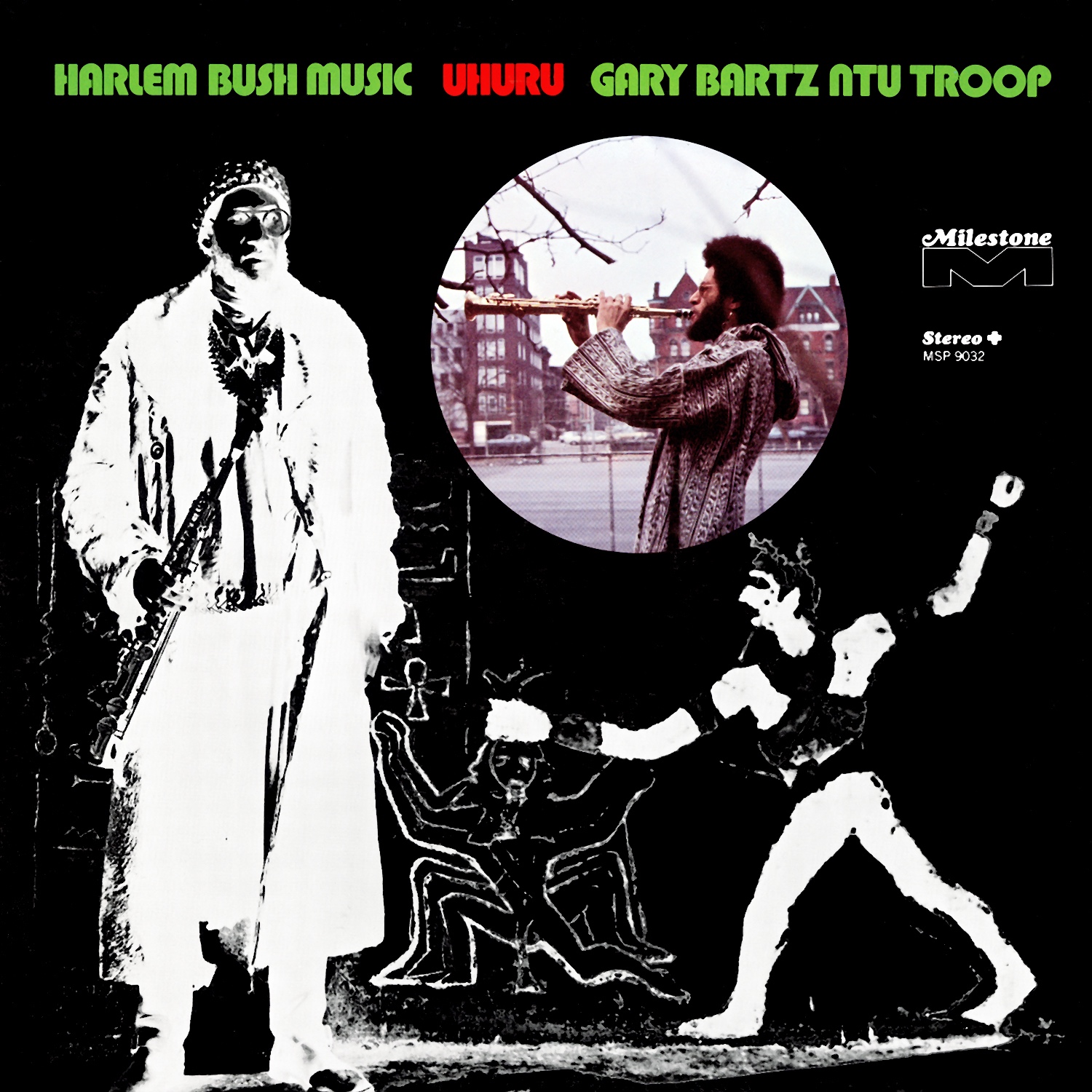

Gary Bartz Ntu Troop

Gary Bartz Ntu Troop

Harlem Bush Music – Uhuru

JAZZ DISPENSARY

8/10

In the notes of Gary Bartz’s Ntu Troop’s Harlem Bush Music – Uhuru, Maxine Bartz shares the words of a friend upon first listening to the 1971 collection of soul jazz: “This is a LIFE album!” Maxine suspected nothing more need to be said to sum up her husband’s aim. Led by the saxophonist Bartz, Ntu Troop aimed to encompass the vastness of the black experience in the early 1970s. Bartz had jazz in his blood; early on, he joined Art Blakey on stage at his father’s jazz club in Baltimore. He studied at Juilliard and cut his teeth playing with McCoy Tyner, Max Roach, Pharoah Sanders, and others, and explored the intellectual landscape of New York’s Lower East Side, hanging out with Allen Ginsberg and Amiri Baraka.

As the ’60s faded, he began pioneering “soul-jazz,” a new fusion that folded together hard bop, soul, funk, free jazz, and polyrhythmic Afro-Cuban music. He formed a new group, Ntu Troop, with vocalist Andy Bey (a favorite of the then-late John Coltrane) at the microphone, the legendary Ron Carter on bass, Harold White on drums, and Nat Bettis on percussion. Bartz was interested in broadcasting a particular worldview, one that was stridently African, anti-war, and cosmically enlightened. He wanted to make music that reflected his experience.

One of two installments in Ntu Troop’s Harlem Bush Music series (Taifa came the year before) 1971’s Uhuru was dedicated to Malcolm X and John Coltrane. You can hear the proud defiance of the former in the grooves of “Uhuru Sasa,” led by Bey’s refrain of “Hell no, we won’t fight your filthy battles.” Similarly pointed is “Vietcong,” which illustrates the direct connection between the civil rights and anti-war movements. Songwriter Hakim Jami’s invocation of the Viet Cong as “a little old man walking through the jungle” who’s “fighting for his homeland” renders the complexities of the Vietnam war a little too idyllically, but it’s easy to see why black advocates might empathize with the Viet Cong as much as US soldiers caught up in a sketchy international conflict. “Why don’t all you foreigners leave these folks alone,” Bey asks, knowing full well that plenty of young black men had been conscripted to fight in the Vietnam War for a country that offered them little to no respect on their home soil.

As for Coltrane, his influence is felt all throughout the record’s questing, strident grooves. Opening song “Blue (A Folk Tale)” takes up the entire first side of the record, bouncing between the vocals of Bartz and Bey and the group’s most energetic bursts. Even farther out is “Celestial Blues/The Planets.” Bey’s voice—warm, full, and clear—plays in tandem with Bartz’s soaring melodies, the combo brewing up a dense blend of funk and jazz underneath them.

Ntu Troop was named for the Bantu word for “unity,” and represented the concept of “unity in all things, time and space, living and dead, seen and unseen.” Fittingly, “Celestial Blues” offers cosmically sage advice: “Expand your mind / Don’t let it wither and die / You’ll find it lifts your spirits high to the sky,” Bey sings. It would be nice to imagine that the message of Ntu Troop would feel antiquated more than forty-five years after Uhuru’s original release, but Bartz’s vivid, jazzy sermon still sounds radical and intense. It’s life music for people just trying to live.