From the time Patty Schemel was born, her parents were in Alcoholics Anonymous, hosting meetings in their home forty-five miles north of Seattle. Schemel likens the experience to being brought up religious. In the opening of her recent memoir, Hit So Hard—a follow-up of sorts to the 2011 documentary of the same name—she writes, “our guidelines for living were based on the Twelve Steps.” While living under their roof, Schemel tried a lot of new things that would end up shaping the rest of her life. She kissed a girl. She joined the high school marching band and got her first drum kit. And she got drunk.

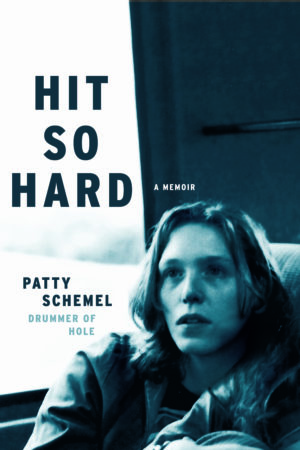

Schemel’s powerful drumming was introduced to international audiences when she joined Hole prior to the recording of their breakthrough 1994 album Live Through This, after her close friend Kurt Cobain sang her praises to his wife, Courtney Love. By this point, Schemel was a full-blown addict, being picked up drunk at bars by her girlfriends and shooting heroin, a drug with a fierce grip on many artists and musicians in Seattle. Also in 1994, Hole bassist Kristen Pfaff died of a heroin overdose—two months after Cobain’s suicide—and Schemel’s downward spiral continued. She was featured on the cover of Celebrity Skin, Hole’s third album, but she’d been kicked out of the band by the time it was released; her drumming on it was re-recorded by a session musician.

Today, Schemel has been sober for nearly thirteen years. She spends her time playing drums in the band Upset, volunteering, and raising her daughter alongside her wife in Los Angeles. We talked to Schemel about Hit So Hard, in which she’s a de facto historian of 1990s Seattle, a notably visible gay female musician, and a clear-eyed observer of the hell she’s been through—all things she carries proudly.

There’s a point in the book where you talk about how shooting up helped you see a little more clearly. Obviously, a lot of people use drugs and alcohol for the opposite reason: to escape from where they are. I’ve never heard it described the way you talk about it, like putting glasses on and being able to see. Can you elaborate on that?

It was more like a new discovery, like there’s another way to be, another way to feel. The best way I can describe it is that before I discovered drums, I felt awkward and not part of the world. Just different. And gay. And then I discovered drums, and that put me into my body, like I’d landed finally. And then I discovered drugs and alcohol, and that did that for me, too. I wanted that all the time. That just put me together. Maybe it’s more of an outbreath, like, “Oh, OK.”

What is it like to meet someone like Courtney Love for the first time? What was your first impression of her?

There’s an energy to her that can fill up the whole room. She’s the one that’s steering what’s happening and your exchanges. We fit together well musically and personally because I don’t mind that force in the room. It sounds like I’m really taking on a new age-y vibe, but I’d take all of that energy and push it through myself and let it go out. But you need to have boundaries with people in your life who are that way. On one hand, they’re amazing artists. On the other hand, it can be dangerous. It’s intense.

There’s an energy to her that can fill up the whole room. She’s the one that’s steering what’s happening and your exchanges. We fit together well musically and personally because I don’t mind that force in the room. It sounds like I’m really taking on a new age-y vibe, but I’d take all of that energy and push it through myself and let it go out. But you need to have boundaries with people in your life who are that way. On one hand, they’re amazing artists. On the other hand, it can be dangerous. It’s intense.

I’m kind of sensitive. At the time, in my early twenties, I didn’t have any boundaries really. So that just created more uneasiness inside me. It was that dysfunctional-family vibe, where I was always making sure everybody was OK in my band, the way I used to in my own family. It goes deep! My girlfriend, whoever it was at the time, was one way to escape people. Drugs [were] my number one. That’s the way that I would calm my own self and let go of that anger.

So there was this double whammy when Kurt died and then Kristen died right after. You talk about how, after that, you were determined to make your own rehab stick. Do you feel like that loss was a turning point for a lot of people in Seattle? Was it a wake-up call, or did it just plummet everyone further into whatever hell they were living through?

Kurt, for me, was my wake-up call, but I’d say it was a pause. I went to rehab and then I came out, and then I was just back to using pretty quickly while we were on the road for Live Through This. But Kristen being right after Kurt, and her death being sort of overshadowed by O.J. Simpson in the Bronco all over the news… It made some weird perspective for me. I felt like this was such an important person in my life—totally overshadowed by Kurt’s death, overshadowed by current events—and then feeling like there should be so much more to this. With Kurt’s death, it was like JFK. [Kristen] was more of a personal, private grieving.

That was a tough time. I was so shut down. For me, as an addict, nothing really stopped me from using. No events, nothing anyone said to me. That was just somebody opening their mouth saying words that didn’t mean anything to me. I would go to rehab thirty-seven times because my band asked me to, or management asked me to, or it was a requirement, or I was arrested or court-ordered. There was nothing that worked for me. It was the cliché that you have to lose it all. And that’s the story in the book—losing all of it—and then what’s it taken, what’s happened, why it clicked for me on March 1, 2005. And why it did was because I had nothing. I was just blank.

