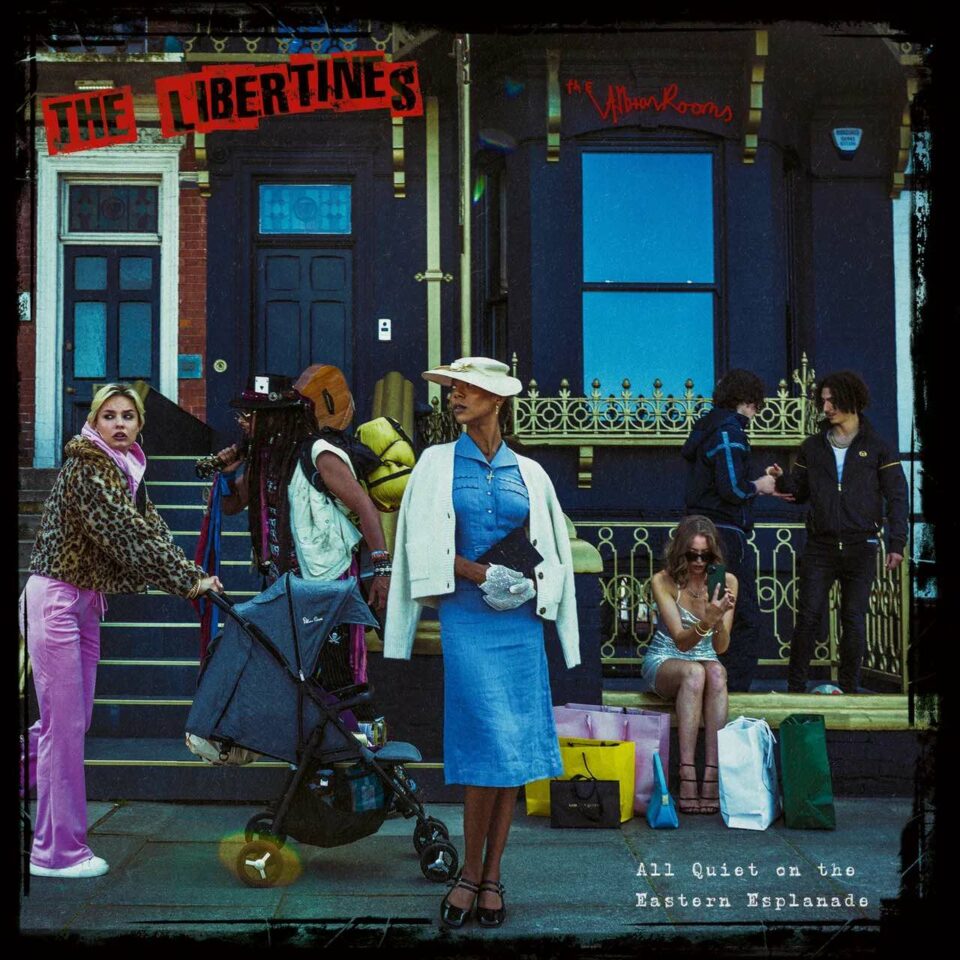

When James Brown made it to Nigeria at the end of 1970, he was touring with a brand new set of players and a brand new label. The members of the group that had supported him in the previous decade had all either left him or been fired. He now had The J.B.’s—one of the planet’s hardest-hitting, funkiest bands—behind him. “Get Up (I Feel Like Being A) Sex Machine” was a new single that year. As was “Super Bad.” His setlist in Nigeria? We don’t know, but we know the crowd was listening, absorbing and finding some kind of solidarity in his deep, all-encompassing funk. Fela Kuti was surely there. That’s been widely documented. But the thousands of others? Thousands of other Nigerians who only months earlier had seen their country finally put an end to a Civil War that had cost hundreds of thousands of lives. Go back to your regular existences, the government urged. Nothing to see here. This time of unrest—when aftershocks of death and destruction are set against an explosive and all-permissive mixture of rock and funk and soul—is explored in Wake Up You!: The Rise & Fall of Nigerian Rock Music 1972–1977, a new two-part compilation released by Now-Again Records and overseen by Nigerian music historian Uchenna Ikonne.

“A lot was already happening in Nigeria but the James Brown visit was definitely a turning point. I can’t say exactly how,” Ikonne says. “Prior to 1970, lots of groups did not record because the labels did not have much interest in them. After 1970, you suddenly find all these rock and soul and funk groups recording. I don’t know if there is a direct influence, but James Brown’s visit did sort of enshrine soul music as a viable form in Nigeria. Prior to that time, people weren’t sure if it was just a fad and something that was going to pass very quickly. But when James Brown came, it made everybody realize that soul was here to stay.”

Soul had been on the Nigerian scene in the years before the Civil War (also known as the Biafran War), which lasted from July of 1967 to January of 1970. But that version of soul was steeped in innocence, and it largely drew from Nigerian highlife and even the Beatles’ early Merseybeat sound. The Nigerian musicians who emerged at the start of the new decade were changed; they were surly and confused and you could hear it in the new music. Take The Hykkers’ “I Want a Break Thru’,” a J.B.’s/Meters funk groove upended by some of the greasiest squawking guitar ever put to tape. Or “Wake Up You,” the Waves song that gives the Now-Again comps their name, which kicks off with a searing solo far from the Tamla Motown grooves of the past and that’s more in line with the harder sounds of Sly Stone, The Yardbirds, and The Jimmy Castor Bunch.

