The Unicorns were as fantastical as their mythical creature namesake. Alden Penner, Jamie Thompson, and Nick Thorburn never meant for us to take the project very seriously, but their horny-existential-spooky lyrics (“I want to die today and make love with you in my grave”), deconstructive pop structures (they were among the earliest indie-rock groups to incorporate hip-hop conventions), and facetious press interviews quickly made them an adored underground project. “The Unicorns were always impish, trying to prank and subvert audience expectations,” Thorburn told Stereogum years after disbanding. Speaking on their brief 2014 reunion, he added: “Doing those shows was fun because it was about being silly and tricking people and not being too precious about anything.”

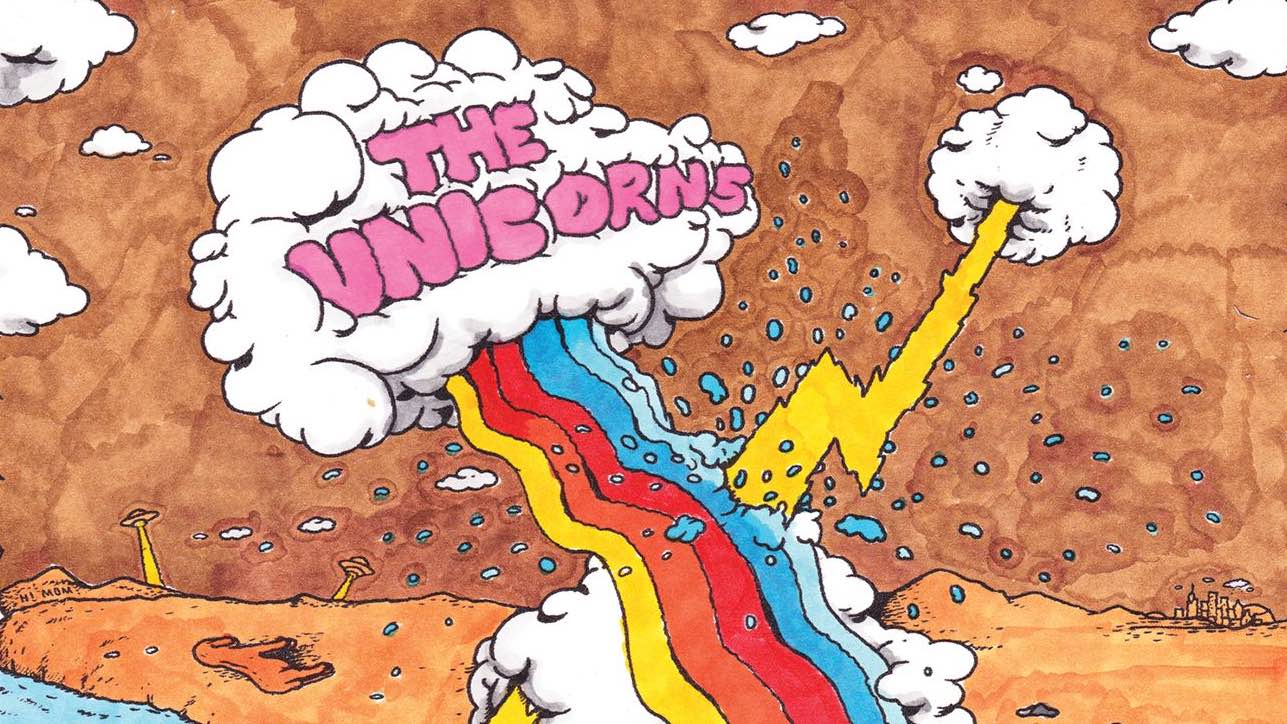

The Canadian outfit released their debut album The Unicorns Are People Too in February of 2003, only to be followed up immediately by their magnum opus, the cult-classic Who Will Cut Our Hair When We’re Gone? several months later. And several months after that, The Unicorns disbanded. What they’ve left behind is an unruly legacy, trapping the tension of irreverence and the seriousness of self-mythology in uncanny pop amber.

