In an era where the term “power pop” has frequently come to signify formulaic four-chord constructions with a dash of mild guitar jangle and a splash of Beatles backwash, it’s especially instructive to go back and give Big Star’s first two albums a spin.

Originally released in 1972 and 1974, respectively, #1 Record and Radio City can still take your breath away with their bracing guitars, soaring melodies, emotionally-charged lyrics, and song structures that often zag when you’re expecting them to zig. Though the Fab Four are an audible influence on the albums, it’s generally more White Album–era Beatles being drawn upon than A Hard Day’s Night, along with such disparate elements as Led Zeppelin’s swaggering hard rock, Kinks leader Ray Davies’ brooding introspection, and the sweet soul music of Big Star’s Memphis hometown.

Of course, despite the albums’ optimistic titles, such a potent and unique mixture was anything but a sure-fire recipe for success in the early/mid-1970s. Bearing little resemblance to the music on the AM or FM dials at the time, and hampered by music industry shenanigans, both records completely flopped when they were released on the Stax-affiliated Ardent Records. Chris Bell, who split the singing, guitaring, and songwriting duties with Alex Chilton on #1 Record, was crushed by the album’s failure to chart and left the band soon after; Chilton took the wheel for the sparkling Radio City, but would soon steer the band (and his subsequent solo career) into darker, more experimental waters.

But as with The Velvet Underground before them, Big Star’s lasting influence would far outstrip the number of units initially moved. R.E.M., The Replacements, The Bangles, Teenage Fanclub, Wilco, The dB’s, Matthew Sweet, and The Posies are among the many alt-rock artists who have sung the band’s praises (and, in some cases, their songs) since the 1980s, while Cheap Trick would re-record #1 Record’s “In the Street” for the opening theme of the TV sitcom That ’70s Show. Big Star’s three albums (including 1978’s 3rd, a.k.a. Sister Lovers) have been reissued multiple times since the mid-’80s, and a documentary film (2012’s Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me) and several books about the band and its members have kept the Big Star story alive well into the twenty-first century.

