To be a woman is to be constantly observed; being an actor only magnifies that sensation. To be Jessica Lange, a now-iconic presence on screen and stage, is to be observed, molded into a man’s vision of a twenty-something sexpot (giant ape palm optional), and measured against that image—for better or worse—for the next forty years. To be a photographer, though, is to be in control of the narrative, become the watcher instead of the watched. It’s independent work; there are no cogs in well-oiled Hollywood machines that need to be relied upon to create something. It’s just you and your camera, and the story you want to tell.

Lange, a two-time Academy Award winner, is not the first actor to take up residency behind the lens in her spare time—Jeff Bridges, Brad Pitt, and Dennis Hopper, among others, have all published work over the years—but Lange’s craft is no mere hobby. Her photos share a devastatingly lonely quality, often capturing haunting visions of landscapes and people that hinge on the precipice of disappearance. So well do they carry their own weight, it’s a shame that society—which often must categorize women as one thing in order to take them seriously—tends to regard Lange not as both an actor and photographer, but as an actor who happens to also take photos.

Highway 61, Lange’s fourth published collection, proves the strength of her gaze on its own, away from the shadow of her stardom. Through a monograph released this October via PowerHouse Books and an exhibition showing from November 21 through January 18 at New York’s Howard Greenberg Gallery, Highway 61 takes the viewer on a road trip through middle America, documenting the historic road from its origin at the Canadian border through its end in downtown New Orleans in eighty-four gritty tritone photographs.

“I have a long history with Highway 61,” Lange, now seventy, writes in the book’s afterword. “I was born in a small town along that road in Northern Minnesota, as were my parents and sisters. Most of my family—grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins—were born, married, and died in towns on that same stretch.” Lange very well could have followed suit, had she not itched to leave town at eighteen, stumbled into a photography class her freshman year at the University of Minnesota where she fell in love with a photographer, and quit school to follow him on a bohemian adventure through Paris, San Francisco, and downtown New York at the dawn of the 1970s.

“I have a long history with Highway 61,” Lange, now seventy, writes in the book’s afterword. “I was born in a small town along that road in Northern Minnesota, as were my parents and sisters. Most of my family—grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins—were born, married, and died in towns on that same stretch.” Lange very well could have followed suit, had she not itched to leave town at eighteen, stumbled into a photography class her freshman year at the University of Minnesota where she fell in love with a photographer, and quit school to follow him on a bohemian adventure through Paris, San Francisco, and downtown New York at the dawn of the 1970s.

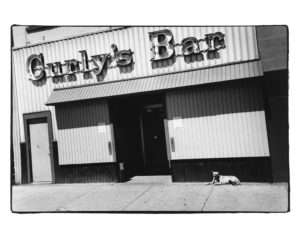

To view life along the highway through Lange’s lens is to view a ghost of what America once was and may never be again; all abandoned factories, boarded up Main Street storefronts, and empty beer halls where only memories occupy stool seats.

In the ensuing years, Lange established herself as one of her generation’s most formidable actresses in films like The Postman Always Rings Twice, Frances, and Tootsie. It wasn’t until the early ’90s that Lange began taking photos in earnest—incidentally, around the same time Hollywood began to nudge her and her peers into the “wife, mother, or district attorney” stage of their careers—when then-partner Sam Shepard gifted her a Leica. Shortly after, Lange returned home to Minnesota to raise her children, camera in hand to capture it all.

It’s this comfortable familiarity with the land, this push and pull between past and present, that informs Lange’s Highway 61. Bob Dylan’s vision of the highway may be the definitive one in contemporary pop culture—and Lange cites its influence as the first album she bought at age sixteen—but her take on the place is quieter, more desolate, and far sadder. Hers is a vision of all the small town trappings many women resent in their ambitious youths but learn to appreciate, and perhaps return to, decades later.

