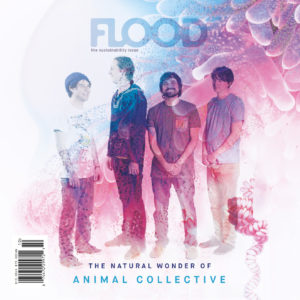

This article appears in FLOOD 10. You can purchase the magazine here.

“What is this?” That was the exact sensation I had during Animal Collective’s performance last year at the David Lynch–organized Festival of Disruption at New York City’s Brooklyn Steel venue. The experimental pop group have built a two-decade career out of subverting expectations by way of simply following their creative arrow, whether or not their audience is prepared for it; during much of the 2000s, they’d tour behind a recently released record with a set largely comprised of unreleased material—often earmarked for their next album—in unstructured, embryonic form.

In the years following the release of 2009’s mega-hyped landmark Merriweather Post Pavilion, AnCo adopted a more traditional live approach of stocking their setlists with material from their most recent release, along with slightly reworked catalog cuts depending on their gear setup. It was a bit of a surprise, then, that the Festival of Disruption set was comprised almost entirely of unreleased material, with lovely and murky underwater footage projected behind the band on a giant screen.

Even more surprising was the group’s lineup: every member accounted for except Panda Bear (Noah Lennox), apparently sitting out a major AnCo performance for the first time in years. As Avey Tare (Dave Portner), Geologist (Brian Weitz), and Deakin (Josh Dibb) crafted amorphous, watery-sounding tones and drones onstage, the audience seemed to exist in between states of confoundedness and disinterest, chattering loudly to the point where the crowd noise almost matched the decibel level of what was taking place onstage. Whether you were a longtime fan or a casual observer, the whole scene undoubtedly caused you to ask: What are these guys up to?

AnCo / photo by Atiba Jefferson

The answer would come several months later in the form of Tangerine Reef, an audiovisual collaboration with Miami-based art-science duo Coral Morphologic that also counted as Animal Collective’s eleventh studio album. The first full-length in the geographically scattered group’s existence not to feature Lennox, released just two years after the earthy proto-punk of 2016’s Painting With, the record came as a surprise to fans—who had come to expect a lengthy period of time between AnCo albums in the 2010s—as well as the band’s label, Domino. “It caught them off guard,” Dibb recalls. “They didn’t know we were in the studio. We were like, ‘We just made this. We’re pretty psyched on it—would you be into putting it out?’”

Even at their most accessible, Animal Collective have long been known as a challenging band, leavening bursts of puckered melody with massive washes of noise, and crashing through choruses with aural dissonance and vocal freak-outs. But even by those standards, Tangerine Reef still stands as a particularly difficult record in their catalog, with little in the way of conventional song structure beyond Portner’s uneasy vocals floating in the reflective sonic ether.

“Musically, it’s some of the most obscure stuff we’ve done in a while. It’s a record about the environment, and the visuals lend themselves to that.” — Avey Tare (Dave Portner)

Similar to The Flaming Lips’ notorious 1997 quadruple-CD album Zaireeka—which can only be heard properly through four stereos playing all four discs simultaneously—consuming Tangerine Reef the way its creators intended presents its own difficulties. Portner states that the album’s impact is most greatly felt as a true audiovisual experience, accompanied by the film that Coral Morphologic’s Colin Foord and J.D. McKay put together to match its aqueous vibes. “Musically, it’s some of the most obscure stuff we’ve done in a while,” Portner explains, adding that his lyrics penned for the record were purely improvisational. “It’s a record about the environment, and the visuals lend themselves to that.”

Beyond its high-concept construction, Tangerine Reef is also borne out of the band’s personal history, despite representing their latest left-turn in a career explicitly charted with no straight-line traversals in mind. Their passions—both in terms of creatively embracing the spontaneous and exuding a thoughtfulness about the future of our planet—are reflected through the album more than on any other AnCo release from this decade; Tangerine Reef also represents the full realization of a group dynamic the quartet have steadily cultivated since childhood. “The past two and a half years have been more of a realization of what we set out to do than anything previous,” Lennox exclaims. “It’s what we wanted to do when we were a lot younger.”

The four members of Animal Collective aren’t necessarily unusual, but their personalities are unusually attuned to creating the kind of energy balance required to sustain a creative partnership. While Dibb and Weitz are moderately gregarious and forthcoming in conversation, the other two members are what Lennox affectionately terms “shy guys”—warm personalities essentially cocooned in a way that takes some shared familiarity to help them open up to new people. “Brian and Josh are always the friends that Noah and I look to to handle certain situations and communicate with people,” Portner explains. “I’ve worked very hard to become more outward, and Noah has changed a ton, but we’re just people who are quiet.”

Given such an even personality split, it’s surprising—but, considering AnCo’s predilection for pairing off in various permutations throughout their career, oddly fitting—that the way the quartet initially came together betrayed these direct pairings. Lennox and Dibb became friends while attending grade school in Baltimore, bonding over video games and an early interest in music. “Noah’s just somebody who I gravitated toward—he had a certain vibe that made sense to me,” Dibb recalls while mentioning that both providentially played cello in school. “Music was another way that we connected.”

