“Cohen was never taken very seriously as a poet,” reads a wildly misguided review of Leonard Cohen’s final published work, The Flame: Poems, Notebooks, Lyrics, Drawings, in last week’s New York Times. “He wasn’t much of a singer, either; but the gravelly renderings of his lyrics gradually attracted a mass audience.” This incendiary hot take has faced understandable backlash on Twitter, and its writer, contemporary poetry critic William Logan, has been accused of holding a specific grudge against Leonard—as the review stinks oddly of vitriol.

Logan seems uninterested in exploring the mass appeal of Cohen, tossing aside his illustrious career and legions of adoring fans (I’d estimate Leonard taught roughly one million men how to love a woman, and introduced two million women to the kind of love they craved). To critique any artist intelligently, though the eventual analysis may be scathing, there should be a modicum of respect; if not for Cohen himself, then for his scores of fans, who cannot all be fools.

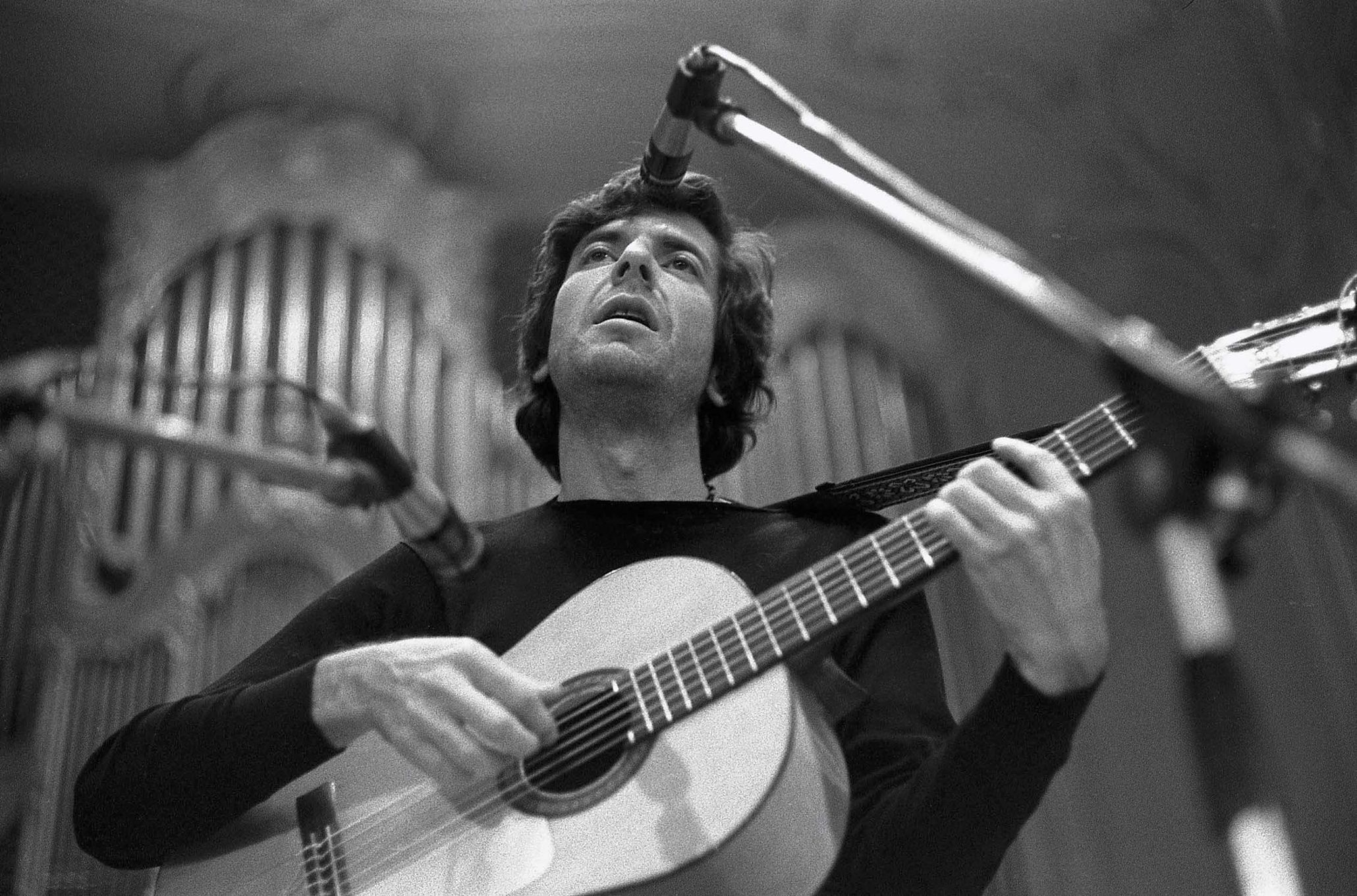

Logan’s hypothesis is that Cohen was a sucky poet, but his words somehow worked as lyrics accompanied by a baritone purr. Or, to quote Logan warmly and exactly: “As poems these squibs are worthless; as lyrics, even sung in that lizardy groan, they often moved millions.” To see Cohen’s sensuous, panther-black sound distilled down to a “lizardy groan” is fascinating stuff, but more important to note is that Logan fails to realize poetry isn’t only diction and syntax on a flat page—the way Leonard Cohen sings, his lustrous, growly cadence, is poetry too.

I’ve collected some of Cohen’s best lyrics that, when read alone, make for lovely poetry—but when sung by our gentleman scholar, make for transcendent ruminations on love, death, and everything in between.