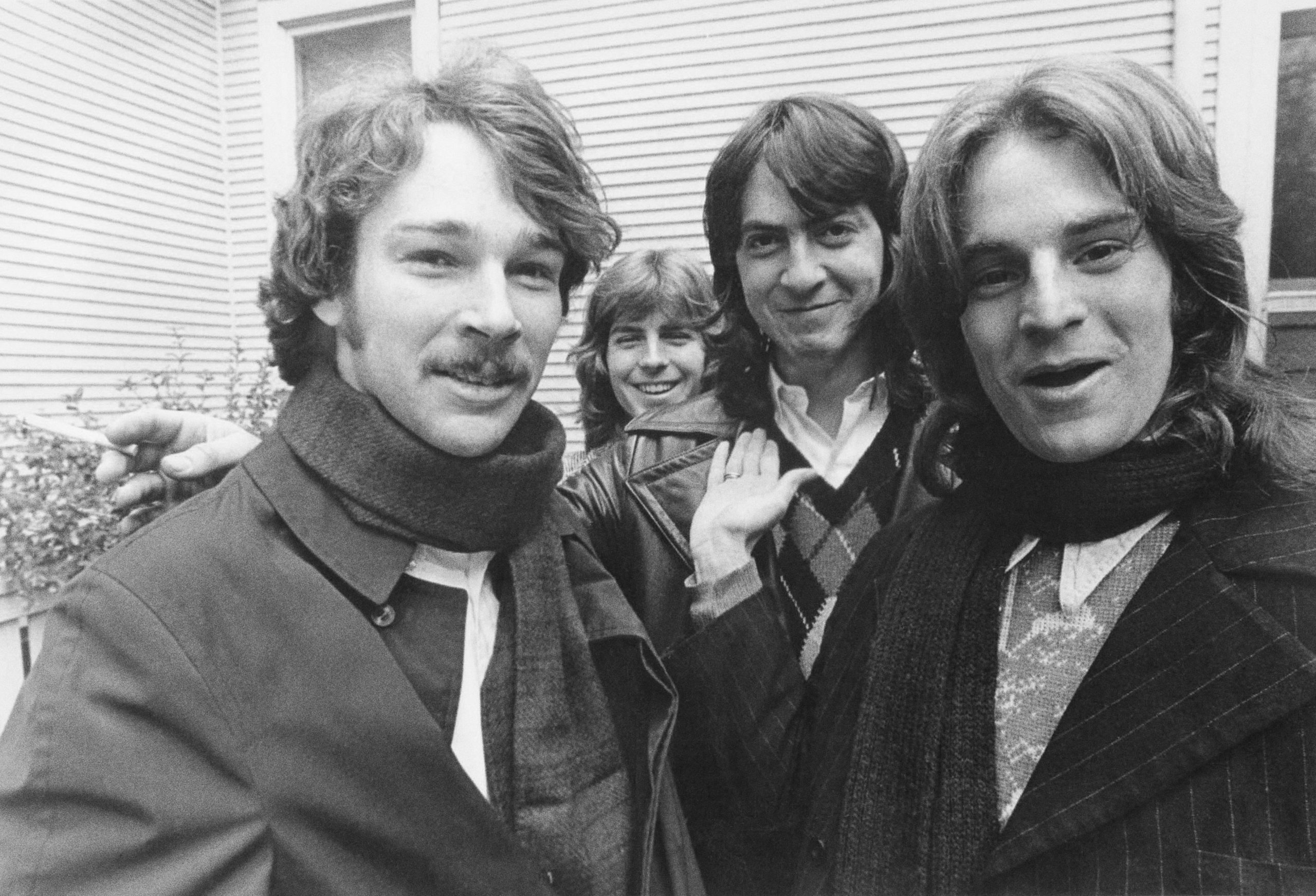

On January 24, Craft Recordings will release new 180-gram vinyl editions of #1 Record and Radio City, both featuring all-analog mastering by Jeff Powell at Memphis’ Take Out Vinyl. Sadly, Bell, Chilton, and bassist Andy Hummel have all left this earthly realm; but Big Star drummer Jody Stephens—now the Vice President of Ardent Studios, the same place where #1 Record and Radio City were recorded—generously took the time to speak with us about these two brilliant albums and their enduring legacy.

Why do you think these records have such staying power nearly fifty years after they were released?

I just have to explain it by what attracts me—and that’s Alex and Chris’s voices, and the material and the melodies. Some people just have this built-in depth to their voice that people relate to and kind of connect with. I mean, if you listen to a demo that Chris might do on an acoustic guitar, or something Alex might do, the song’s complete—the message is there, and the emotion is there. So for me, as the drummer, it was all about not getting in the way of that [laughs].

I was lucky, because those guys were inspirational, and whatever I played was inspired by the way they sang; I paid more attention to the vocals, and the guitar second—and somewhere along the way, I figured out that, “Whoops, I need to pay attention to what Andy’s playing!” Andy was a brilliant bass player, and it wasn’t just standard bass lines.

How did the music you were playing together relate to what else was going on in Memphis at the time, at least in terms of rock music?

You know, by ’72, ZZ Top was around [1973’s Tres Hombres was partly recorded at Ardent Studios], and blues rock was a big thing here. You could either say we were early to the game, or late, depending on your perspective [laughs]. Because we were all influenced by The Beatles and Rolling Stones and Kinks—and for Chris, Andy, and me, Led Zeppelin.

There’s a definite Zep influence evident on several tracks on #1 Record, especially on “Feel.”

Yeah, undeniably! Chris’s vocal delivery, if you think about it, you can tell where that’s coming from. The three of us, anyway, were Led Zeppelin fans; I don’t know about Alex. I’m pretty sure the three of us went to see them in 1970 at the Coliseum. Watching them, it was like, “For me, that’s unattainable—so I just need to work on my own little bit of character, and my own way of doing things.” I could borrow and be inspired by certain things, but good god almighty—Bonzo was a monster! [Laughs.]

“We weren’t adhering to a formula, or anything; we were just kind of doing what inspired us all. And we were also lucky that we didn’t have anybody looking over our shoulder.”

So yeah, that all sort of played into it, but we were just lucky. We weren’t adhering to a formula, or anything; we were just kind of doing what inspired us all. And we were also lucky that we didn’t have anybody looking over our shoulder. John Fry [founder of Ardent Studios and the Ardent Records label] was there to support and enhance what we were doing, not to deviate us from what we felt was natural.

You started #1 at the original Ardent Studios on National Street, and finished it at the newly-opened Ardent Studios on Madison Avenue. What was the difference between the two studios?

Well, we had all gotten used to the one on National. We’re lucky that we had got all the basic tracking done over there, because the comfort we felt in that place was definitely reflected in the record. And then when we got here, we did vocal overdubs, and we did the mix here in Studio A.

I’m assuming the vibe of the new studio was very different.

It was different, but it was also pretty exciting. It was all brand-new equipment in Studio A, and there was a whole new energy to it. We were right on the edge of Overton Square, which was a big entertainment area; we had Trader Dick’s right next door, this really popular bar. And just a couple of blocks away, we had Lafayette’s, which is where we played a couple of times—the rock writer’s convention [for which Big Star regrouped and performed in 1974], the performances were at Lafayette’s, and Billy Joel, Linda Ronstadt, and KISS all played there. And Friday’s [where Radio City’s back cover photo of the band was taken by William Eggleston] was right there. So there was lots of drink and good times to be had, within feet of our front door. And I’m sure that reflected on Radio City, and a whole lot on 3rd, because people would go next door and drink, and then come back and do some late-night recording. We all had keys to the studio. But it also had kind of a dark influence on things, because there was lots of alcohol, and a lot of people partying.