After Weitz moved from Philadelphia to Baltimore, he befriended Portner in high school over a shared affinity for the Grateful Dead, Pavement, and mind-expanding substances like mushrooms and LSD. “At that age, having similar interests in music and drugs is really important,” Weitz says while recalling their points of connection. “If you’re going through your formative years with a like-minded person, it can reflect more basic personality traits.” The friendship came at a crucial time for Portner, who was considering a school transfer after struggling with the social aspect of education: “I felt like I wasn’t fitting in,” he notes. “I remember calling up Brian for the first time and asking him to go to the mall with me. It took a lot of courage, because I wasn’t a very social person.”

“We definitely caught the tail end of the not-digital age, which isn’t really the way things work anymore. The importance of owning a physical copy of something that would change my life…it’s really hard to have that experience with music anymore.”

— Deakin (Josh Dibb)

The pairs of friends first coalesced midway through high school while dabbling in music via the joys of home recording, as well as by forming the pre-AnCo outfit Automine, featuring all the members sans Lennox. They put out one release—the Paddington Band 7” in 1995—before disbanding. College found the quartet splintering off again, with Lennox and Dibb attending schools in Boston and the other two turning to New York City for higher education; around this time, their separate experiments with home recording started bearing fruit in the form of Lennox’s 1999 self-titled debut as Panda Bear and the recording of Spirit They’ve Gone, Spirit They’ve Vanished, the 2000 LP widely considered AnCo’s debut despite its roots as a solo effort from Portner.

After the Boston boys and Portner decided to drop out of school, all four came together under the same roof with the purpose of focusing on music more than ever before. If you’ve paid attention to indie on any level during the last twenty years, you’re well aware of what happened next: Throughout the 2000s, AnCo amassed a growing critical and cult fanbase with every release, starting with the psych-folk bonhomie of 2004’s Sung Tongs and leading up to the big, bassy, galactic dance music of Merriweather.

Still from Tangerine Reef

AnCo’s rise within indie’s amorphous confines—a steady increase in popularity which extended far beyond the avant circles of outré-NYC peers like Black Dice and Excepter—to this day remains unmatched in this century of popular music. The idea of a band as weird-sounding as them reaching such a level of success feels unreplicable in today’s musical climate, a singular sensation that Dibb credits to AnCo’s rise in a pre-streaming era where physical media still reigned supreme: “We definitely caught the tail end of the not-digital age, which isn’t really the way things work anymore,” he explains. “The importance of owning a physical copy of something that would change my life…it’s really hard to have that experience with music anymore.”

For a group of guys with experimental-leaning tastes whose idea of “making it” was having their music featured on the shelves of since-shuttered Manhattan music mecca Other Music, the critical and commercial interest in AnCo’s sound (Sung Tongs’ jaunty “Sweet Road” was featured in a Crayola commercial) was a relative shock tempered by uncertainties about the future taking place behind the scenes. Lennox himself admits that, from the years 2002 to 2009—a time period that practically encompasses the band’s initial rise—he was unsure of AnCo’s longevity. “The band kind of fell apart a number of times,” Portner states, recalling an emotionally charged letter Lennox wrote to him at “a crucial point in our friendship. I remember a big falling-out in our practice space with Noah throwing drumsticks—that was a point where I was like, ‘Oh, it’s over.’”

AnCo + Coral Morphologic / photo by Jacob Boll, courtesy of Festival of Disruption

Further complicating matters, Lennox decided to move to his current home base in Lisbon in 2004 to be with his now-wife and mother of his two children, fashion designer Fernanda Pereira. “I felt a lot of anxiety about him coming back to make Feels, because he just left and we didn’t speak a lot about what the future of the band would be,” Portner admits. But the first step in what would result in AnCo’s overall geographical scattering—Dibb still lives in their native Baltimore and Weitz in nearby Washington, D.C., with Portner decamping to North Carolina after an LA stint—had the opposite effect, strengthening the band’s collective bond through the necessity of personal space.

“Because we were so open to just doing whatever, it was crucial to be like, ‘It’s okay for Noah to go away, because it’s actually better for us all,’” Portner explains. Beyond distance making the collaborative heart grow fonder, spreading out also meant slowing down—a necessity following the always-be-touring schedule AnCo found themselves in at the height of Merriweather’s promo cycle. “The fact that we all live in different places is a benefit,” Dibb explains while reflecting on the personal growth the band’s achieved since their early-2000s cohabitational days. “There was a certain amount of grating on each other’s personal space, and everybody has their own ways that they feel comfortable in their home life.”

“If people aren’t given the room they need, it doesn’t result in anything good,” Weitz continues, while discussing the staggered informal schedule—AnCo albums and tours are spaced out by years of downtime for the quartet to pursue solo projects and other personal passions—that the band’s adopted over the last decade. “It helped us navigate solo careers in a healthy way.”

