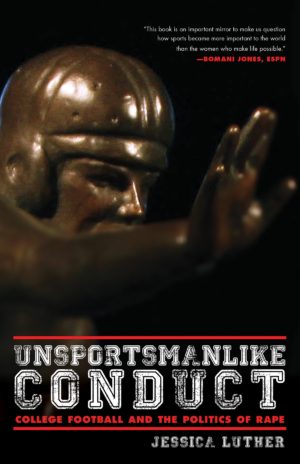

In the past five years, a pair of high-profile rape cases have arisen from the world of college football: Florida State Heisman winner Jameis Winston was accused of raping a woman in Tallahassee and was controversially not charged (a later civil case brought against the university by the plaintiff was settled for $950,000), and Baylor University was discovered to have covered up the assault of seventeen women by nineteen players, with head coach Art Briles subsequently fired. To many these may be the only cases they’ve heard about, or seem like isolated incidents, but for every fan who wants to be able to say, “That would never happen at my school,” Jessica Luther’s Unsportsmanlike Conduct: College Football and the Politics of Rape plainly explains that, no, really, it would, and the systems in place are set to keep it that way.

After emerging as one of the foremost writers on the topic of sexual assault on college campuses, covering specific cases for Sports Illustrated, ESPN The Magazine, and VICE Sports, Luther stepped back to examine the entire culture of rape in college football. Writing about the issue as a whole, she says, has actually drawn less pushback from enraged fans than when she covers a specific program. Her comprehensive analysis leaves no doubt of the systemic problems. “The book has really allowed me to say, ‘I wrote about all the horrible places, all of them, at once,’” she says. “I hadn’t anticipated that and I like that. I would much rather talk about the system than one individual case.”

Unsportsmanlike Conduct is divided into two sections: “The Playbook As It Is” and “How It Could Be.” Luther begins by using the sport’s own imagery of a playing field and playbook to show all the ways that these cases fall into familiar patterns, with coaches, administrators, fans, police, and media playing similar parts over and over to minimize victims and maximize their own interests. Luther’s training as a historian gives her an eye for analyzing the big picture, seeing the ways in which the principals of a specific case run those frequently called plays. She expertly dissects the complexity and nuance of the issue, providing example after example, from big school to small. She is conscious to examine the underlying societal conditioning that colors people’s thoughts on the issue, from racial and gender biases to perceptions about guilt, trauma, and the justice system, before laying out how things could be done differently.

With another college football season behind us, Unsportsmanlike Conduct is an essential offseason read, provoking us to consider one of the worst consequences of this sport’s culture.

As Luther says in the introduction, “It is easy to say that you do not condone this kind of violence; it is infinitely harder to take a hard look at how the very sport you love contributes to a culture that ignores, minimizes, and sometimes perpetrates it.”

You had been doing this kind of journalism for a couple years. How did you come to the decision that it was time to write a book on the topic?

The book is on Dave Zirin’s imprint [Edge of Sports]. He’s the sports editor at The Nation, and he actually asked me to write the book. I didn’t know if I wanted to do that, and it took me a while to decide. I was worried about pushback, because I’m always worried about pushback, and [the] concern [that] there wasn’t enough to say, and/or that two years later no one would care about the topic anymore, [that] there was sort of a flash in the pan around the Winston case and then it would just sort of die off as an issue. [But] I was wrong about all those things, so I’m glad I ended up doing it.

Did you take a systematic approach from the beginning, or was that something that came out of the process?

I always think about things as systems. I’m a trained historian, and in the kind of history that I was doing before, I was trained to look at things systemically throughout history. Once someone teaches you how to look at things systemically it feels like it’s impossible to not see those things. History teaches you to look at patterns across time, patterns in general, the way people repeatedly respond to the same sort of thing, and I think all those things are obvious in the book.

You went to Florida State and use the Winston case as a starting point. Was it easier or harder having that as a lens to look at it through?

