Though traditional rock music has accumulated infinite subgenres since it was popularized in the late ’50s, no band has personified—and later epitomized—the label of “anti-rock” as well as Silver Jews. The term “anti-rock” in and of itself is contrarian in a way that slickly encapsulates the whole genesis of the band. And David Berman, the group’s heart and soul, as well as its only concrete member since its formation in 1989, never expected to be known as a musician.

For Berman, it was poetry first, music second. His music has been labeled as a Pavement side-project from the beginning, and with Pavement members Stephen Malkmus, Bob Nastanovich, and Steve West all contributing to a handful of Jews albums, it’s clear why that happened. But the Silver Jews have always been Berman, and Berman alone.

By the end of their run, Pavement had become a caricature of themselves. Though the weirdos-with-guitars ethos of ’90s rock had cashed in on white male fragility, there was still something absurdly macho about the rock music of much of that era, and Pavement gleefully played into that. Nu metal and rap-rock were ruling the airwaves, but when Silver Jews released American Water in 1998, Berman dismembered the façade of misogyny-fueled guitar rock with something vulnerable, sincere, and self-deprecating. Where Malkmus had simply mocked contemporary rock, Berman sought to destroy it.

Some might say the ’90s didn’t really end until 9/11, and if that’s the case, American Water eloquently captures the end of the pre-9/11 era in America. The idea of indie rock, by that point, was completely superficial, something marketable. Veering away from the indie rock of the ’80s, the careless and uncorrupted creative flow of outsiders started being seen as a valuable commodity. And then, just like that, post-9/11, the leather-strapped “rock star” was back in fashion, as seen in the rise of The Strokes, The White Stripes, and Yeah Yeah Yeahs—safer bets in a paranoid and perturbed America.

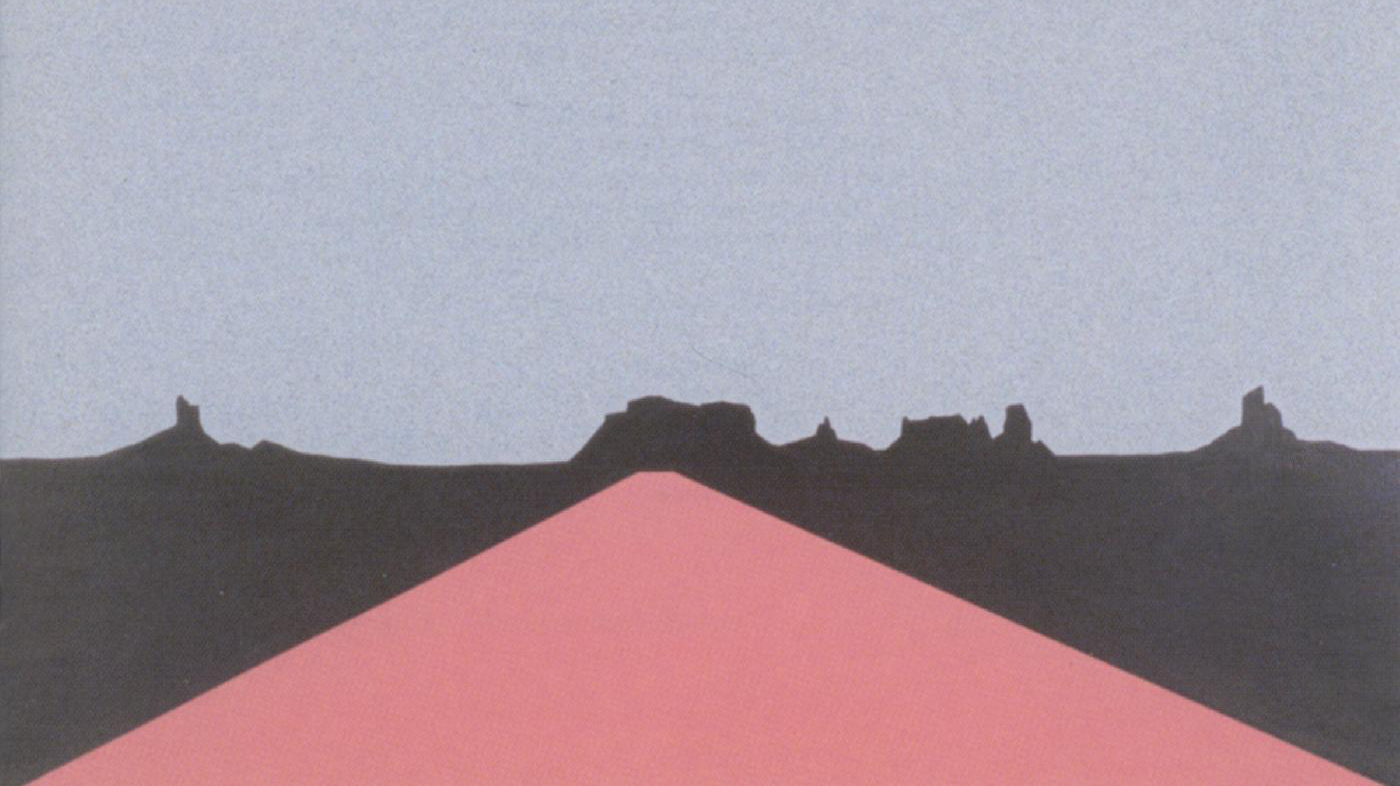

Looking back on that epoch of post-9/11 bands pulling from hard rock influences such as T. Rex, New York Dolls, and Thin Lizzy, it’s interesting to hear how committed Silver Jews were to old country records. Berman’s idyllic rockstar presentation wasn’t slathered in leather and glitter, but rather in work boots and worn-in denim, sipping draft beer in the back corner of a shit-hole bar. On “We Are Real,” Berman famously drones, “All my favorite singers couldn’t sing.” He was right. Berman idolized the songwriting of Haggard, Kristofferson, Van Zandt—unbeatable songwriters, highly beatable crooners. American Water represents the underdog in America, the forgotten small towns littered throughout the Rust Belt.

Where Stephen Malkmus had simply mocked contemporary rock, David Berman sought to destroy it.

Berman’s rural sensibility bleeds with an innate and primal quality on American Water—the rolling, tumbling bass line of “Smith & Jones Forever” erupts in every step it takes; the restless, dueling guitars of “Night Society” speak a language of anxiety you or I could only dream of articulating so well; the watered-down boogie of “Federal Dust” embodies an inner insomniac, prancing around in the early hours of the morning. This is a personal record, a dirty secret you share with Berman. That secret isn’t so much a brief conversation as it is an extended dialogue, a cluster of stories you may have shared with a friend over one too many whiskeys: about puppies from Kentucky, suburban kids with biblical names, marching children’s crusades, midnight executions.

American Water is an album so conceptually vague that regardless of your demographic or location—or era—it has a place for you. The humanity and bleak metaphors found deep within its trenches make for something singular—a sonorous language of stark, plainspoken quips. The observations Berman spews read like American history at the turn of the millennium, where passion and reason quickly turn into paranoia and political psychosis. There hasn’t been an indie record—or rock record, for that matter—like it since. FL