It looks like the kind of living room you might see in a downtown Los Angeles condo: tasteful mid-century furnishings, framed vintage sci-fi posters (2001, Blade Runner), a copy of Led Zeppelin I ready for action on the turntable. The only things that look out of place are the thick stalks of grass swaying gently on an end table.

I run my hand across the grass and hear a series of plaintive tones, like a stringed instrument gently picking out all the notes in a chord. I look down and see more grass coming up out of the carpet, then some kind of pitcher plant that seems to extend its undulating mouth toward my outstretched hand, like a pet expecting a treat. It responds to my touch with a sonorous sigh. As I turn my head, more ethereal plants come into view. I sit down on the floor and experiment with touching them, enjoying how the soothing ambient music all around me changes with each moment of contact.

The plants are illusions, of course—inhabitants of a virtual world called Tónandi, created by the Icelandic band Sigur Rós in collaboration with Magic Leap, a tech startup. The living room is sort of an illusion, too—not the home of a hipster into Kubrick and classic rock, but a product demo space at Magic Leap’s offices in Culver City, not far from the LA tech hub of Silicon Beach. Magic Leap calls their technology “mixed reality,” and it’s important to show that, unlike virtual reality, which blocks out the real world, MR coexists with one’s natural environment. Through a surprisingly lightweight set of MR goggles, I can still see the pattern of the carpet beneath the waving grass and sighing pitcher plants, and hear Mike Tucker, creative and technical co-lead of the Tónandi project, as he explains the behavior of his creations.

“See how they’re all sort of perking up to look at you?” he asks, referring to the virtual plants. “It was important to give a sense of life to everything.”

As multimedia art projects go, Tónandi is pretty amazing stuff—an interactive audiovisual experience that makes you feel like you’re inside Sigur Rós’s otherworldly music, communing with it in ways far beyond what could be achieved with any existing augmented reality app or VR headset. But it’s also proof of concept for a technology that has made Magic Leap one of the most well-funded startups in history. Since its founding in 2011, the company has raised over $2 billion. Google is a major investor, as is Andreessen Horowitz, the venture capital firm co-founded by the man behind early web browser Netscape, who knows a thing or two about bleeding-edge technologies. A rapturous 2016 cover story on Magic Leap in WIRED declared, “This is what disruption on a vast scale looks like.”

Sigur Rós became early participants in mixed reality at the behest of Magic Leap’s founder, Rony Abovitz, a longtime fan of the band. Five years ago, he invited them to his company’s headquarters in Florida, where they viewed an early prototype. “The first glasses were humongous,” says Jónsi, the group’s frontman. “Like a really big machine [that] you put your head in.” Later versions were only slightly less cumbersome; one on display in Culver City looks like a deep-sea diving helmet attached to a thicket of cables.

Jónsi

Sitting alone on the patio of a craft beer bar, not far from where he and his partner Alex Somers now live in LA part-time, Jónsi looks a bit like a mixed-reality projection himself, an elfin presence in an otherwise prosaic setting. He greets me by singing along, in his trademark falsetto, to the main riff of Europe’s “The Final Countdown,” which is blasting from the bar’s speakers. Sigur Rós’s hyper-emotive, avant-garde music can sometimes feel shrouded in seriousness, but there’s a playful, mischievous air about Jónsi that clearly informed Tónandi’s aesthetic.

We’re soon joined on the patio by Sarah Hopper, the band’s creative director, who’s been integral in keeping the Tónandi experience true to the band’s vision. British, with close-cropped blonde hair, Hopper projects a no-nonsense attitude that stands in contrast to Jónsi’s more laid-back demeanor. Despite LA’s sweltering weather, she sips hot green tea while Jónsi and I nurse cold-brew coffees.

“I think what Magic Leap thought initially was, ‘Wouldn’t it be cool if you had Sigur Rós playing in your living room?’” she says of their early meetings. “But for Sigur Rós, that idea would be like, ‘Why would we ever do that?’ So it was kind of tricky at first grappling with the concept of what it would become.”