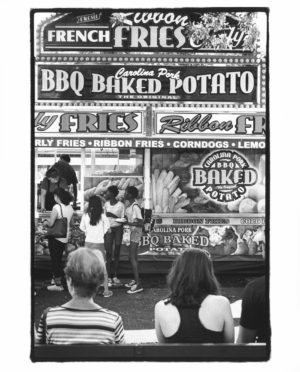

To view life along the highway through Lange’s lens is to view a ghost of what America once was and may never be again; all abandoned factories, boarded up Main Street storefronts, and empty beer halls where only memories occupy stool seats. Images of what remains and what is clung to—greasy spoon diners, animated state fairs and town parades, roadside farm stands—often feel like evidence that will be looked at in the near future for proof that something entirely gone did, indeed, once exist.

Lange has spoken often of her lifelong loneliness; it bleeds into her work, especially in Highway 61, at times almost unbearably so. Stare a little too long and you might begin to feel the photos’ melancholy seep into the marrow of your bones, a quality Lange acknowledged in discussion with art director Sam Shahid at a recent appearance in New York. “Not that anybody wants it,” she laughed, “but you can share in my loneliness.” It might not be what the viewer wants, but perhaps it’s what she wants; two lonely people being lonely together are better than one.

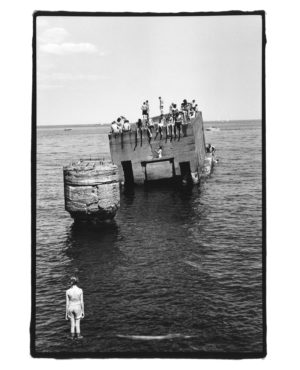

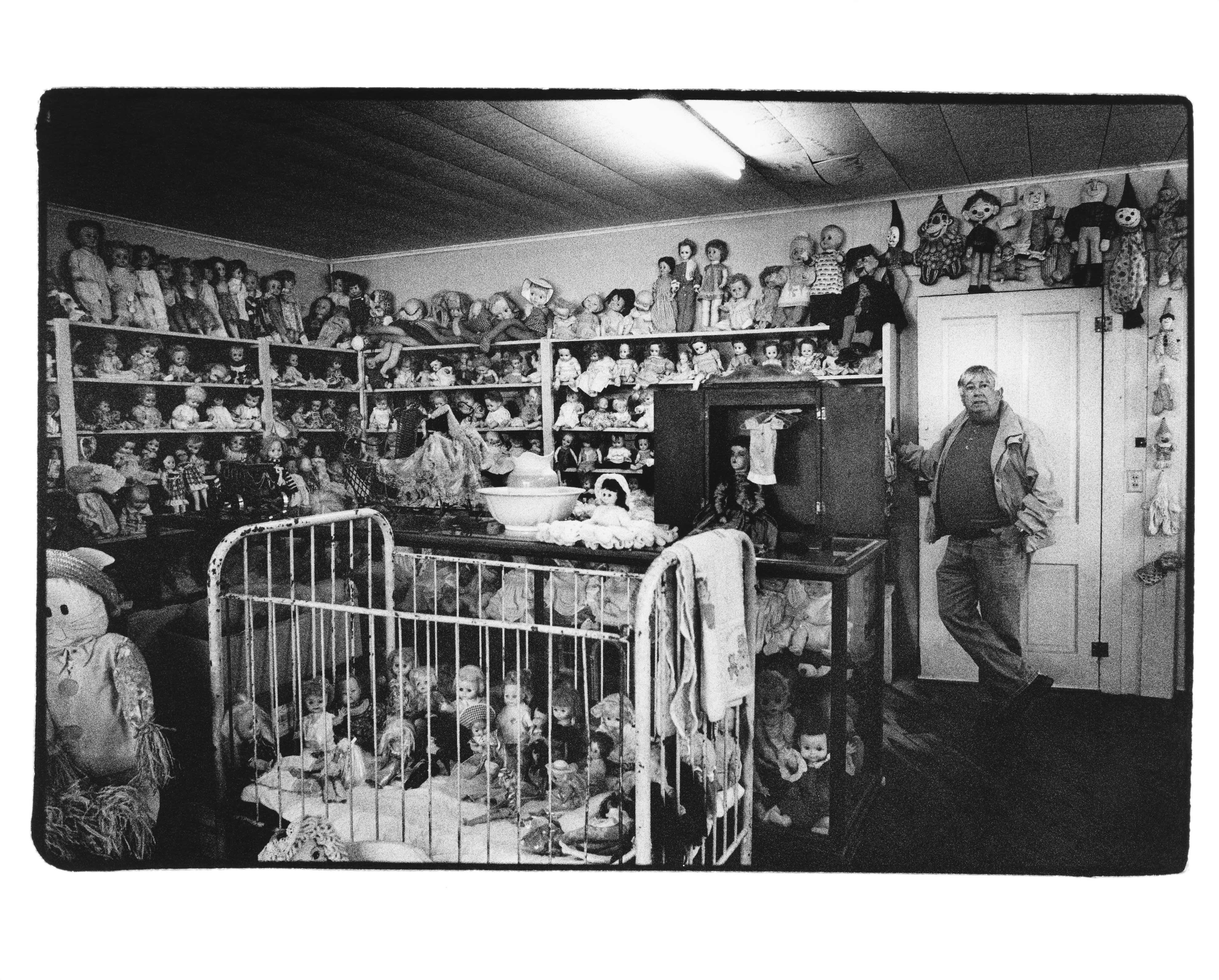

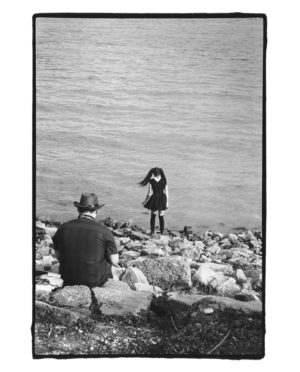

This sense of shared solitude is a current throughout her work, the camera gravitating toward loners, seemingly connected to them by a siren call. A young girl stands on a lake’s shore, watching her peers crowd a concrete structure jutting out of the water; an aging cowboy contemplates a county fair machine game; a grey-haired man eats alone in an empty restaurant; the son of a long-dead mother surrounds himself with her doll collection.

It’s a similarly isolated manner in which Lange has long preferred to work, citing both her shyness and her personal time in front of an intrusive camera as reasons why, until recently, she chose to take photos stealthily and without any detection. Engaging her subjects is a new habit that came from an experience working on 61: One day, riding her bike through New Orleans where she keeps a home, Lange encountered a group of school children rebuilding a home and, after striking up a conversation with one, she asked if she could take his photograph.

