Amazon sold its first book in 1995—somewhat fittingly, it was Douglas Hofstadter’s Fluid Concepts and Creative Analogies: Computer Models of the Fundamental Mechanisms of Thought. In 2001, Amazon announced its partnership with Borders, an agreement that redirected the Borders website to Amazon’s online book marketplace. Just ten years later, Borders closed its last remaining stores. In a 1992 Census Bureau report, there were 13,136 independent and chain bookstores in The United States. In 2016, that number was 6,448.

Numbers reinforce an industry guard change we all understand on a more personal level with books, toys, electronics, furniture, groceries, and our everyday needs and knick-knacks. Enter a mall and be prepared to feel a sort of vague depression stimulated by the anachronistic storefronts, save for the lone clerks, scrolling their smartphones, biting their nails, straightening already straightened shelves. But some malls stay relevant with edison bulbs and VR experiences—four years ago, brick-and-mortar Amazon Books bookstores began appearing in this type of contemporary retail center, nineteen in total. Without knowing their figures, one can assume these stores—which primarily display Amazon bestsellers and just a shelf or two of the foremost classics—can hardly generate much added revenue for the web superstore. Rather, these storefronts denote banners: nineteen antagonizing monuments to the industry it efficiently and effectively disrupted, then displaced.

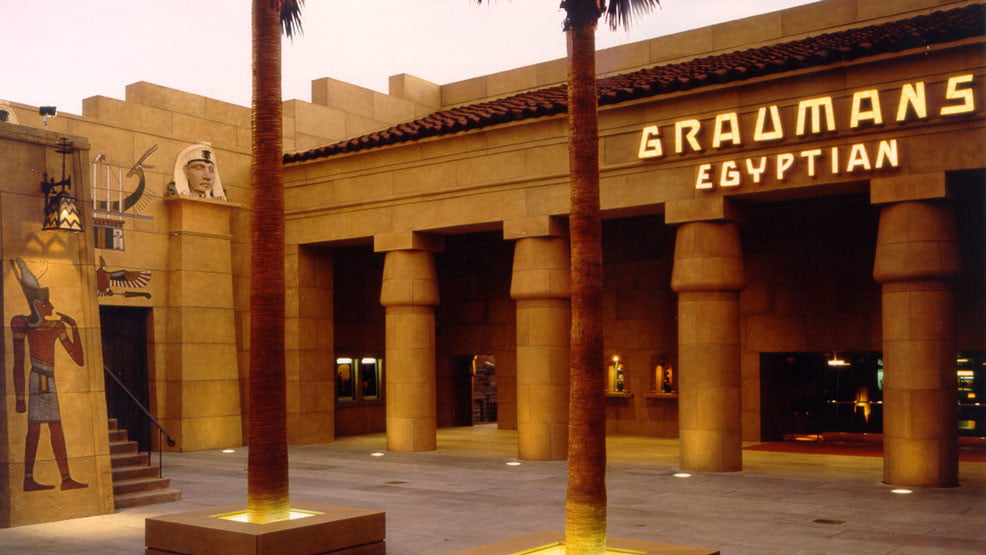

Now, for the first time, a streaming service will own and operate a physical theater to project its original films and series. Netflix is set to acquire The Egyptian Theatre, the second most iconic cinema house on the star-studded stretch of Hollywood Boulevard. The purchasing price is estimated in the tens of millions. Its current owner, American Cinematheque—a high-profile nonprofit dedicated to the preservation, projection, and celebration of classic and contemporary independent cinema—will continue to hold screenings on weekends. Beyond this, the official date of purchase, renovation plans, details regarding signage, and any official signature of contracts solidifying the Cinematheque partnership remain opaque.

What does it imply that the streaming service recognized as the forefather of the industry’s digital revolution purchases the first movie theater constructed in Hollywood?

The Egyptian was built by vaudeville showman Sid Grauman in 1922, four years before he erected the Chinese Theatre on the north side of the same strip. Significantly, The Egyptian hosted the first-ever Hollywood premiere, Robin Hood, the same year as the theater’s opening. What does it imply that the streaming service recognized as the forefather of the industry’s digital revolution purchases the first movie theater constructed in Hollywood, the first to host a premiere, and with a structure and name inspired by the civilization known well for their mausoleum-cum-totems for the pharaohs and queens of an era past?

Many know the story to some extent. In 2010, the effects of Netflix sharply surfaced when the ubiquitous Blockbuster chain filed for bankruptcy and its stores started to offload all its copies of Leprechaun 2, The Cable Guy, Jerry Maguire, and shutter. Just a few years later, Netflix shook things up in a bigger way with the production of its first original content program House of Cards, the success of which signaled the clear lucrative path forward to every major entertainment studio and corporate mogul with an interest in not just the financial potential, but also the influence media creators hold.

This history is well-outlined with refreshing objectivity by Ben Fritz in his 2018 book, The Big Picture: The Fight for the Future of Movies. It covers the emergence of Netflix, the Sony leaks, the rise of the superhero and franchise blockbusters, alongside the near-total demise of the mid-budget feature. Ben is also the West Coast editor for the Wall Street Journal, and offered a few insights for this article. Netflix remains outspokenly silent on the subject. American Cinematheque did not respond to requests for comment, but an unnamed employee did reply to an inquiry to say: “gonna be hard to get anyone to talk, frankly.”

