.” To be sure, one could travel to Tatooine and back and be hard fought to find a better job on any planet.

Today, years after the death of Frankenfield and the transformation of Kenner from Tonka to Hasbro—not to mention the sale of Lucas’s empire to Disney—Simmons lives on, comfortably retired and quietly selling his prints and building models in his rural Ohio home. Here, to celebrate the forthcoming chapter in the biggest movie franchise of all time, FLOOD catches up with The Man Who Shot Luke Skywalker to hear the story behind the original force awakened: childlike imagination.

Simmons building the Hoth battle scene

So, you got your start as an assistant on Star Wars packaging shoots for Kenner?

Kim D.M. Simmons: Yes, and at that time, assistants were typically the guys that handled and loaded the film. That first day I walked in, Roy [Frankenfield] said, “Load-ups are eight-by-ten. We’re going to work on this photo. I’m going to be on the floor. You’re going to be on the ladder.” The ladder was where the camera was. I’d never shot eight-by-ten film in my life, even in grad school. It was too damn expensive—even in those days. But that was it, and after that I never looked back. That first shot was the figure insert that went into the Darth Vader head. It was a blast.

How did you work? Was there a high-security design contact from Kenner bringing you the toys to shoot, since it was well before they appeared in stores?

Even then, it was still tight. At first Roy would go over and get the brief—the job—from the design studio, which was a block-and-a-half away, and eventually I would end up going. I would listen to the briefs and by the time I got back to the studio, I knew what I was going to do. I knew what background they wanted so I was outlining it in my head before I even got off the elevator, and I’d write and start setting up, and that’s why Roy really trusted me to do things right. [The designers] never said, “Nope, this isn’t going to work.” I had changed the way Roy was working. We had a very good relationship—Roy was a great guy and even though I had the book education of a master’s degree, he gave me the practical aspects of the work, especially in dealing with art directors.

I would have seven sets going at the same time. I would shoot one, send the film off; shoot another, send the film off—back and forth. Just going down the line around the studio—the figure lineups, the bursts with all the packaging…I just got it done.

photo by Kim D.M. Simmons

Were you receiving instructions in addition to the designers’ briefs? Did George Lucas or his people ever have feedback for you?

Basically, [the designers] would tell me, “Put these [figures] in a line, make sure they’re not pointed or crossed.” They’re designing the packages as I’m knocking this stuff out. They weren’t used to going so fast. I was way fast. To my knowledge, I don’t think Lucas ever sent anything back to us as photographers.

Were you designing and building the environmental background sets as well?

Oh, yes. I would hit up the hobby shops or I would tell Roy, “I need some sand,” or mulch, or powders. When I first came in, he was using ground-up Styrofoam for snow, and that was atrocious to work with. But that’s where it was really fun, when we would create the different sets. Roy was very good at them. He was able to show me a lot. I had a lot of fun shoots. I pushed every photographic boundary known to mankind when I was doing this because I wanted to learn. You can learn only so much in school.

photo by Kim D.M. Simmons

What would you say was your own personal role in the Star Wars saga? Your work touched so many people—opening up gifts on Christmas morning to see your photos.

You hit the nail on the head. They were all my photos. My role was to take the inspiration of what these designers wanted and put it onto film, to give them what they were designing. I think that it’s the joy that kids got when they saw the toys. They’d see the package and then they’d try to emulate—there’s people today that still try to emulate what I did back then. They e-mail me [photos] and say, “Hey, how am I doing, Kim?” I’ll do a little critique, a little tweak to the ending and send it back to them. Some of these guys are so far advanced now. They’re way beyond me, but they’re still making it look older, like when I shot it back in the day. That was my role, the photographer’s role—to take that vision and give it to the packaging. »

Today, those packages are sought after. The packages became iconic. Even today, people will collect just the packages, not the toy. There’s just something about it. It might be simple, but it gives the kids an idea of playing. It gives them ideas and play value with a toy—direction. Today, kids don’t know how to play, because of computer games. If you give them a sand box, the parents would freak out and say, “Oh my god, there’s a cat around here someplace.” When I was a kid, my dad would bring a whole dump truck of sand and we’d play in it, making tunnels and everything you could imagine. I did dioramas when I was a kid. I didn’t even realize what I was doing, but I enjoyed it.

It was kind of upsetting when we progressed and got into Episode I and all of a sudden that stuff wasn’t there. It was like, “Kim, we want you to put the monster on the sand.” “OK, what about the background?” “Well, we’re going to drop a still from the movie in.” That’s cheating. Kids are not going to be able to do that. One of the last ones I did was the Speeder Bike and we did the whole thing. I did use a background, but I had to build the entire front: everything the vehicle’s on, logs, pebbles. And it blended right into the background. That’s what it’s all about, because kids could do something like that. They could take their toys and create the background, and really let their imaginations go wild. And that’s kind of what the packaging did.

photo by Kim D.M. Simmons

Were you able to keep all of the toys and packages you shot? I’m imagining the world’s luckiest grandchildren, rifling through your attic.

I had everything up until a certain point. Kenner wouldn’t take it all back, because I had everything. I was told, “No, we’d have to pay for storage. They’re yours, Kim.” Then, bad story, somebody made off with a really good deal from me without me realizing the value. But it’s OK, because I have the photos. Some of it is probably better in the hands of a serious collector anyway. They really enjoy these things for what they are and I’ve got the photo. Why do I need the toy? FL

- photo by Kim D.M. Simmons

- photo by Kim D.M. Simmons

- photo by Kim D.M. Simmons

- photo by Kim D.M. Simmons

- photo by Kim D.M. Simmons

- photo by Kim D.M. Simmons

- photo by Kim D.M. Simmons