We are in the midst of a renaissance in psychedelic-assisted therapy and research. This new wave comes after many decades of repression and scientific radio silence as our society has been subject to an onslaught of misinformation around psychoactive plants. Almost five decades after defining many psychedelics, including psilocybin, as Class 1 substances, the cultural and scientific winds are shifting as more and more rational voices come out of the psychedelic closet.

This gradual sea change in collective opinion is spurred partly by the psychedelic research over the last two decades occurring at institutions like Johns Hopkins, New York University, and Imperial College London. These studies all explore the effectiveness of psilocybin for a host of issues including anxiety, depression, addiction, end of life care, and more. Recently, the FDA granted psilocybin a “breakthrough therapy” for treatment resistant depression. This research is the tip of a scientific iceberg, and psilocybin is reaching a tipping point in scientific and societal acceptance as a viable and acceptable therapeutic tool.

The data is profound in its probability of success, with many studies resulting in well over 70 percent positive results: for long-term effectiveness (sometimes lasting years), low toxicity (less than coffee), and non-addictive character (cue the pharmaceutical industry shudder). Psilocybin is not without its dangers and faults, but in 2016 the Global Drug Survey rated it safest drug in the world used recreationally.

But what if, even amidst the generally positive early research results, we’ve had a major blind spot and are missing out on the full potential of psilocybin-assisted therapy in particular? Can we build a repeatable protocol and psychedelic experience based off the tools of past anthropological use but tailor-made for our modern psyche?

It is wise to review psychoactive plant use by indigenous cultures around the world to mine clues for best methods and practice, while accepting that methodologies developed in cultures and environments far removed from the space-age lifestyle of iPhones and air travel may not translate to the needs of the modern psyche. Yet the ancient technology of ceremony itself still proves effective and demands respect; it offers numerous insights into how to create a proper mindset and physical setting for a successful psychedelic journey. It would be foolish to ignore our ancestors’ countless generations of “research” as they developed forms of ritual to best engage with these substances. Yet weaving all of this into a contemporary therapeutic setting requires mindfulness to cultural appropriation.

One way to artfully bridge the gap of including ritual and ceremony into a therapeutic and/or research setting is through music. Early studies recognized the central role that music plays in the psychedelic experience, such as Mendel Kaelen, a Beckley Foundation Research Fellow at Imperial College, who found that the interaction between psilocybin and music caused a profound effect on the subjective experience and promoted positive therapeutic results. In many ways, music is the ceremony. This is mirrored in indigenous shamanic ceremony, as many use sound and song as a primary vehicle of ritual.

My work as a composer, musician, and teacher began ten years ago with my project East Forest. The music was created specifically for the psilocybin mushroom experience—music that guides the listener inside and actively helps facilitate a transpersonal journey. This is done by blending ancient indigenous sound techniques, like repetitive drums and looped percussive phrasing, to help entrain the brain, alongside modern day sound healing ideas, such as alternative tunings, with software like Ableton Live and wearable biofeedback technology. This soundscape is specifically designed to ground the listener in an instrumentation that helps create a familiarity recognizable to the western ear while igniting a primal felt sense of the numinous. It is an inviting sonic landscape that evades a singular genre while aiming for a liminal feeling space—floating in between emotional polarities and allowing for one’s consciousness to expand.

The interaction between psilocybin and music caused a profound effect on the subjective experience and promoted positive therapeutic results.

From the beginning of East Forest, the electro-acoustic ambient music was created for ceremonial healing practices. In private circles, my music was the central guide for groups of people moving into deep introspective states that lasted from four to six hours. Step by step, I built a protocol for the journey using musical techniques and tools I learned from firsthand experience in indigenous ceremonies, as well as contemporary sound healing technologies. The success of a circle was gauged via the barometer of how powerfully positive, safe, and effective the experience was for the participants. I saw the work as a kind of laboratory where we tested the mind and heart. Again and again, I witnessed people deeply unfolding into their psyches, returning a few hours later with a level of self-healing and understanding typically only accessed through years of psychotherapy. This is seen in the psilocybin studies at Johns Hopkins where individuals rated their experience in the same top five spiritual events of their life alongside the birth of a child or death of a parent. When asked, these feelings of depth and resonance remained with many of the research participants for many years.