Part of what makes this album a timelessly cathartic joy is the way The Unicorns flippantly deal with always-relevant existential dread. Opener “I Don’t Wanna Die” sees the band contemplating their preferred mode of death over anxious keys and a withering melody before ultimately rolling things back: “Death / I just want one more breath / Can you grant me one more, please?” Thorburn cries alongside bulbous horns.

Lou Reed comes to mind when hearing their surreal absurdity delivered with Thorburn and Penner’s alternating frank earnestness. As the album progresses, they explore the Earth’s glorious heights (“Ghost Mountain”) and eerie depths (“Sea Ghost”) only to be confronted by supernatural forces imploring them to fuck off. They’re confronting serious themes—death and the afterlife, mankind’s contentious relationship to nature—with the hyper playfulness of a sugar-high toddler.

What The Unicorns have left behind is an unruly legacy, trapping the tension of irreverence and the seriousness of self-mythology in uncanny pop amber.

Other moments on the record where The Unicorns contest crippling mortality with legacy and fandom feel even more poignant today. On “Let’s Get Known,” the group imagines the possibilities of fame: “Say, let’s get known / If we keep it up, we’ll show all the haters.” It’s a line that feels even more loaded and sinister after the song’s opening sample mentions some sect of an organized group taking interest in violent Satanism. The static-cloaked snippet feels like a nod to secular music’s history with Satanic conspiracy theories, but it also emphasizes the growing desire to make cultural waves at any cost.

Later, it seems like the trio are poking fun at the ingrained human desire for superficial longevity. “Do you want to make love to my sweet visage?” an aged celebrity asks a lusting fan on “Child Star.” In turn, The Unicorns delivered a poignant representation of the battle between Fan and Idol. “I’m still a big, big star,” goes one line, with the fan disagreeing. “I’m not a fan of yours anymore,” Penner meekly responds to Thorburn. “But you broke my fragile heart.” A sparse programmed drumbeat and a weepy, haunted-house organ mingle with slyly aggressive guitars. It’s gross and it’s hilarious, but above all it’s eerily relevant to the current curdling of standom. The Unicorns validate that this is a common temptation when faced with the anxious reminder that we’re all gonna die someday—they laugh off the absurdity of how some of us spend our precious time on Earth.

The same playful tension defining “Child Star” exists throughout the scarce press the band did that still exists online today. There were rumblings of connections to Celine Dion and dabblings in Scientology in writeups that are equal parts confusing and fun to read. Their irreverence feels punk, but also hinted at the combustible tension simmering among the group. “All of the songs are just metaphors for the tension within the band,” Thorburn said before the outfit briefly reunited in 2014. “We were basically like Fleetwood Mac in that regard. We weren’t having sex with each other’s girlfriends, or each other, but we were definitely at odds, and a lot of the songs reflect that. The tension raised the stakes, and made things more meaningful.”

The Unicorns flipped the hell out of a pop song and exposed how our world’s escalatingly insane reality contrasted with the most microscopic magic inherent to Earth.

In a sense, one of the band’s greatest accomplishments was calling it quits when they did, and their untangleable mythology is among the many gifts (see also: Islands, Clues, and any number of Thurburn’s additional extracurriculars) of their piñata-like demise. In an early interview Thorburn explained: “Music has a lot of potential to make a lot of things hurt a lot less.” Penner took it to a philosophical level, drawing on Camus to express that “music acts as an anchor to clarity. In a similarly existentialist way, I think there is a comment about absurdity on many levels. And, in drawing upon the subject of the human perception of the unicorn as myth, also an avenue for transcendence.”

The Unicorns flipped the hell out of a pop song and exposed how our world’s escalatingly insane reality—possible nuclear apocalypse, child stardom, etc.—contrasted with the most microscopic magic inherent to Earth (ants get a shoutout on “Let’s Get Known”). Two decades later, they still have us asking why we value life—both the planet’s and other humans’—the way we value the myth of horned creatures that are more than horses. FL