We get to the point in the book—and in your life—where you’re homeless and having sex with men for drugs. The way you describe it is so matter-of-fact that, as a reader, I had to stop myself and be like, “Wait a minute, holy shit.” But you describe it as what you had to do to get through the day, so it’s easy to miss the severity of the situation. What was it like for you to relive that while you were writing?

The way that I dealt with a lot of the hard stuff was to make jokes, look at the funny parts of it. That experience, when I’m thinking about it and we were writing about it, was difficult. But it was so matter-of-fact in writing because that’s just what I did to get money in my hands so I could get high. There were all kinds of different hustles that I worked through to get money for drugs. Stealing, whatever. I walked away from the days of writing about that with such heaviness. I was still thinking that I’d maybe worked out some of that past stuff already, but then in writing the book, it comes back up again. And these are things that I’m putting down in a book, on a page.

“That’s a heavy blow, to have these dreams, and then you get there and you’re like, ‘I don’t feel like I thought I would.’ Still searching for the thing. It’s scary.”

And I think about the community I live in. I love my friends, but my daughter goes to school. I think about revealing some of those things about myself. I hear those things every day in meetings. I hear those things plus a billion other things that we do. So I guess I’m exposing this world, on one hand, and some people are shocked. And other people are like, “Eh, well, I know that!” I just, in some way, thought people knew more about drugs and alcohol and recovery, or what the disease is. It seems so prevalent now with all the oxycontin and opioids. All these people from all kinds of classes—the mom in Virginia Beach saying, “What’s going on?” All of a sudden this whole world is dumped onto them.

Your book was also a good reminder that heroin in the ’90s was so big that people were using phrases like “heroin chic”—which is such a weird thing. You mention Scott Weiland and ending up at the same dealer’s house, and of course he passed away a couple of years ago. You end the book talking about Chris Cornell, who just died, and it’s a good reminder that famous people aren’t just addicts when they’re young and hot. They don’t age out of it. This is something that people deal with for the entirety of their lives.

You carry it with you. Becoming famous and achieving dreams doesn’t fix you. And that’s a heavy blow, to have these dreams, and then you get there and you’re like, “I don’t feel like I thought I would.” Still searching for the thing. It’s scary. Like with Chris Cornell, it’s…it’s sad. I don’t know. It’s sad that that was the decision. And I have no judgment. I understand totally why, and I don’t know his personal thoughts, but I can relate to what I think he might have thought.

photo by Darcy Hemley

You’ve been sober for twelve years, and I don’t know if this is a reasonable question to ask, but do you become addicted to something else? Do you focus your energy on family or playing music? Does that become an addiction?

I’ve heard people get clean and then all of a sudden they’re like, “I’m a marathon runner!” And I wish that was my case, but it’s not. I wish. I can get so addicted to anything. I really have to keep it in check. Like food. I feel the same kind of feelings—not to the extreme physical extent, but it activates the same receptors in my brain when I eat a piece of chocolate cake, so there’s that. I try to balance stuff out. Drums have been my place where I can reel it all in and get balanced and right-sized, when I sit and play. But whenever I get stressed—like, I’m doing all this press for the book, and there’s a lot of uneasy stuff, and someone’s going to ask me some bullshit questions—whenever I start to feel uneasy, all of a sudden I’m like, “God, I’m starving.” Like, “Is there a snack area here at this radio station? Do you guys have, like, a bag of M&M’s I might enjoy?” [Laughs.]

Did you have a goal for the book? Was it for you, or did you want it to be a cautionary tale—or was it a mixture of both?

“It was important to talk about that time in Seattle as a piece of history.”

I wanted to tell my story with the recovery throughline. I wanted to talk about my story as an addict, but I also wanted to talk about being a female musician and playing an instrument that not a lot of women do, and the way it was. It was important for me to be visible and to tell the story. That’s what I have. Also, I like to read books about music. I like music docs. And it was important to talk about that time in Seattle as a piece of history. People ask about it all the time. When I volunteer at Rock [n’ Roll] Camp for Girls, I have that experience to talk about and to share with other girls. The book was about sharing that and telling my story. I wanted my story to be told, and I wanted to tell it.

I feel like men don’t really understand what it’s like to look onstage and see someone who looks like them, because they’ve grown up with it. It’s not a weird thing for them. But to see women being so visible and playing instruments—it still gets me. It’s really powerful.

Yeah, when I was a kid, there weren’t a lot of women drummers. Then punk rock came along, and there were a lot more women playing in bands in punk rock, I thought. Also, I didn’t see any women that were gay that came out, and I needed to hear that and I needed to see it. That’s why I came out in Rolling Stone in 1995. I didn’t make a conscious decision to do that, but it just happened, and then I was sharing my life with people. And I hope that kid in Kansas who feels freaky because he or she is gay feels better. FL