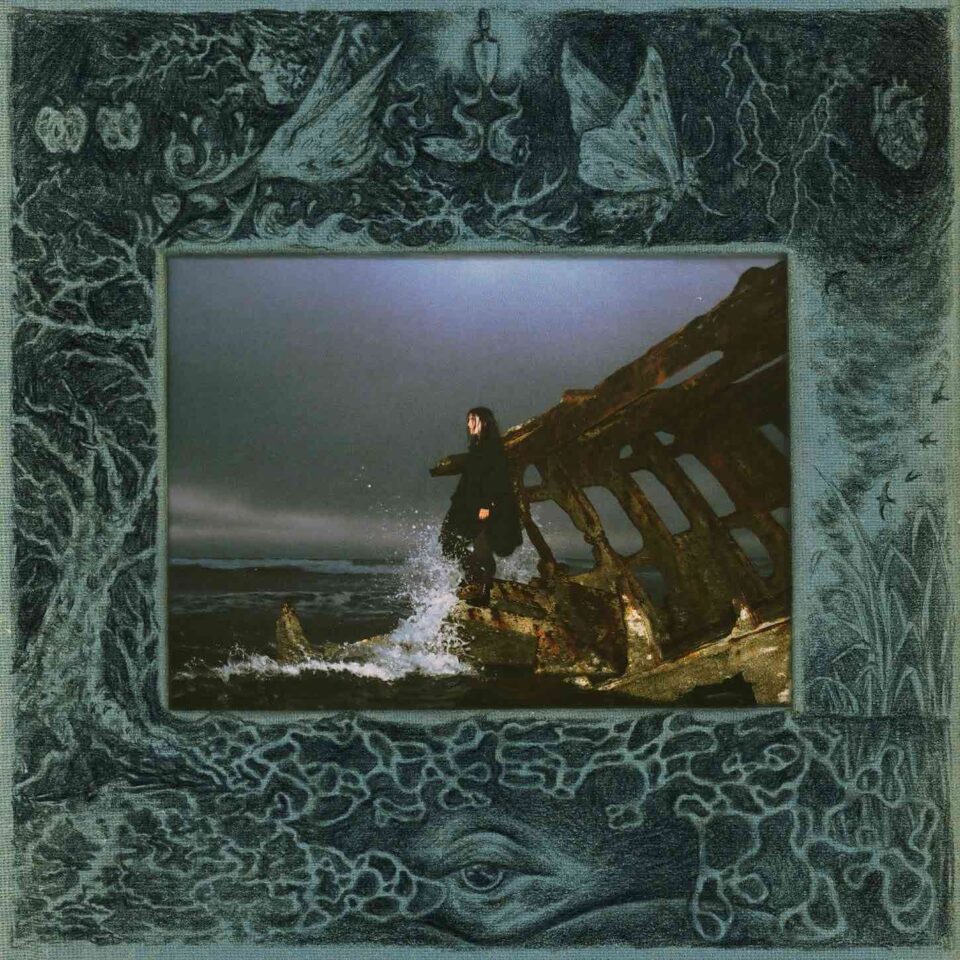

For myself, after ten years of making music in the psychedelic shadows, I am finally bringing to the public light this protocol. This offering is a definitive musical tool to help the burgeoning field of psychedelic-assisted therapy blossom into even fuller potential. My album Music for Mushrooms is a five-hour, fully connected journey designed to musically guide a group or individual through an entire psilocybin experience, start to finish.

My motivation to publicly offer a musical work for psilocybin is also inspired by my current work with the spiritual teacher Ram Dass. Ram Dass and I have been collaborating on a joint album that features new recordings from the acclaimed teacher overlayed with new East Forest music. The whole project is a fourteen-track album, releasing across four “chapters” throughout 2019. Having the opportunity to travel to Ram Dass’ home and spend time with him in his study, positing questions to him about the problems we face today, and then being able to hear his answers from the wise place of eighty-eight rich years on the planet, was a profound experience to say the least. Ram Dass is arguably a founding psychedelic grandfather of our country. He, along with Timothy Leary, pioneered many of the earliest psilocybin studies when he was a professor at Harvard in the ’60s. For the album, I asked Ram Dass about the new momentum of psychedelic therapy, where he sees it going, and what kind of role it has played in his life. After a comic pause he answered, “Psilocybin…is my friend.” He credits it with setting him on his spiritual path. Some sixty years later, he is still a leading voice in American spirituality, and by many respects more popular, and needed, than ever.

In creating Music for Mushrooms, I hope to offer an alternative to the music playlists created by Imperial College and Johns Hopkins, which I feel miss the mark. My album is designed specifically for psilocybin and the music is composed during ceremonies. Its compositional shape guides, and is guided by, the arch of the experience. The music of the current psilocybin public research therapy playlists is an amalgamation of tracks by different composers—none of the songs were originally intended for psilocybin. Further, most of these songs are comparatively short. The songs of Music for Mushrooms are all extended connected tracks—some up to thirty minutes—with a slow and gentle growth, an organic progression that aligns with the waves of feeling and experience in the psychedelic journey. This progressive unfolding allows the journeyer to enter into sonic and emotional worlds gradually, to explore the psychic depths with peaceful transitions that allow for time to integrate the experience before moving into the following song or space.