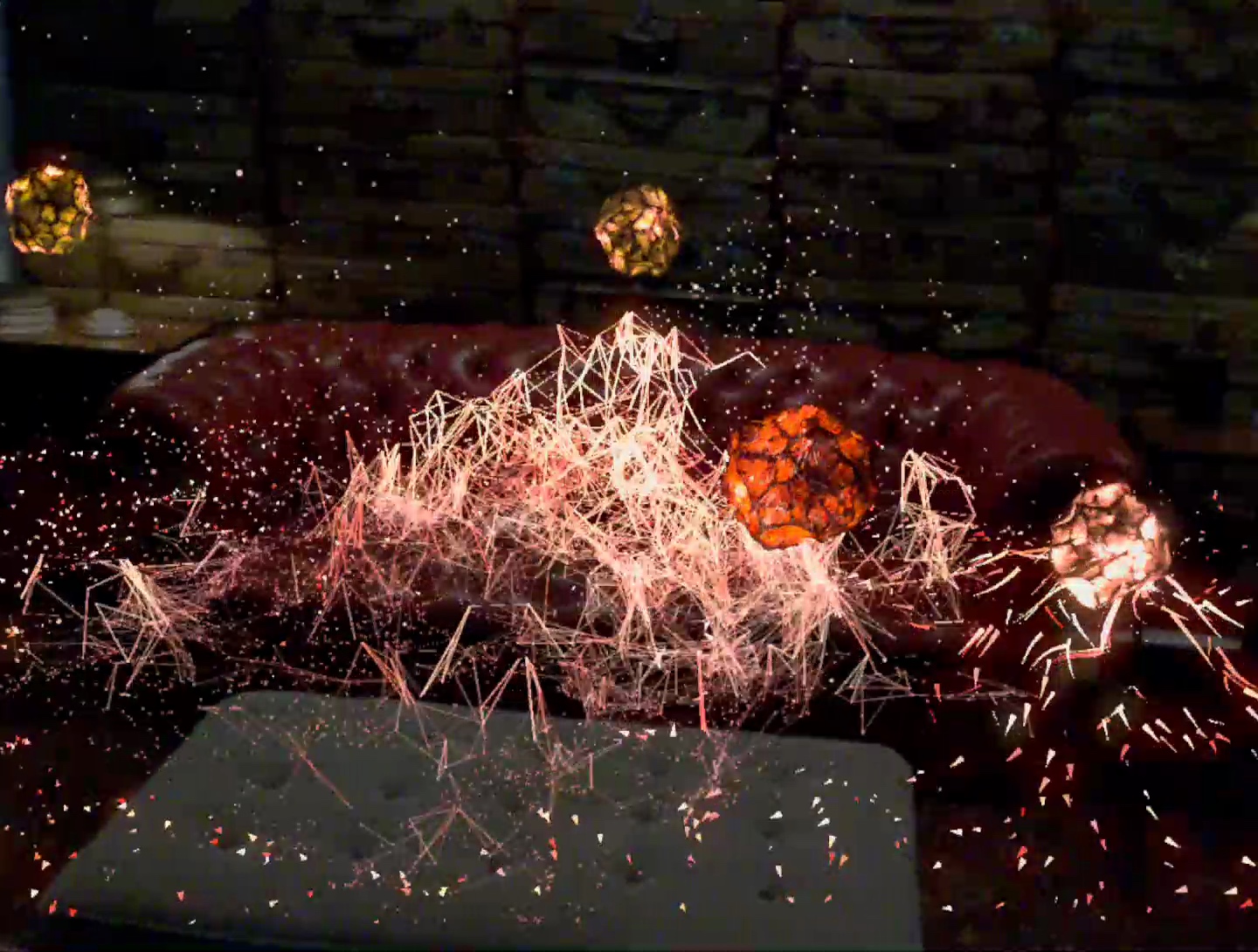

After Magic Leap presented some cartoonish creature designs that still “didn’t feel very Sigur Rós,” Hopper and the band finally hit on what became Tónandi’s core concept: representing “the DNA of sound” in a visual way. Sometimes those representations can be quite literal; in one moment, a Lissajous pattern—a classic visualization of a sound wave—appears floating in space, accompanied by a matching tone. Others are more abstract, like a flock of small, butterfly-like creatures that accompany a heavily processed sample of Jónsi’s vocals.

After Magic Leap presented some cartoonish creature designs that still “didn’t feel very Sigur Rós,” Hopper and the band finally hit on what became Tónandi’s core concept: representing “the DNA of sound” in a visual way. Sometimes those representations can be quite literal; in one moment, a Lissajous pattern—a classic visualization of a sound wave—appears floating in space, accompanied by a matching tone. Others are more abstract, like a flock of small, butterfly-like creatures that accompany a heavily processed sample of Jónsi’s vocals.

“Tónandi is so immersive that you actually are forced to listen in a different way.” — Sarah Hopper

“What’s interesting about this one is it’s all spatialized so you get this swarming effect,” says Stephen Mangiat, Mike Tucker’s project co-lead, as the butterflies (or bats, as Mangiat prefers to describe them) swoop around the room. And it’s true; thanks to another Magic Leap innovation called spatial audio, and a set of tiny speakers strategically placed around the headband that holds my MR goggles in place, I feel as though the sound of the bat/butterfly swarm is tracking around me in three dimensions. This, the Magic Leap team says, is another important advancement over previous virtual reality technology, which typically only presents sound in stereo or in surround sound that’s been “upmixed” from a stereo original.

