He’d been eyeing the bare concrete surface for quite some time. As always, it stared ahead with static indifference, eight stories above the bustling Lower East Side intersection of Houston and Broadway, to the southeast of Washington Square. He knew that many thousands of people from all over the world buzzed through the crossroads each day. The windowless wall sat in plain view to the masses, screaming out silently to be slammed, and he heard it loud and clear. It wouldn’t be his first attempt. Many flights of stairs had already been climbed, several elevators ridden, each pathway ultimately leading to a securely locked door and patronizing “roof access” sign.

One day, after visiting the office of a magazine in the same building, the young man noticed an open door he hadn’t seen before. He and his cousin packed up their cans and rollers in an inconspicuous fashion and dressed to resemble maintenance workers. He knew they had to act fast before the building was secured for the night. Their final obstacle would be the security guard in the lobby. He walked up to the desk coolly and explained that they were there to perform maintenance in said magazine office, knowing full well that if the guard called upstairs for verification they were screwed. But the guard didn’t call. Something oddly relatable in the eyes of this maintenance worker suggested he had a good reason for being there.

Home free on the illicit rooftop, a thirty-year-old Shepard Fairey rolled out his signature piece: a stylized visage of the behemoth wrestler Andre the Giant, a sort of tangible proto-meme. “OBEY,” it instructed the passersby sardonically. Soon they would all be listening. His hair tousled by Manhattan wind tunnels, Fairey stood at the edge of the rooftop, on the precipice of a brand new millennium. It was the year 2000. He still could see two towers standing tall just a few blocks away, glistening in the synthetic aurora of New York City light pollution. Y2K had come and gone, but the world as he knew it had yet to end.

