The French electro unit of Gaspard Augé and Xavier de Rosnay may have formed Justice in 2003 to fuse the thunder of heavy metal with the chill of house music. But, by 2011’s Audio, Video, Disco and its accompanying tour, the duo began stripping away their use of video and color itself, to focus instead on scorched earth sound and minimalistic vision.

By Justice’s next big show, 2014’s “Woman Worldwide Tour,” they’d gone even further, using black as their palate and incorporating intricate, moving stage lighting fixtures. Only a signature cross, the band’s symbol since the beginning, remained as Justice’s visual touchstone.

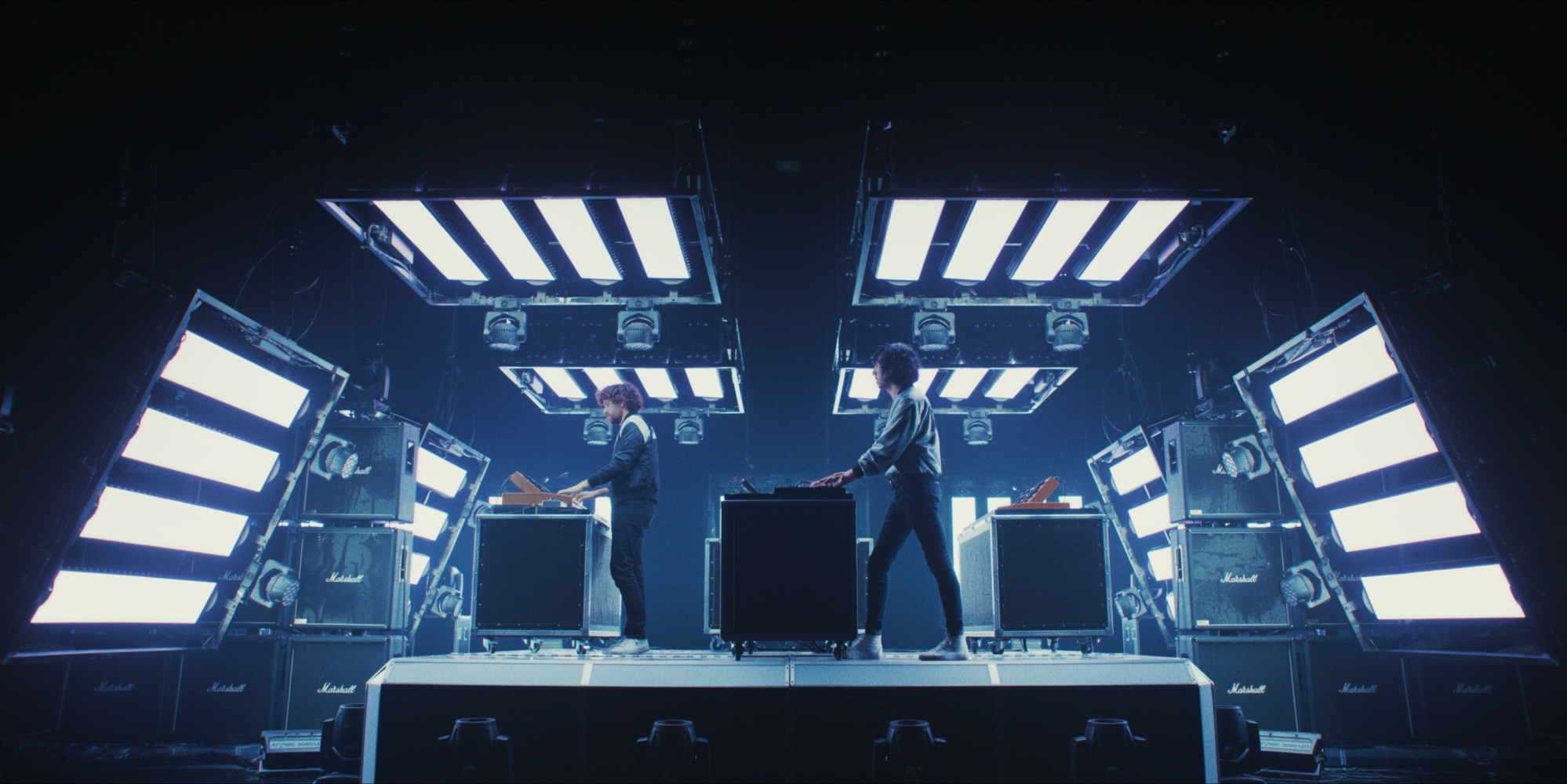

It is here that Justice’s cinematic escapade, IRIS: A Space Opera, begins. Filmed without an audience, Augé and de Rosnay, both clad in all-black, stare at themselves; without the interaction of a crowd, their sequencers and their analog synthesizers allow the viewer to center on space, or at least their version of it. Never before has a massive, moving lighting rig or a set of retina-burning strobes ever been a filmic co-star.