Lennox describes AnCo’s current platonic ideal of creation as “a lot of projects and various groupings of us doing things,” which is precisely how Tangerine Reef came about. The project carried deep roots in the band’s history, dating back to Weitz’s studying environmental science and policy at Columbia University, as well as his work at the Biosphere 2 research facility in Arizona. “I got scuba certified the first chance I could,” he enthuses, and the deep-diving bug bit Dibb later in his teens. The two have continued to strike out on far-flung scuba-diving trips throughout adulthood.

While Dibb and Weitz were discovering what lies beneath the ocean’s shimmering surface, Coral Morphologic’s Colin Foord—who had fallen in with “art and music kids” while studying marine biology at the University of Miami—was discovering Animal Collective’s music, citing a 2006 drive from Miami to one of their concerts in Asheville (“The longest drive I’ve ever done to see a band”) as a flashpoint for his interest in their work. “I started out as a fan,” Foord recalls, and after a screening of AnCo’s 2010 experimental film ODDSAC in Miami, he and J.D. McKay approached Dibb and Weitz with a DVD of their visually tactile, reef-exploring work.

“We didn’t have to have a long conversation about what the environmental message was. Somebody who doesn’t scuba dive or know anything about these creatures could watch it and have their minds blown.” — Geologist (Brian Weitz)

A quick friendship was struck between the two artistic pairs, and soon Weitz and Dibb were heading out on dives with Foord and staying with the pair when passing through Miami. In the summer of 2011, they invited Foord out on a planned excursion at the coral islands Turks and Caicos, but the trip was quickly dashed by the arrival of the destructive Hurricane Irene, resulting in the would-be divers holing up in a hotel room with a bottle of rum and nowhere to go. Out of this temporary isolation and the locale they were stranded in, a creative partnership was born: “We didn’t have to have a long conversation about what the environmental message was,” Weitz explained on the discussion of artistic common ground that led to Tangerine Reef. “Somebody who doesn’t scuba dive or know anything about these creatures could watch it and have their minds blown.”

Work on Tangerine Reef wouldn’t begin until nearly six years later, when Coral Morphologic was awarded a grant for a large-scale project by the Miami-hosted Borscht Film Festival in 2017. “They pitched a live video-music collaboration with us,” Dibb remembers. “They’d put together footage in their lab, and we’d come down and write some music.” Portner joined in the writing process, while Lennox sat out due to scheduling concerns stemming from his Lisbon residency; the intention was to record the Borscht performance for future release à la AnCo’s 2012 EP Transverse Temporal Gyrus, effectively a live recording of a 2010 art installation the band erected at NYC’s Guggenheim Museum—a plan that was scrapped after crowd noise overpowered the music itself on the final recording.

Geologist + Deakin / photo by Drew Weiner

After decamping to a Baltimore studio to record the material for posterity over the course of a few days, AnCo decided to release Tangerine Reef properly via the album and audiovisual formats that it currently exists in. “We initially recorded it just for the memory—to give Colin and J.D. a screener version,” Dibb explains. “We didn’t know it was something we even wanted to release until we were done.” Beyond the environmental implications of the release itself, Tangerine Reef carries a personal connection for Portner, the only non-diver of the group’s iteration that participated in the recording.

“I’m a very watery person, and reflections are a big thing for me,” he ruminates while contemplating the future of our oceans. “It’s weird to imagine murky, dead water that you can’t see the reflection of the sky in anymore—to imagine a generation of kids who don’t get to enjoy the ocean.” Although Lennox sat out Tangerine Reef’s gestation, his concern for our dying planet’s ecological future is no different—but it’s tempered with hope, too. “I’m not just battening down the hatches and thinking everything’s going to end, you know?” he asks into the cosmic void. “I try to stay optimistic with my kids, but it’s tough. It seems like they’re getting screwed by previous generations. But without hope, what’s the point?”

If the distant global future seems uncertain, AnCo’s flurry of current and future activity is full of possibilities. Earlier this year, two solo albums arrived from the camp: Panda Bear’s spacey, elemental Buoys and the iridescent pop of Avey Tare’s Cows on Hourglass Pond. And there’s plenty more to look forward to: along with a U.S. tour in the fall that includes a headlining slot at the far-out Desert Daze festival in Joshua Tree, AnCo are starting to get into the headspace of following up Tangerine Reef—slowly, but surely. “It’s underway,” Lennox claims tentatively, qualifying that he’s “gotten in trouble” in the past for suggesting that the band was farther along in the studio than publicly perceived. “I’ve probably written more songs in the second half of last year than I’ve written in my life. I’m hoping we’ll get together this summer, but we’ll see.”

If it sounds like there’s no real rush to get to work, that’s because working at their own pace has become crucial to AnCo’s present-day stability, as well as to ensuring their future as friends and bandmates. “The more we’ve evolved, the more we’ve gotten to have our own space and be our own people,” Dibb enthuses. “We’re very different in many ways. It’s important to have that separation so that when we do come together, we’re just really psyched to see each other. Going in the studio or on tour is like a…” He pauses, and laughs. “Damn, I don’t want to use this word—brocation. Shit. But that’s what it is.” FL