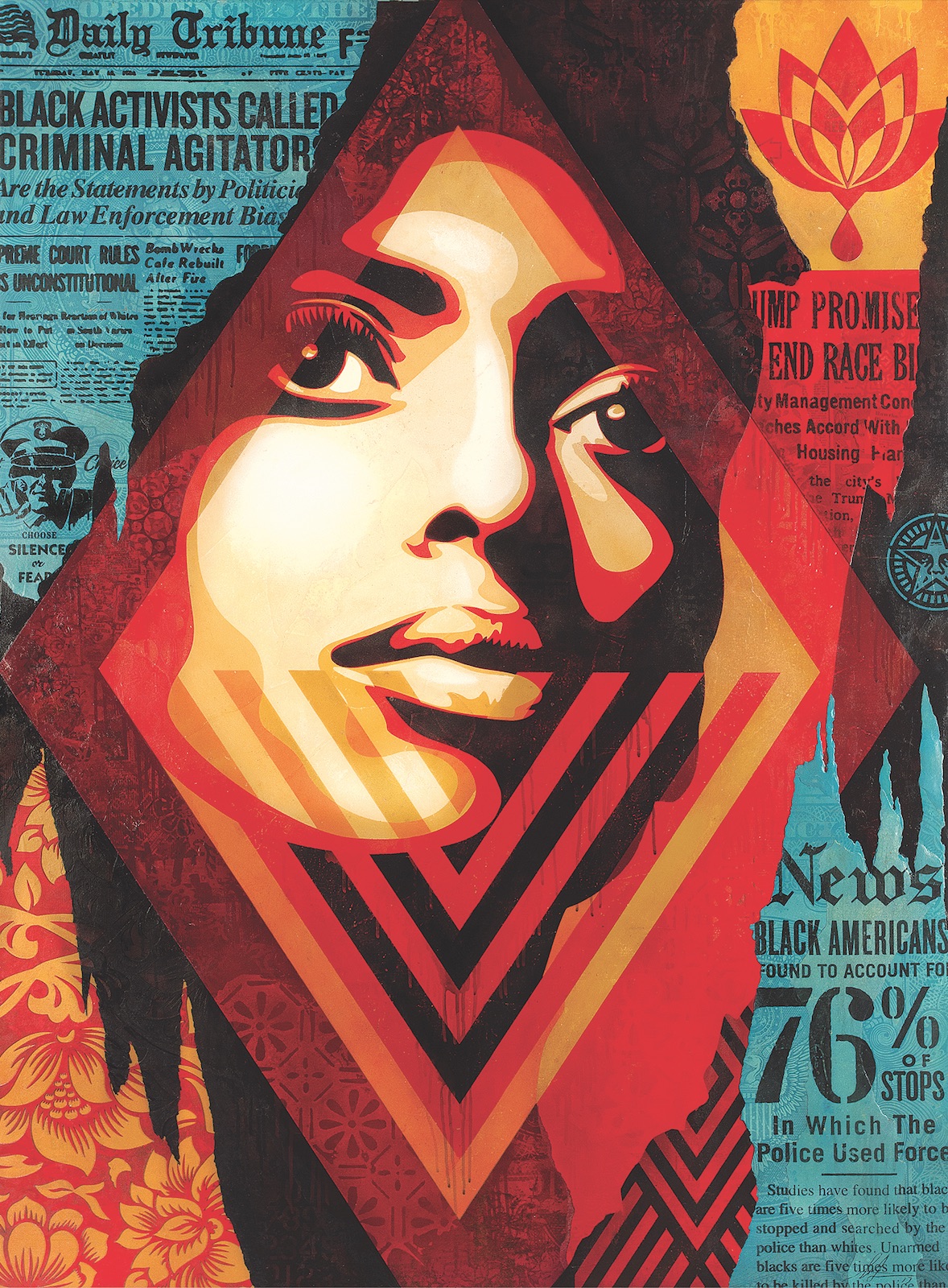

“Bias by Numbers,” 2017

“There have been a lot of intense things,” Fairey says of his graffiti exploits almost two decades later. This past November, he debuted new work at Damaged, his largest-ever solo show in LA. But he wasn’t always so established. “Running from the police, having vigilante citizens pull guns on me, shimmying up drainpipes. But that night was the most thrilling, in good and very bad ways. Afterward, we went across the street to look at it and each put up a couple of stickers. We were promptly arrested by an undercover vandal squad for the stickering. Then, at a later point, they noticed the huge poster many stories above the street, and I had to do some Houdini-like maneuvering to avoid being caught with further evidence that would’ve incriminated me.”

The sleight of hand that Fairey pulled in order to save his work on that memorable evening would pale in comparison to the personal and professional transformation he would achieve in the coming years. He had already been stickering the Andre the Giant image since he was a student at the Rhode Island School of Design in 1989, and was well on his way to helping some of the best-known brands in America use guerrilla tactics to their own marketing ends as a founding member of the firm BLK/MRKT.

“There have been a lot of intense things. Running from the police, having vigilante citizens pull guns on me, shimmying up drainpipes.”

Fairey’s pursuit of the tipping point between public menace and icon of the street-art world continued post-9/11 with countless successful design campaigns, including album covers for Smashing Pumpkins and Led Zeppelin. In 2004, his personal synthesis of street and protest art honed its focus with a series of anti–Iraq War/George W. Bush posters created in lockstep with fellow artists Robbie Conal and Mear One. This progression would lead Fairey to his most notable work to date: a stylized stencil portrait—not entirely unlike his Andre the Giant—in a gradient derived from the colors of the American flag depicting United States Senator and 2008 presidential candidate Barack Obama. Beneath his likeness in block sky-blue letters read one word: HOPE.

