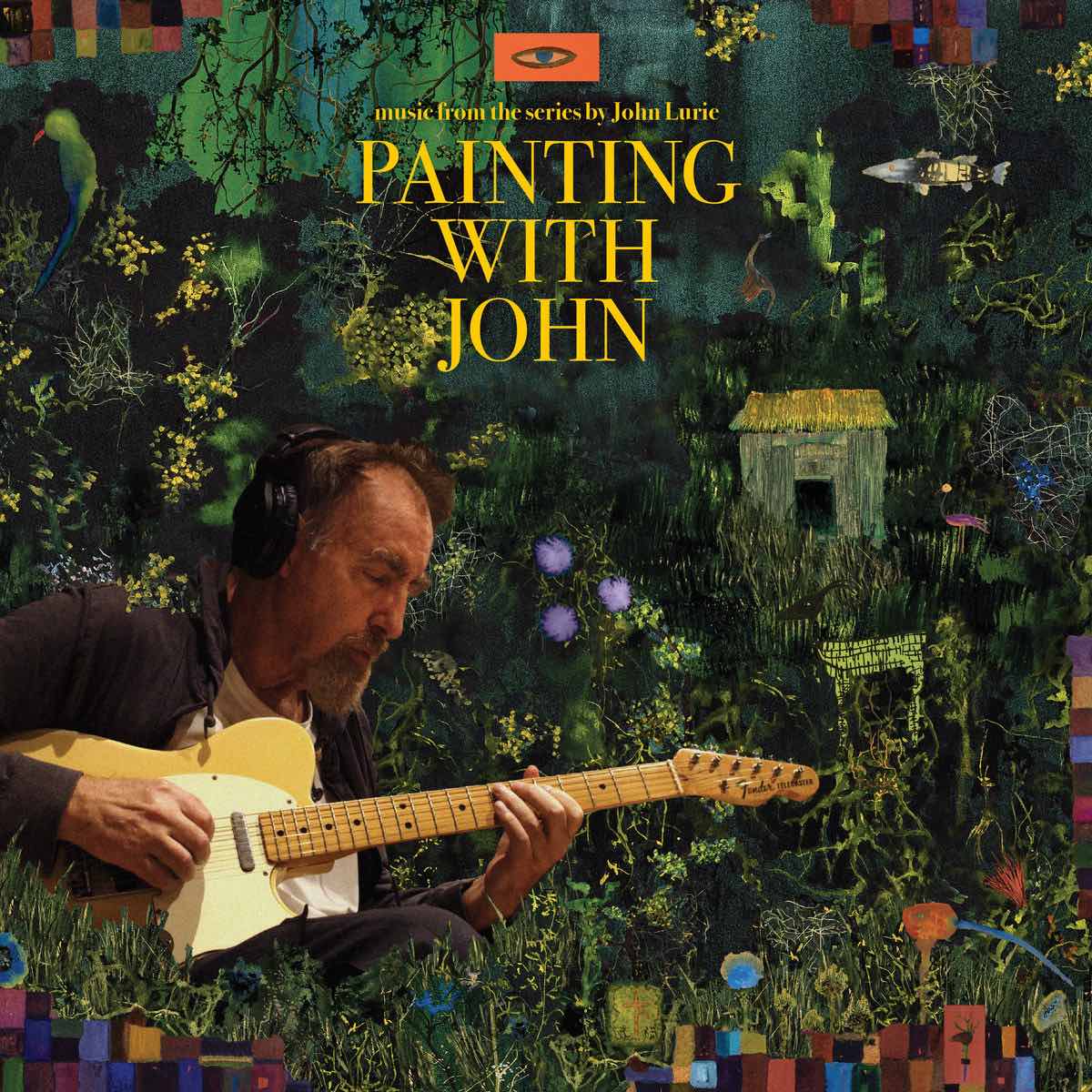

John Lurie

Painting with John

STRANGE & BEAUTIFUL

There have always been two John Luries when it comes to recorded music: the enigmatic, saxophone-wielding figure whose wiry Ornette Coleman–like compositions filled more than a few Lounge Lizards albums (to say nothing of one LP from the John Lurie National Orchestra and his blues studies under the Marvin Pontiac moniker), and the multi-instrumentalist behind expressionistic soundtracks to his own filmed productions, such as Fishing with John in the 1990s and the current series Painting with John.

Beyond a backstory worthy of its own screenplay (e.g. being stalled for over a decade by a career-ending strain of Lyme disease and an up-close interaction with a stalker), Lurie’s s third (or fourth) act has been filled with the creation of primitive paintings and drawings touching on animalistic figures and their environments, and a pithy HBO series documenting that rebirth, which is at least nominally about painting. What was slower to follow—until forced to create exclusively for the HBO series—was new music. Bound together by a handful of Lurie-song from previous recordings is a wealth of fresh music guided by spirits divine and self-determined whose overall effect is shapeless, cluttered, and serene.

Now utilizing musical familiars from his various Lounge Lizards lineups (including brother/pianist Evan Lurie, drummer G. Calvin Weston, and skronk-centric guitarist Smokey Hormel), John Lurie seems to have borrowed theoretical elements from his harmolodic 1980s to bear on a set of new sounds nestled in the primitivism displayed in his painting. To that end, sunburst bolts of color in short spurts (“Dervish Banjo,” “Unky G”) meet up with languid, repetitious tracks (“Sea Monster,” “Africa Swim Main Titles”) in all their polyphonic glory. Aided occasionally by cellist Jane Scarpantoni and his own broken banjo plunks and sawing, there’s a crepuscular orchestral elegance to the proceedings—a noirish sound that lifts his dirty rhythms and musky horn charts into something celestial and nighttime-twinkly.

As he says in the notes to the soundtrack to Painting with John, “This may be the last thing I do. I want it to be beautiful.” Make no mistake: John Lurie has achieved his mission.