“Netflix’s reported plan to buy the Egyptian is a great metaphor for where the entertainment industry is today,” Ben answers regarding the acquisition’s subtext. “Here you have this iconic, beautiful theater on Hollywood Boulevard that shows feature films on a huge screen in a large auditorium. Now a streaming video giant wants to buy it and use it to play the movies it makes, primarily for consumption on televisions, tablets, and phones. The Egyptian would become a marketing and publicity tool for Netflix—a place to show off its movies to press, creative professionals, and the small number of people who will pay extra to see a movie on the big screen they could see at home for free (if they already subscribe, as most people interested in entertainment do). The Egyptian would no longer be a business intended to make profits by selling tickets to films. Because, of course, that business is tiny now compared to the wealth of Netflix and its competitors in subscription streaming video.”

A substantial portion of The Big Picture addresses the shrinking of the theatrical film business. Essentially, once digital streaming was of a high enough quality, DVD sales plummeted (which had nullified poor box office performance throughout the 2000s) and viewers only visited theaters for massive spectacle films that they viewed as guaranteed entertainment and a cultural event. Mid-budget films became too risky to produce. Even though twenty mid-budget films could be made for the price of one superhero epic, that superhero epic had a massive guaranteed return, while each of the dramas, rom-coms, or single-star action vehicles would, on average, lose money—and when one or two did make money, it wasn’t nearly enough to float the others. This was specifically enhanced by the emergence of high-quality television series like Breaking Bad, and with home viewing easier than ever with services like Netflix, risking the price of a month’s subscription for a potentially bad drama in the theater became a non-option for most everyone except the most devoted cinemagoers.

The distinction between television and cinema is degrading. Ben explains that “previously they were very distinct because television was only one thing—twenty-two half-hour or hour-long episode seasons—and feature films were ninety to one hundred and eighty minutes and always shown first in a theater. That was dictated by the respective business models of ad-supported television and theaters that charged per ticket and need to cycle people in and out.”

“Netflix’s plan is a great metaphor for where the entertainment industry is today. You have this iconic theater that shows feature films on a huge screen. Now a streaming video giant wants to buy it and use it to play the movies it makes.”

— Ben Fritz

TV movies and series used to be identifiable by their lower quality due to lower budgets, and feature films were frequently helmed by higher-caliber directors and actors. This has since shifted, and feature films on streaming services are often (subjectively) of a lower quality than series, even when attached to heralded directors and stars. Exceptions abound, but television of varying lengths certainly appears the way forward for creatives and executives alike.

So, to return to the principal question: Why buy a theater when your business is founded on producing television? In large part, one can speculate, it’s because Netflix may be differentiating itself from the competition with a prioritization of the feature format. Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman is certainly a signal in this direction. When, in cinemas, there is little found between the low-budget, often subversive, output from A24, Neon, and Blumhouse, and the franchise tent-poles from the “Big Six,” there could be an underlying demand for the types of films that once represented non-independent theatrical releases, regardless of whether or not they actually appear in a theater. The Egyptian would symbolize this position, which further fuels the debate that surrounds streaming service films as Oscar contenders, since historically most Oscar winners were mid-budget films (if listed from lowest to highest budget, adjusted for inflation, the median budget for a best picture is $30.3 million, approximately that of No Country for Old Men).

“The discussion about what qualifies as cinema now seems hugely important, especially in terms of the Academy Awards,” Fritz continues. “In my opinion, there are basically two choices for the Academy and other institutions or people thinking about this issue. One is to define a movie as a piece of visual media that plays first on a large screen in an auditorium, where its creators intended it to be seen. The other is any piece of visual media intended to be completed in a single sitting (as opposed to an episodic series), no matter the type of screen on which it plays first. If you pick the former, you’re essentially excluding films from Netflix, Disney+, and other streaming services in the future that adopt their model. If you pick the latter, you’re essentially eliminating the difference between what we used to call ‘films’ versus ‘TV movies.’”

In today’s digital media-driven culture, it seems impossible to imagine a future where either the Academy does not loosen its requirements for Oscar contenders, or a new awards ceremony with a more inclusive, forward-looking modus operandi appears on the scene, prepared to recognize that the craft of filmmaking now sees its most venerable players dedicated to a format streamed principally on screens sized between seventy and four inches. Now, the conversation can explore all sorts of avenues, such as the qualitative differences in storytelling between cinematic feature films and television series created by and starring the exact same A-listers, or the significance of the ever-increasing democratization of media, where once viewers can easily place his or her own feature-length film on the world’s largest streaming platform, YouTube, and could “qualify” for the same awards as the likes of Scorsese with his Netflix films, and Spielberg and his future Quibis. However, these topics are perhaps better suited for a living room discussion amongst friends.

Netflix could emerge the hero, build a new awards ceremony, unite the streaming frontier into a cohesive recognition that they are all playing toward the same endgame: somehow keeping viewers interested in mainstream media for a long time to come, regardless of format. (I have to ask now, when will we revolt against the self-defeating and patronizing use of the word “content”?) The Egyptian Theatre might be just the mausoleum for such a ceremony.

Or, Netflix will use The Egyptian as its monument to the Hollywood standard it displaced, projecting its bulk of features and series to pervade the same air of classicism as the films that screened in this theater decades prior, and shall continue, purportedly, through the efforts of American Cinematheque.

Whatever the motive, Netflix is the undisputed forefather of the mass of services and media on our HDMI plates today. The winners of the “streaming wars” won’t be revealed for years to come—but the past is certain, and The Egyptian will be known, at least to those who are obsessed enough to think about it, as a relic of a relic of the past. FL