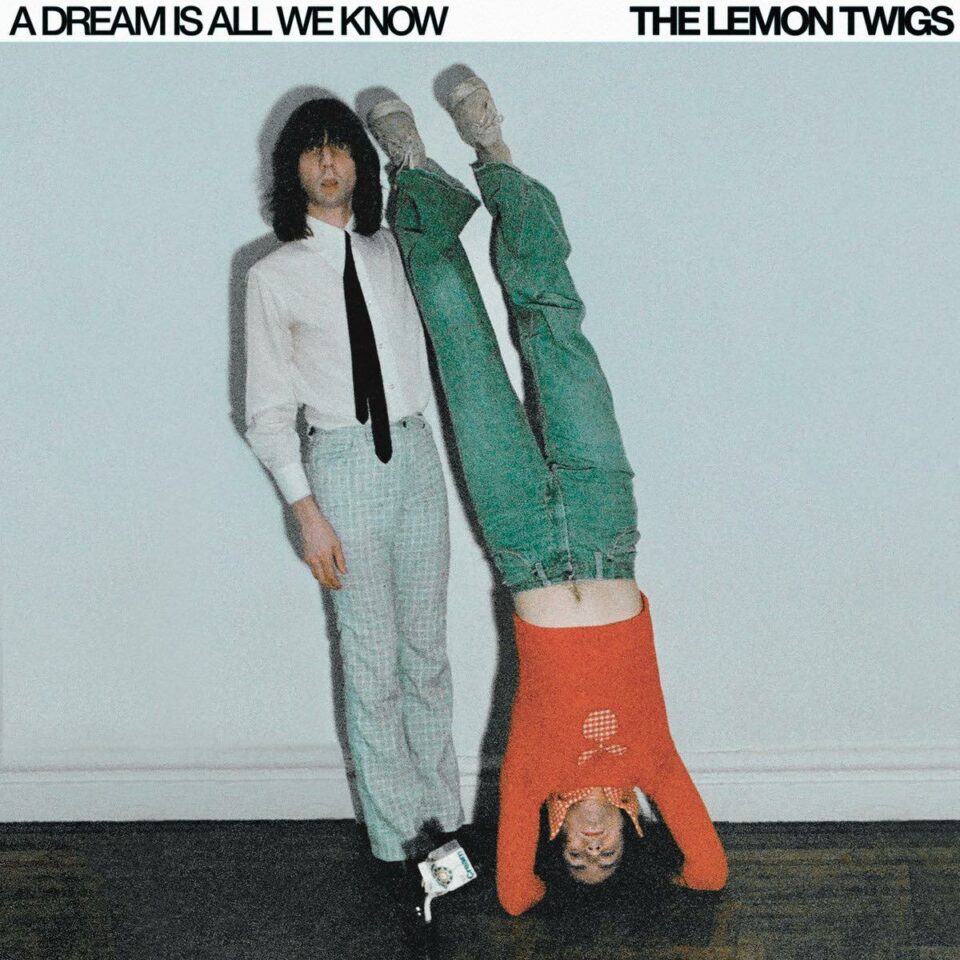

Beyoncé

Cowboy Carter

PARKWOOD/COLUMBIA

ABOVE THE CURRENT

Whether she made a classic Beyoncé album or an equally genre-blurring second act to Renaissance’s house music, Cowboy Carter is a tireless, fearless 27-track epic of quirkily and wisely told Black history and its poignant ties to Nashville prejudice, featuring elements of the vocalist/producer’s Texan origin story and circulating catty currency as its kicker. I mean, what other present-day artist could weave the ageless dynamics of Blackness and the necessary messages of empowerment with snarky swipes at the GRAMMYs for her consistently losing Best Album honors, among other shade-throwing?

Potentially Beyoncé’s most important work, as well as her most varied in arrangement and voice, Cowboy Carter utilizes (and, in some cases, interpolates) the traditions and towering classics of country—Black and white—while hitting her sweet spot of complex melody, then shakes, bakes, and mutates the frothy whole to form an eccentric tale of how America was made; how racist screeds, deeds, and exclusionary language never die until you push the issue; how power and love interact; how family is everything; and…spaghetti.

To the rare, shockingly spare accompaniment of mostly acoustic instrumentation and opulently stacked vocals, Bey fuses country and R&B as did Ray Charles: with an ear toward the contemporary and without straight symmetry. The shimmering balladry of “16 Carriages” and its personal take on coming up as a singer lit by starshine, her robustly intoned, spite-over-sorrow lyrical redo of Dolly Parton’s “Jolene,” and the humorous-but-savage murder psalm “Daughter” merge the twang of country and the pangs of soul seamlessly. If you’re looking to hear how Bey borrowed from Ray’s way with gospel C&W, look to “Smoke Hour ★ Willie Nelson” with its sliced-and-diced bits of Chuck Berry’s “Maybellene” and Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s swaying “Down by the River Side” in its chunky sauce.

While Post Malone duets with Bey on the pillowy-talking rhythm-and-folk of “Levii’s Jeans,” and Miley Cyrus joins in on the barnstorming, Nicks-ian ruckus of “II Most Wanted,” it’s a cover of Paul McCartney’s civil rights beauty “Blackbird,” retooled as a choir’s prayer for young Black women with the assistance of Brittney Spencer, Tanner Adell, Reyna Roberts, and Tiera Kennedy, that’s most haunting. Though great partnerships, all (and let’s not forget the appearances of Black C&W legend Linda Martell alongside Dolly and Willie), my money is on Beyoncé doing it alone: the cocksure hucklebuck bounce of “Ya Ya” and its not-so-subtle samples of “These Boots Are Made for Walkin’” and “Good Vibrations.” Or the yacht-rocking “Bodyguard.” Or the surprising giddy-up trap-club thump of “Tyrant” and “II Hands to Heaven.”

Though it’s been a steady part of the cultural conversation since the Super Bowl and the chart attack of “Texas Hold ’Em,” truly nothing could prepare you for the wealth and stealth of Cowboy Carter in its immense, nearly 90-minute entirety. And yee-haw to that.