“It was really the first time I ever said this,” she explained. “He said yes, and that’s the photo on the cover. He just looked directly at me. I had my camera and there was some kind of wonderful exchange between the camera and him, and I began to appreciate more and more the direct gaze.” These portraits, a departure from her typical oeuvre, lend the collection a deeper, more arresting sense of intimacy. In a look, these people feel more like real people, and less like ghosts—to the viewer and the photographer alike.

“I think what I loved more than anything with some of these is the human connection and the encounter that you have,” she continued. “Not that you know them in such a short amount of time, but you have an encounter with somebody and it’s very human. It was actually some of my favorite stuff.”

Still, these shots appear rarely in the book, brief pit stops in Lange’s favoring of forlorn, barren landscapes and passerby as subjects. In these hardscrabble, forgotten road towns and their inhabitants, Lange finds the middle America endlessly pandered to on debate stages and in national news outlets, though there’s no sensationalizing, no posturing of “who will serve them best?” or faux-concern with understanding the Trump voter as a member of “the liberal Hollywood elite.” In front of Lange’s camera, there is just brutal honesty: a once lively America that is dying, and the people trying their best to survive on its rotten flesh.

Despite a long history of political candor, Lange also said Highway 61 was deliberately intended to be devoid of any political statement: “It was meant to be more of an emotional statement, my emotional response to what I saw. But, of course,” she added, “everything is shifting, whether it’s through climate change or economics or whatever. You can’t ignore that.”

It’s true; every day it becomes increasingly difficult to see clear lines separating the personal and the political. Lange’s vision of America in all its crumbling disrepair is a vital, relevant documentation of our shared history. But whether it was her intention or not, it also makes for a powerful political statement—one that, much like loneliness, is difficult to shake. FL