1) “One of Us Cannot Be Wrong,” from Songs of Leonard Cohen (1967)

Cohen’s voice was lightest and reediest in his early days, and what made his stuff irresistible to women then has remained consistent through the decades: Leonard worshipped the lovers he wrote about. He craved spiritual enlightenment, but that frequently came in the form of carnal pleasure. This song is no exception, spinning a tale of several men (including a doctor, saint, eskimo, and Cohen himself) who’ve gone mad over some woman. By the narrative’s end, Cohen’s wailing la-la’s fade to screams of torment. This verse looks corny written out, but sounds infinitely sexy when sung.

I showed my heart to the doctor

He said I’d just have to quit

Then he wrote himself a prescription, and your name was mentioned in it

Then he locked himself in a library shelf with the details of our honeymoon

And I hear from the nurse that he’s gotten much worse and his practice is all in a ruin

2) “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye,” from Songs of Leonard Cohen (1967)

Another tender song from the more-innocent boy Cohen of the ’60s, this particular melancholic verse provides a wise descriptor of love, vowing that while a separation might be imminent and circumstances shifty, the affection between two people will never be lost. I thought about using it as my senior yearbook quote to express how I felt about leaving my high school friends, but went for something jokey instead. Sincerity is scary.

I’m not looking for another as I wander in my time

Walk me to the corner, our steps will always rhyme

You know my love goes with you as your love stays with me

It’s just the way it changes, like the shoreline and the sea

3) “Bird on a Wire,” from Songs from a Room (1969)

Kris Kristofferson has said he wants this song’s opening lines inscribed on his tombstone—a high compliment, to be sure. Here, Cohen confesses his faults and then begs for forgiveness. In one verse he paraphrases the opposing sides of our human condition using just four lines: the first two hold gratitude for all that we have, and the second two admit to a ceaseless, nagging desire to have more, be better. Note the way his voice breaks with longing while holding “crutch” and “door.”

I saw a beggar leaning on his wooden crutch

He said to me, “You must not ask for so much.”

And a pretty woman leaning in her darkened door

She cried to me, “Hey, why not ask for more?”

4) “Democracy,” from The Future (1992)

Cohen is Canadian by birth, but became an American citizen by career necessity (living in LA up until his death). “Democracy” is an ode to his imperfect adopted country—he laments its faults, but also believes in its improvement. In this verse he professes his bipartisanship, nails TV addiction (the “hopeless little screen” could just as easily refer to Apple products in 2019) and our penchant for littering, and simultaneously promises to stay and hope and grow here.

I’m sentimental, if you know what I mean

I love the country but I can’t stand the scene

And I’m neither left or right

I’m just staying home tonight

Getting lost in that hopeless little screen

But I’m stubborn as those garbage bags

That time cannot decay

I’m junk but I’m still holding up

This little wild bouquet

Democracy is coming to the U.S.A

5) “Anthem,” from The Future, (1992)

This makes for an obvious choice, but the chorus of Cohen’s “Anthem” is so simple and triumphant I couldn’t help but include it. At first blush the verse looks thin, even inconsequential, but when Cohen croaks out these phrases of eternal comfort, slowly and deliberately, as a chorus of angel voices tremble behind him, it’s another story. His voice plummets deep into the earth with, “They’ve summoned up a thundercloud / And they’re going to hear from me,” and I feel certain I’d go to war for his cause, whatever it is.

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack, a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in

6) “Closing Time,” from The Future, (1992)

In the bridge of this slidey-seesaw party tune, Cohen both cops to his own superficiality—he only loved a chick because she was hot (typical)—and exonerates himself, because she’s shallow, too. Brutal, but incisive.

I loved you for your beauty

But that doesn’t make a fool of me:

You were in it for your beauty, too

7) “Going Home,” from Old Ideas (2012)

Cohen was probably arrogant, like most famous men (or anyone with a rabid fanbase), but he was also entirely capable of humility, apology, and prostrating himself. In the practically-whispered, meta lines opening one of his last albums, Leonard refers to himself as “a lazy bastard living in a suit,” alluding to an ongoing struggle (impostor syndrome?) with his own insignificance; though he spouts wisdom to millions, Leonard knows he is but a mere mortal, “a brief elaboration of a tune.” Of course, he’s more than that to a great many people—but the self-deprecation is appreciated.

I’d love to speak with Leonard

He’s a sportsman and a shepherd

He’s a lazy bastard

Living in a suit

But he does say what I tell him

Even though it isn’t welcome

He just doesn’t have the freedom

To refuse

He will speak these words of wisdom

Like a sage, a man of vision

Though he knows he’s really nothing

But the brief elaboration of a tune

8) “You Want it Darker,” from You Want it Darker (2016)

Cohen’s final album was released a little over two weeks before his death in 2016, and it was a lot less horny than his previous efforts—perhaps because he was eighty-two, and even the most libidinous libidos slow down eventually. “You Want it Darker” reads like a prayer, with overt religious overtones and an implied audience of God himself: Leonard suspects he will die soon, and is resigned to the swiftness with which life’s breath is snuffed whenever the holy Being wills it. When he chants “hineni hineni,” a Hebrew phrase of devotion (“I’m ready, my lord”), his voice is barely a rumble—not a storm brewing, but rather one fading into the distance, receding over the horizon line, gray and somber and mighty.

If you are the dealer, I’m out of the game

If you are the healer, it means I’m broken and lame

If thine is the glory then mine must be the shame

You want it darker

We kill the flame