“I’ve done surround mixes where it’s like, ‘OK, take the album and convert it up.’ And that’s how it’s been for a long time,” says Paul Corley, Sigur Rós’s music director and sound engineer, who worked on the music for Tónandi. “One of the exciting things for me on this—and I hope more people get a chance to do it—is to start writing knowing that it’s gonna be for spatial audio. I think that will change people’s writing process in a really interesting way.” Tónandi, he says, now contains over a thousand spatialized sounds, all sampled from Sigur Rós’s music and all responsive to the user’s movements, in effect allowing you to “compose” new music each time you go through the experience.

In this regard, Tónandi is a high-tech cousin to Liminal, a series of sound bath events that Jónsi, Corley, and Somers announced earlier this year. At Liminal, the audience lies on the floor, letting pulsating lights and ambient music wash over them. In Tónandi, the user becomes submerged in mixed reality—at one point quite literally, as a rainstorm fills the room with water and the sounds become murky and subaquatic. Both experiences present music in a way that demands your undivided attention—a somewhat radical notion in the era of streaming and playlists, when music is more and more often presented as background accompaniment to some other activity. “[Tónandi] is so immersive that you actually are forced to listen in a different way,” says Hopper.

Jónsi

Though Magic Leap’s technology has advanced by, well, leaps, it’s still a work in progress. During my first trip through the demo, a calibration issue causes many of the MR objects to appear only partially, as though I’m viewing them through an aperture not much larger than a carton of cigarettes. (Before my second run, we change out the nose bridge on the goggles and run an app that tests my field of vision, which greatly improves the experience.) The translucent quality of Tónandi’s inhabitants, though it fits the shimmering quality of the music, was dictated by bandwidth as much as aesthetics. “Because the sound is the very important thing in this experience, the visual side of it had to be dealt with in a way that didn’t take too much processing power,” Hopper explains.

Despite these limitations, the experience can still be breathtaking. The way the MR goggles manage to map the physical space is especially impressive. Objects really do appear to sprout up from the floor and out from the walls, and when a beam of light pans across a bookcase, its edges trace the spine of every book with startling accuracy. Despite the ephemerality, Tónandi seems tactile enough that it fools my other senses; blue shards of ice seem cool to the touch, and when a trail of energy suddenly shoots forth from my fingertips, I instinctively recoil my hand to control its intensity. (“That one’s really fun to do with two hands,” says Corley. “You kind of feel like Gandalf.”)

“This could, in the end, basically replace everything: phones, TVs, computers.” — Jónsi

Even after I take off the goggles, Tónandi’s effect on my senses persists. Birthday cupcakes laid out for the project’s executive producer, Magic Leap senior director Rebecca Barkin, look like a 3D-animated mirage, vibrating with color in an otherwise stark white conference room. I become acutely aware of the way our footsteps reverberate off the industrial space’s concrete floors into its high, wooden rafters. After time spent in mixed reality, actual reality feels heightened.

Tónandi represents just one small sliver of mixed reality’s potential. Though Magic Leap remains secretive about its various projects—Jónsi jokes that even he has no idea what else they’re working on—other demos they’ve shared with the media have included everything from games and 3D-scale models to virtual assistants and simulated computer monitors. Early on in Tónandi’s development, Jónsi says, Abovitz told him, “This could, in the end, basically replace everything: phones, TVs, computers.”

Given all that potential, and the $2 billion in venture capital, it may seem quixotic that when Magic Leap launched its “Creator Edition” on Wednesday—a limited-release set of previews and demos that will be the first time the company has shared its technology with a wider audience—an avant-garde rock band from Iceland will play such an integral role. “I really respect Rony. It’s brave that this is one of the first things he’s putting out,” Jónsi acknowledges. “Because it’s not about making money, really.”

Given all that potential, and the $2 billion in venture capital, it may seem quixotic that when Magic Leap launched its “Creator Edition” on Wednesday—a limited-release set of previews and demos that will be the first time the company has shared its technology with a wider audience—an avant-garde rock band from Iceland will play such an integral role. “I really respect Rony. It’s brave that this is one of the first things he’s putting out,” Jónsi acknowledges. “Because it’s not about making money, really.”

Then again, given the experimental nature of what Magic Leap is developing, it makes sense for them to align themselves with an experimental band. And Sigur Rós’s involvement has rewarded the company’s designers and developers in other, less tangible ways.

“One of the things that was exciting for us yesterday was seeing Jónsi in there composing with the different elements,” Barkin tells me after my own trip through Tónandi. “Just to watch him play with his own sounds in a different way was really cool.” FL