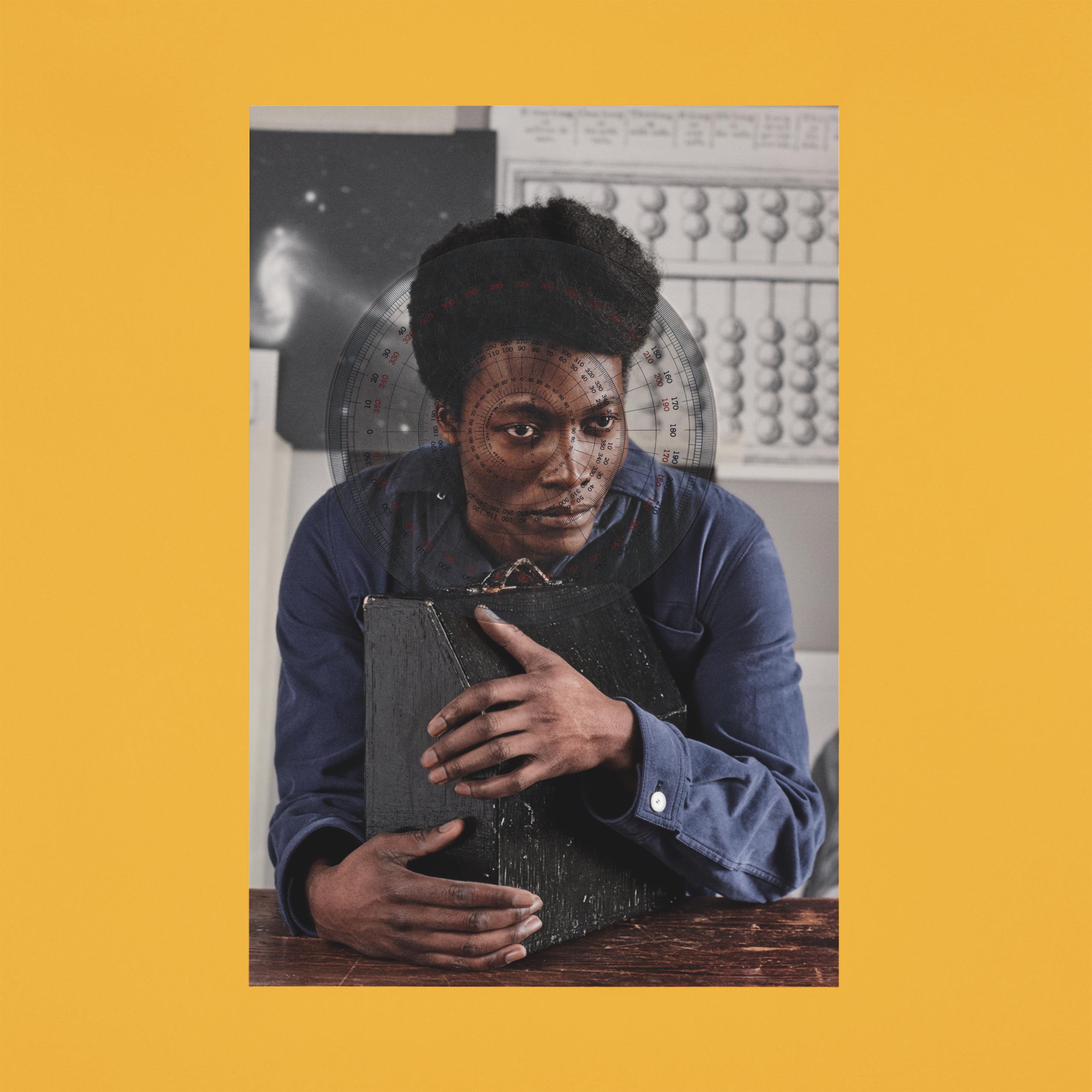

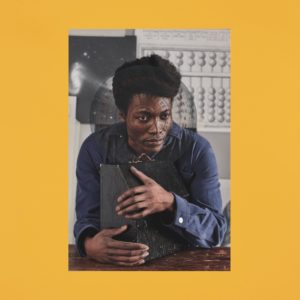

Benjamin Clementine

I Tell a Fly

CAPITOL

7/10

British poet and musician Benjamin Clementine won a Mercury Prize for his first album, At Least for Now, then wrote the second largely within the United States, the 2016 presidential election looming all the while. The resulting song cycle, I Tell a Fly, is composed from a familiar place of dislocation, one articulated by many marginalized and minority artists before (not least Kendrick Lamar). Clementine has found great success in a world that generally chews up and spits out people who look and sound the way he does; he is a big star and a total alien, on a pilgrimage through hostile lands.

I Tell a Fly is not a political screed so much as it is a memoir, a piece of self-confession that captures vividly the feelings of being outcast—and generally without broaching on the polemical. Actual space aliens are evoked more than once, and the songs touch obliquely on the refugee crisis, the rise of nationalism, and ongoing fear of the other.

Oh, and one more thing: These are basically show tunes, cabaret piano pieces delivered with the lilt of the stage; Gilbert and Sullivan by way of “Mississippi Goddam.” They’re anchored by Clementine’s conservatory-ready piano playing—passionate, delicate, precise—as well as his voice, not quite hiding his anxiety or his hope in its theatrical intonation. The arrangements are spare enough, and Clementine’s presence sufficiently magnetic, that it’s easy to tune out everything else and imagine these as solo pieces, though he’s offered restrained support throughout.

The tunes and arrangements match the imagination of his words, too—notice how “Farewell Sonata” opens the album with classical sweep, how ticking percussion lays out the menace in “God Save the Jungle,” how “Jupiter” smuggles in an R&B groove while “Paris Cor Blimey” plays up Victorian grotesqueries, right down to the harpsichord.

His performative approach may be what makes these songs—presented here with the unbroken momentum of an opera or a symphony—feel so inviting; on their own, they sketch out a creeping sense of unease that’s hopeful only in how it seeks out the humanity in an increasingly inhumane world. There’s a tune about the Syrian crisis, called “Phantom of Aleppoville,” which sounds like a monster-movie scenario, and maybe it is: Rather than focusing broadly on politics, Clementine pans in for a more intimate account of bullying and abuse, and how they can both fester into a lifelong fascination with cruelty. It’s scary stuff, delivered in a tune you can hum along to—proof, perhaps, that song is as good an antidote as anything to these bleak times.