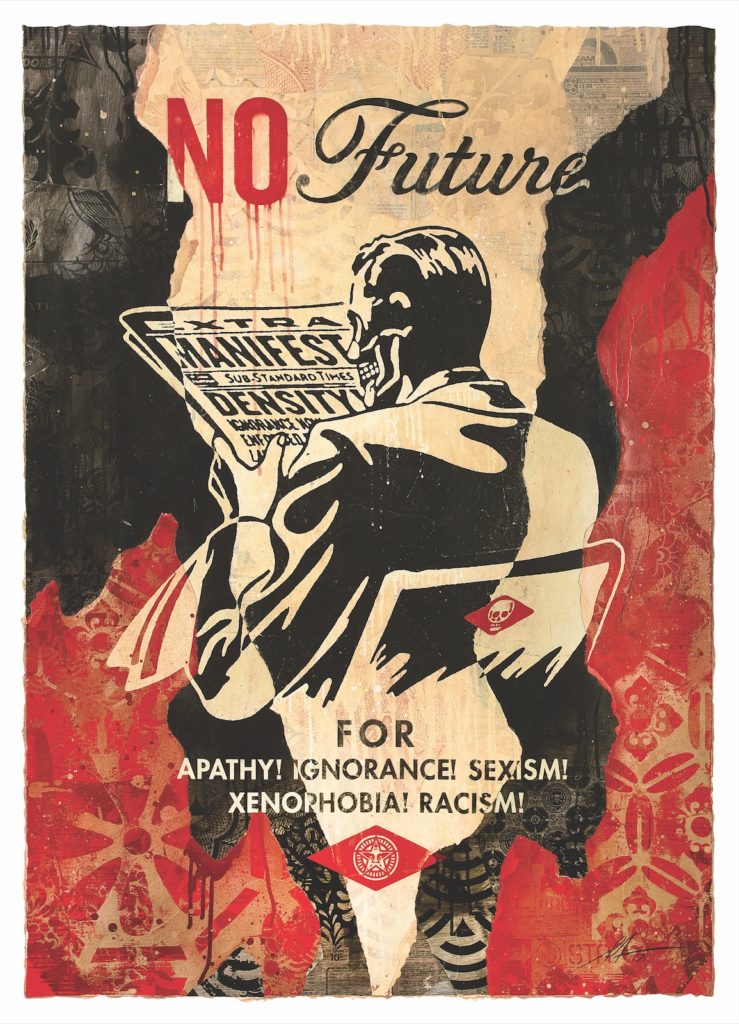

“No Future,” 2016

The Obama poster would vault Fairey to international fame, and become one of the most celebrated and recognizable images in the history of American politics. As the visual centerpiece in chief campaign strategist David Axelrod’s orchestrations for Obama, Fairey’s creation would ultimately prove to be the catalyst for an overarching paradigm shift taking place in the business of political branding. He hadn’t exactly invented the wheel—campaign posters and slogans have been commonplace in the United States since John Quincy Adams debuted them in 1824—but with the advent of social media outlets and viral systems of communication, an elephantine sense of urgency surrounding the value of image-related content had gained momentum in Washington, for better or worse.

“The visual is important, but possibly only as a facet of brand awareness,” says Fairey. “Unfortunately, brand awareness and popularity seem to move the needle more than strong ideas and integrity.” The other side of the aisle took firm notice of the trend, and eventually succumbed to the uber-brand in Donald Trump. The Republican Party’s outmoded ideology allowed for no more viable path to the presidency than that of a former reality TV star whose preternatural flare for overhyped business deals and incendiary outcry would triumph by the power of name recognition and consistent (if disgusting) self-imagery.

“I have a lot of problems with the two-party system because it reduces and oversimplifies things; there definitely aren’t enough choices,” says Fairey. “I’d love to see other parties rise to viability. What I’m hoping is that the dark days we’re experiencing politically are as troubling as they should be for a huge number of people to see this as a wakeup call.” Despite the rising red tide, Fairey maintains a certain optimism with regard to the potential for modern branding with positive impact.

“We the People,” 2017

“I think it’s possible to use imagery in ways that are very positive and not superficial,” he says. It’s a trait at the heart of Damaged. “My propaganda campaign—which is designed to encourage people to question propaganda—is something that I do with a sensitivity to the visual language of our culture, but also a desire to encourage people to consume with discretion and basically question everything. When you look at how shrewd a lot of advertising, marketing, and political propaganda is, it would be foolish not to try to push back with some of the same techniques, but with a sense of moral responsibility.”

One year removed from Obama’s first inauguration, the dynamism of Fairey’s career would be further sharpened by the release of Exit Through the Gift Shop, a film by the subversive street artist—and Fairey contemporary—Banksy. The film blurs lines between documentary and satire, and left critics scrabbling in vain at perceived factual inconsistencies, raising many questions surrounding the relationships of persona to identity and art to commerce. The story is told through the lens of Thierry Guetta, a.k.a. Mr. Brainwash, a French expatriate street artist living in Los Angeles, and it’s allegedly compiled from thousands of hours of footage dating back to the late ’80s and directed by Banksy himself. As one of the primary subjects of Guetta’s footage, Fairey—along with his exploits—serves as an instrumental narrative element in the film.

“I think it’s possible to use imagery in ways that are very positive and not superficial.”

In the years since the release of Exit Through the Gift Shop, the film’s themes have become increasingly nebulous—street artists now routinely make compromises in the name of business and seek manifold revenue streams in order to claim a beggar’s portion of the return on value represented by their work. Though his own star was made long ago, Fairey can relate to the inherent conundrum of what it means to be an artist in the digital age, when access is paramount and all is disposable.

“It’s hard to find a balance between not being too in people’s face versus seeming out of step with our culture’s metabolism, where people are constantly looking for new images, messages, et cetera,” he says. “I’m working hard to balance quantity and quality, but I don’t think I’m exactly ubiquitous compared to a lot of things in pop culture.”

Though he concedes that young artists must learn to worship the dual-faced god, as it were, to maintain their sanity and survive such a volatile sociocultural landscape, he still believes in the power of the image to come out of nowhere and transmute that landscape in such a way that unearths and cultivates the virtues of autonomy and transparency. This was Fairey’s ultimate aim all those years ago when he finally managed to tag the building at Houston and Broadway. But the fight remains ongoing and the world is always changing. Whether in the physical or digital realm, political or economic sector, and everywhere in between, we will never run short of structures to overcome. Keep raging, keep hustling, keep on questioning everything.

“I think the barriers between fine art, commercial art, and creative product are eroding quickly,” he says. “The powers that be in the elite world of fine art might not like it and may work very hard to maintain the gatekeeping mechanisms of that world, but I think a lot of people have already scaled the walls. I’ve scaled a few walls.” FL

This article appears in FLOOD 7. You can download or purchase the magazine here.