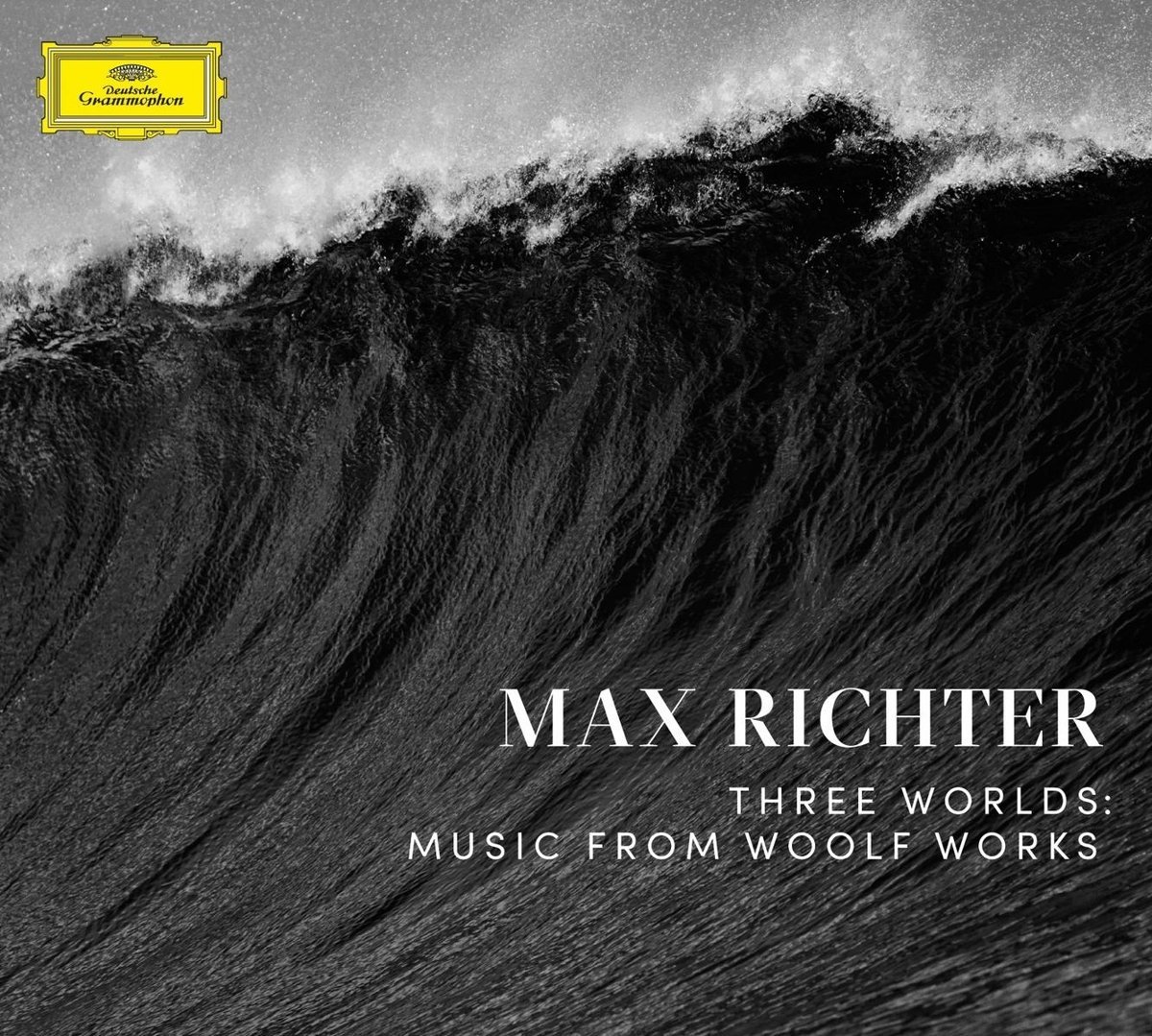

Max Richter

Three Worlds: Music from Woolf Works

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON

8/10

Books have been set to music before, surely. But Wayne McGregor’s 2015 ballet triptych Woolf Works, which took as its starting points three exalted Virginia Woolf novels (The Waves, Orlando, and Mrs. Dalloway), mined the author’s very essence and interpreted it back in a strikingly stark and visceral way. The music was composed by British post-minimalist composer Max Richter, and it’s now been assembled into a proper recording.

Woolf Works opens quite poignantly, with the only known recording of the author, who died nearly seventy-six years ago, but whose literary observation became prophecy: “Words, English words, are full of echoes, of memories, of associations—naturally. They have been out and about, on people’s lips, in their houses, in the streets, in the fields, for so many centuries. And that is one of the chief difficulties in writing them today—that they are so stored with meanings, with memories, that they have contracted so many famous marriages.”

The compositions inspired by Mrs. Dalloway are full of longing—no surprise there—and a sadness for time that has passed and cannot be retrieved. Melancholy strings are weighted with regret and soar with the heavy emotion of uneasy self-reflection. The music that follows in the Orlando section dances with excitement, anxiety, possibility: bows being pulled across the strings of violins as if they were literally charged with propelling us on to meet our destiny. It’s thrilling, and frightening all the same.

And then, The Waves. Indeed, waves crash on the shore as we hear a devastating recitation of the letter Woolf wrote to her husband, Leonard, shortly mental illness overwhelmed her and compelled her to take her own life. “I shan’t recover this time,” she writes. “So I am doing what seems the best thing to do… I don’t think two people could have been happier till this terrible disease came. I can’t fight any longer. I know that I am spoiling your life… Everything has gone from me but the certainty of your goodness.” In the musical interlude that follows, Richter somehow manages to write Woolf’s hopelessness, and surely also Leonard’s devastating pain. Appropriately, it goes on without relent.

It’s difficult to recall compositions with such consuming interpretive power. To be sure, Richter bravely journeys deep into the interior of the fragile, volatile author and her inimitable characters. Be prepared to take the same journey without interruption—and expect it to hurt a bit.