“It’s hard to lose something that has brought you immense joy and is tied to your identity for a long time. That has been difficult.”

Well, I don’t know. I don’t know how to compare it—it’s what I know. It’s been hard, though. I am, or I was, a superfan; I had that deep football fandom. We would schedule our lives around football games—you couldn’t go anywhere the weekend of Miami/FSU because you needed to be in front of a television at a certain time. [Or] we’re going to be playing UF right before Thanksgiving, [so] I’ve got to make sure we’re somewhere near a television if we’re traveling. I did all those kind of things; I had the schedule memorized before the season. It’s hard to lose something that has brought you immense joy and is tied to your identity for a long time. That has been difficult.

You break the book up into the two sections. How important was it for you to write that more prescriptive and forward-looking second section?

It was crucial. It was one of the things from the jump where I said to my editor and my publisher that we’re going to have that; I was going to write a section [of solutions] at the end. I actually didn’t expect it would be a third of the book, but I knew that I was going to need—I need hope, to not just be sad. I didn’t want to write a book that was just sad.

In working on the first two-thirds of the book and in all the work you do around this issue, what is the part that stood out to you or surprised you as you went along in your reporting?

photo by Janelle Reene Matous

The thing that bothers me the most and I know what to do with the least is the amount of cases that involve multiple players. I think in the book it’s something like 40 percent are gang rape and it inches toward 50 when you count accessory and witnesses and all sorts of stuff. I don’t know if that answers your question necessarily, but it bothers the hell out of me; everyone should be bothered by that. I think that has a lot to do with sort of masculinity and the bonding and the loyalty and the team-building and whatever the hell is happening there.

But once things have happened and there’s a reaction to it, I think the one that bothers me the most [is] the response of “This is an isolated case, this is nothing to do with the program, it’s no reflection on us, this is just that person”—especially in cases where there’s multiple players involved and everyone’s like, “Nothing to do with the culture of the team.” I can’t believe Tennessee got off the hook so easily, that [Head Coach] Butch Jones got off the hook for what came out about his program. [Ed. note: Last July, the University of Tennessee settled out of court with eight women who claimed to have been assaulted by members of the UT football team. Jones reportedly called one player who attempted to help a victim “a traitor.”]. It blows my mind, but people just buy into this idea of isolation, [and see] these cases in isolation, so much so that they’re willing to overlook systemic issues and believe that. I find that endlessly frustrating.

Your next project is about still loving sports when they don’t love you. How do you do that? Do you still enjoy sports at all?

I love sports. I still every once in a while will watch some football, kind of like an old-habits-die-hard kind of thing. But I think part of it is, I watch a lot of tennis, and I don’t write very much about tennis. I sort of try to isolate myself. I mean, I get it: here’s a sport I love, I don’t want to know anything about it, I just want to watch and play. I get that impulse; it’s much easier to manage all of this.

But I don’t know, I just love sports so much that I can’t imagine not watching in some way. I love competition. [But] I have this particular issue that I care a lot about and I do think of survivors when I’m watching college football in a way that it’s very difficult to continue to watch.

“People just buy into this idea of isolation so much so that they’re willing to overlook systemic issues. I find that endlessly frustrating.”

I also think the whole system is exploitative. I think they should be paying the players, they should be trying harder to make sure they get their degrees and give them a good education. Watching them crash their bodies into each other, knowing what they’re doing to their bodies and their brains, that they’re not going to get medical care when they leave the university… These are all things that have a direct influence on my ability to enjoy watching football. I don’t struggle as much with college basketball in that sense, even though there’s some of that as far as paying and education, and I know some stories there around sexual violence.

But I think with all of these things, any kind of pop-culture consumption in this world, women, people of color, any kind of marginalized group, you just kind of get used to consuming things that aren’t very nice to you. I’m taking in misogyny like all the time. I turn on whatever TV show and they make jokes that belittle women and minimize sexual violence. That’s happening all the time all around me and I don’t know—I guess you just get good at compartmentalizing it. FL