Additionally, Music for Mushrooms integrates original nature field recordings throughout the composition. It is well known by experienced mushroom users that nature provides a special solace in combination with the active ingredient psilocybin. Field recordings of “that which is still wild” provide a soothing synthesis of nature into what might otherwise be a staid and sterile therapeutic setting. Sounds of nature can unlock memories, calm our senses, and contain a texture that welcomes our most ancient self home—whether it be via a chorus of crickets or a gentle mountain breeze.

This album aims to forge a new shamanic path—one that is birthed of our musical tools and the technology of our time while also honoring and inspired by the rich history of our human relationship to psychedelic plants and fungi.

As mentioned, Music for Mushrooms was recorded and improvised live, while guiding a group in ceremony. In this way, it contains the “energy of the medicine.” It was birthed in the moment, reacting in real time to the ebb and flow of a collective journey. Plant-based medicine ceremony historically used music as its primary vehicle and that music was, of course, live. This is not an encumberment of a pre-1900s lack of electricity or prerecorded music, but rather of the relationship of the guide/singer/shaman using tone and frequency as a central element in crafting the set and setting of the ceremony. Needless to say, playing and creating music in real time inside a ceremonial setting is a unique stage from which to record music.

The new album is intentionally conducive to the psychedelic experience in a variety of additional ways, like avoiding lyrical content so as not to spark the language centers of the brain. The record employs falsetto vocalizations throughout, utilizing a non-lyrical language composed primarily of improvised vowels. The voice becomes more of an instrument, communicating via melody and vocal texture more than words. With the live looping technology, I employ harmonies and a full choir can develop.

Most people have never experienced psilocybin inside a ceremonial setting. My album aims to create a new sonic tradition, one that all of our ears can understand.

The sound of Music for Mushrooms couches itself in western melody and an instrumentation familiar to the western ear such as pianos, harmonicas, and Fender Rhodes keyboards. Comparatively, traditional icaros, the centuries-old sacred songs of the Amazonian Ayahuasca ceremonies, can have stark shakers and likely unfamiliar Quechua language. No doubt icaros are a form of highly effective spiritual technology, and are an integral element of a traditional Ayahuasca ceremony. But psilocybin doesn’t have a musical equivalent to the icaros of South America. The recent proliferation of underground Ayahuasca ceremonies all across the world has maintained and integrated into the experience the element of ceremony. Ayahuasca isn’t used recreationally. Amazingly, ceremony has never detached itself from this drug. Psilocybin, on the other hand—while music is in the drug’s ceremonial cultural past—has remained almost entirely recreational for westerners. There is no known specific heritage of music with psilocybin. Most people have never experienced psilocybin inside a ceremonial setting. My album aims to create a new sonic tradition, one that all of our ears can understand.

While listening to Music for Mushrooms, your brain won’t need to work overtime to understand the musical lexicon presented, because the album uses pianos and chord progressions primarily rooted in contemporary music. At the same time, the record does utilise indigenous musical elements like native flutes, shakers, and Tibetan bowls. These ancient native instruments can be employed effectively in select musical moments to connect the dots of our human psychedelic history into a contemporary shamanic listening experience. It serves as an ancestral bridge that honors old ceremonial technology and integrates it with a modern instrumentation.

All of these techniques and methods calm the body and mind and set the stage for a safe and positive psychedelic experience. The results of the recent studies are promising, and I am hopeful we are entering into a golden age of psychedelic research. It is our birthright to explore our consciousness, and in understanding ourselves, we in turn understand one another.

What is being called for in our time is a fresh shamanic lineage—one born out of our needs and this time. We are being asked to step forward, to build on the lessons of our ancestors while trailblazing a shamanic future that ties together the pinnacles of history. Music is a necessary ingredient in this transformation.

I’ve always intuitively felt that the solutions our world needs will not come from the top down. Rather, the answers we’ve been looking for will come from the inside out. By exploring our interior landscape to heal our traumas, to root out shame, to learn to love ourselves, we empower our ability to make positive changes that echo out into our lives and the world around us.

Ram Dass likes to say that we are here as souls to learn, to walk one another home—and thankfully we have more tools now than ever to help us along the way. FL