“They were performing music at a time when pursuing a career as a musician in Nigeria was viewed as being maybe two rungs above being a pimp or a beggar.”

This isn’t the first time Now-Again has tested African waters. The label’s work on the Zambian group WITCH’s box set, as well as music from that country’s Rikki Ililonga and others, shows that the southern African nation’s music was headed on a similar trajectory—toward a wild mixture of soul, garage rock, and funk—that was also largely unheard outside of regional radio at the time and has remained mostly obscure to American listeners. Of course, there was one major difference between the two countries. Wake Up You!’s artists were operating in the light of Nigeria’s first star: the charismatic and explosive funk bandleader and outraged native son Fela Kuti.

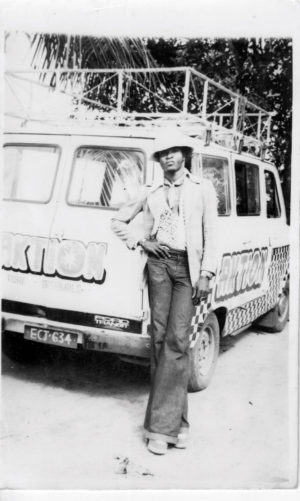

Renny Pearl of Aktion stands in front of his band’s tour bus, 1976

“Since Fela was exploding around the same time with Afrobeat, I think that had a lot of influence on the Nigerian rock scene. There’s much more of a conscious effort to inject an Afro sound into the rock,” Ikonne says.

Part historical record and part mind-blowing musical excavation, this fuzz-soaked comp gathers tracks that have largely been buried for years, illustrating them with archival

images and stories that Ikonne sourced by canvassing Nigeria and researching for most of the last decade.“It really did bring me on an odyssey across the country, just meeting people and getting their stories,” he says. “I’m glad I did it at the time I did because nobody is getting any younger. A lot of the people, I was able to talk to them before they dropped dead. So the material in the book represents the last testament of many of these musicians.”

But it wasn’t the easiest task to fulfill. “The biggest challenge when putting together a project like this is always finding appropriate master materials, because this music, for the most part, has not really been preserved in Nigeria. Many of the record labels have either lost or destroyed the master tapes. When we want to put out a record like this, we have to find copies of the record in good enough condition for us to master directly from the vinyl.”

This kind of informed digging has been what sets apart labels like Now-Again, Numero Group, and Finders Keepers from many of the reissue labels that have been putting impossibly rare or never-released music on store shelves. As Ikonne puts it, “Now-Again has such a depth of vision. They’re not just trying to slap together a couple of songs on a CD and put them out. They really want to create an experience, an event, and that’s something that I want.”

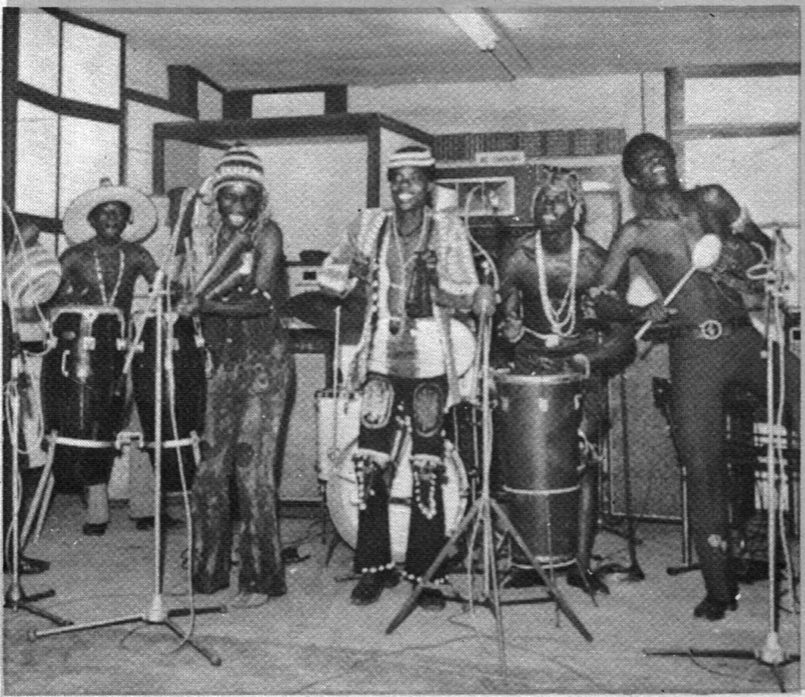

Ofo The Black Company, 1973

Ikonne is no stranger to this type of deep exploration. He was key in getting Luaka Bop to release the extensive box set of synth pioneer William Onyeabor’s albums back into the wild. In that case, he encountered someone nearly adamant about not revisiting his past. He found more willing participants while working on the Wake Up You! project. “Some were very touched by this interest,” he says. “Some felt validated by it in a way, because they were performing music at a time when pursuing a career as a musician in Nigeria was viewed as being maybe two rungs above being a pimp or a beggar.”

Wake Up You! sheds bright light on a scene that was overshadowed by the highlife that preceded it, the Afrobeat that came in its wake, and the war that gave it birth. Ikonne’s copious liner notes provide the context for a greater story of independence, one filled in carefully with vital tracks. Fortunately, it’s hardly the last word. “Wake Up You! has been described as a book, but it’s not a book; it’s a compilation that’s accompanied by a long essay that’s packaged to look like a book,” Ikonne says. “I’m writing the actual book. It’s going to be a three- or four-volume thing that will cover the history of Nigerian music from the 1940s up until the 2000s. That will be my magnum opus.” FL