De Rosnay alone (we’re told Gaspard says “hi” and “apologies,” as he had an appointment) gave us the skinny on the “woman” behind IRIS, why a crowd is bad for a live music film, and what their cross symbol still means to them after all these years.

How long has the concept of a filmed space opera been floating around in your heads, and how did you imagine it as something different from your usual compositional/recording/touring process?

We’ve had this idea at two different times. The first time was twelve years ago, when we started touring. We tried to film shows, for what might be a live film, but it didn’t work. We tried again, but never managed to perfect what we wanted. We couldn’t capture the live energy. We couldn’t understand why. It was all shelved because it was not good. During the last tour, we talked about newer ways, better ways to put this all on film and be beautiful. We thought maybe we should not try to translate the energy of a live show onto film, but instead focus on the music and the visual effects. For that, we would need to not film it with an audience, but instead, a controlled environment, so we could script every movement of the camera and have it be where we needed it to be.

The irony of successfully filming a live show, finally, without an audience can’t be lost on you. It does feel like a stadium show in the middle of a void.

We rehearsed a lot, maybe two or three times more than for an actual show where we play for people. Being filmed in front of nobody…you can play the same way over and over. Playing live there are differences, because there are interruptions.

You mean human interaction.

There are sound differences. The same with our body language. We don’t have an audience with which to respond. In the director’s eyes, it looked better this way. Good, good, good. We didn’t have to pretend there was a crowd there, going crazy, and creating its own energy.

I get that. You guys don’t seem to be guessing. But you’re certainly not from the world of improvisation. How did your gut instincts tell you this would work? That there is a soul inside of the machine?

I get that. You guys don’t seem to be guessing. But you’re certainly not from the world of improvisation. How did your gut instincts tell you this would work? That there is a soul inside of the machine?

There is always a risk that something will not happen. Look at our previous attempts. We kept up our hopes that our ideas were good, but we were not 100 percent. It was only when we saw it back, the last moments, that we knew we were onto something. Even with the best idea, there are a thousand ways to fuck it up before the end.

Who is IRIS anyway? It could be a woman you’ve lost, as I can hear voices singing about romance toward the film’s end. Or is it closer to the idea of something comforting, homey, yet totally artificial and intelligent, such as Alexa or Siri?

“Even with the best idea, there are a thousand ways to fuck it up before the end.”

Good. Yes,it’s the latter. IRIS is something we imagined would welcome you aboard a spaceship It sounds like the name of a NASA project.

By calling it a “space opera,” there is a connecting thread inferred.

Of course, the music of IRIS is made up of all of all usual elements. It’s part of the dramatic build up. But now, the main reason we looked at it as our space opera is due to all the space operas we grew up with as kids such as Blade Runner, Alien, and even Star Wars.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind has to play a part in that space opera inspiration, as there is one moment in IRIS where you have orangey amber light bars pulsing in time to the beat.

Yes, of course. Close Encounters was our first direction when we designed the lights set up in IRIS. That effect—with the spaceship and the blend of cold and warm light, very orange and very blue—came from there.

Considering the musical arrangements in IRIS, you started off with rounder, softer edges than I’m used to hearing from Justice—more strings and chorales as in early classic disco—before going into your usual heavy metal thundering. Was that also a dramatic trajectory, or is it that your ears are beginning to hear ( or want to hear) things far differently from the tumult?

Considering the musical arrangements in IRIS, you started off with rounder, softer edges than I’m used to hearing from Justice—more strings and chorales as in early classic disco—before going into your usual heavy metal thundering. Was that also a dramatic trajectory, or is it that your ears are beginning to hear ( or want to hear) things far differently from the tumult?

I don’t know. The initial songs are softer. And the great signer of our sound has always been disco. Then not disco, but funky. And saturated. But certainly it is all meant to build, so yes.

This might seem like a silly question, but since your biggest co-star is IRIS’ spectacular strobing effects, I might as well ask: After all this time, and all those strobe lights, how do you keep from being bothered by the flash?

“Close Encounters was our first direction when we designed the lights set up in IRIS. That effect—with the spaceship and the blend of cold and warm light, very orange and very blue—came from there.”

That is not at all a silly question—a rather good one, I think. We learned long ago to face all of our strobe lights from behind us and into the audience, so that we never have to look at them. We don’t see them, and it looks nothing like what you’re seeing in the audience.

Symbolically, you guys have been using the cross as your tag since your start. Whether it’s religious, political, or just graphic, how has the use of the cross changed for you since your start?

It hasn’t changed, really, at all. From the beginning, it was more of a fun idea of using something that had been used before, from Madonna to George Michael to Black Sabbath. It has always been used in some subversive way. We all know that. We wanted to use it not only in a non-subversive way, but as something positive. More in line with the idea of a gathering, and having a lot of people wishing on the same thing or the same direction. It is something that everyone could recognize, and we still like the gathering feel of it. Now every time I see a cross—no matter what setting—I think of my band before thinking of the church, or whatever. That’s nice too. FL

Get tickets and find your local screening of IRIS: A Space Opera here.