That partying vibe was definitely more apparent on Radio City than #1 Record.

Yeah. I mean, it’s not like that’s a “party” record [laughs]. But the drink that goes along with hanging out at bars certainly had an effect, I would think. Me, personally, I would drink, but not very often—because I couldn’t afford it. Unless there was a record promoter in town who would have a table at Lafayette’s, and we’d get to sit at his table. But other than that, if I was hanging out, I wasn’t really drinking; and if I had a couple of drinks, the last thing I wanted to do was go back into the studio and go to work. I just wanted to go to bed!

Tell me a little more about John Fry’s role in the making of these two records.

John was definitely running the show on those records. And whatever you think of the music, sonically those albums are just brilliant—and that’s all John Fry. I don’t know how to explain it, other than maybe he created the sonic frame that the music was displayed in. He really used the studio as an instrument. And John Fry and Larry Nix would master the records; instead of just running everything through a limiter or compressor, to clip the high highs and the low lows so the music would fit on the record, John would do it manually, because he would know where there would be a bit too much high frequency.

Chris had high expectations for the success of #1 Record. Did you? Or were you just happy to have made a record?

More of the latter. We did this great record, at such an amazing time—it was like a record of “how I spent my summer vacation,” in a way. I just marveled at the way it all came together. I’d gone from being in what was primarily a cover band, where all the songs were laid out for everybody, with nothing much to create; you just had to have your chops up and be able to perform what someone else had written. So with #1 Record, I had to create these drum parts, which was challenging. But once I got into it and just let go, then I could tune in to Alex or Chris, and the rest took care of itself.

Big Star disbanded for a while after Chris left. When you went back into the studio with Alex and Andy for Radio City, was it pretty easy to click back into working together?

Yes. And to go back to your earlier question, I was expecting #1 Record would do great things, because it was a great record! And, you know, I tend to think—incorrectly—that my tastes reflect the tastes of a lot of people. It didn’t work out, but that was OK. But then, when we get in to do Radio City, I’m thinking, “Wow! ‘September Gurls’!” That intro on Alex’s Strat—it’s like a clarion call that grabs your attention, and dictates whatever energies are about to fall in. And “Life Is White”—I can still remember that song coming together.

Like #1 Record, Radio City is a sadly ironic album title, in that it really doesn’t sound like anything that was on the radio in 1974.

I know! You apparently know where “Radio City” came from—if something was a drag, it would be, “Drag City, man!” [Laughs.] Andy thought it was a radio-ready record, and he’s the guy that came up with the title. And you’re right—in retrospect, it didn’t really sound like anything on the radio. I don’t know that I ever had any expectations like that for the album; maybe I was just pessimistic, but I’m sure I thought it was a long-shot. But we got to go to New York and play Max’s Kansas City, and we even stayed at the Plaza Hotel the first time we went up there, and then we stayed at the Gramercy Park the next time—it was a really good time! I got to see a little bit of New York on Stax’s dime, so I was having a good time, and we got to do some exciting things.

“I was expecting #1 Record would do great things, because it was a great record! And, you know, I tend to think—incorrectly—that my tastes reflect the tastes of a lot of people. It didn’t work out, but that was OK.”

When did you first realize that these records were influential?

The first time, from what I remember, was through [R.E.M.’s] Mike Mills and Peter Buck. I would have liked those guys, anyway, but liking them was built in by the time I finally met them, because they would say really nice things about Big Star in their interviews. And that was cool, because the first time I heard them, I was an immediate fan; not that we sounded like each other, but it came from the same sort of spirit.

Alex Chilton was often pretty dismissive of the first two Big Star records, as if he almost resented the continuing fascination with them.

You’re right. But I also remember him saying in a radio interview that Big Star was “a band that turned a lot of heads,” or something like that, and it kind of made me proud that he would acknowledge that publicly [laughs]. I don’t know; I think he was more focused on whatever he was doing at the moment, and I don’t think looking back had that much value to him. But later on, we got together with Jon Auer and Ken Stringfellow in the ’90s and did those dates [as Big Star] and an album [2005’s In Space], and I’ve never known Alex to do anything he didn’t want to do…so he must have wanted to do that. I never paid too much attention to comments that Alex would make about the band.

But did you ever feel similarly disconnected from these records?

No, not at all. It’s just become this kind of common denominator. I meet people who want to talk to me about those records; I get to play with Mike Mills [in the all-star touring band Big Star’s Third, which also features Chris Stamey and Mitch Easter], I recorded a little bit with Matthew Sweet, and got to go into the studio with Elliott Smith. And this band I have now with Luther Russell, Those Pretty Wrongs, you can hear a little bit of Big Star in there, too. I get to do all these things that are the result of Big Star, so it would be hard for me to disconnect, even if I wanted to. But I don’t want to! FL