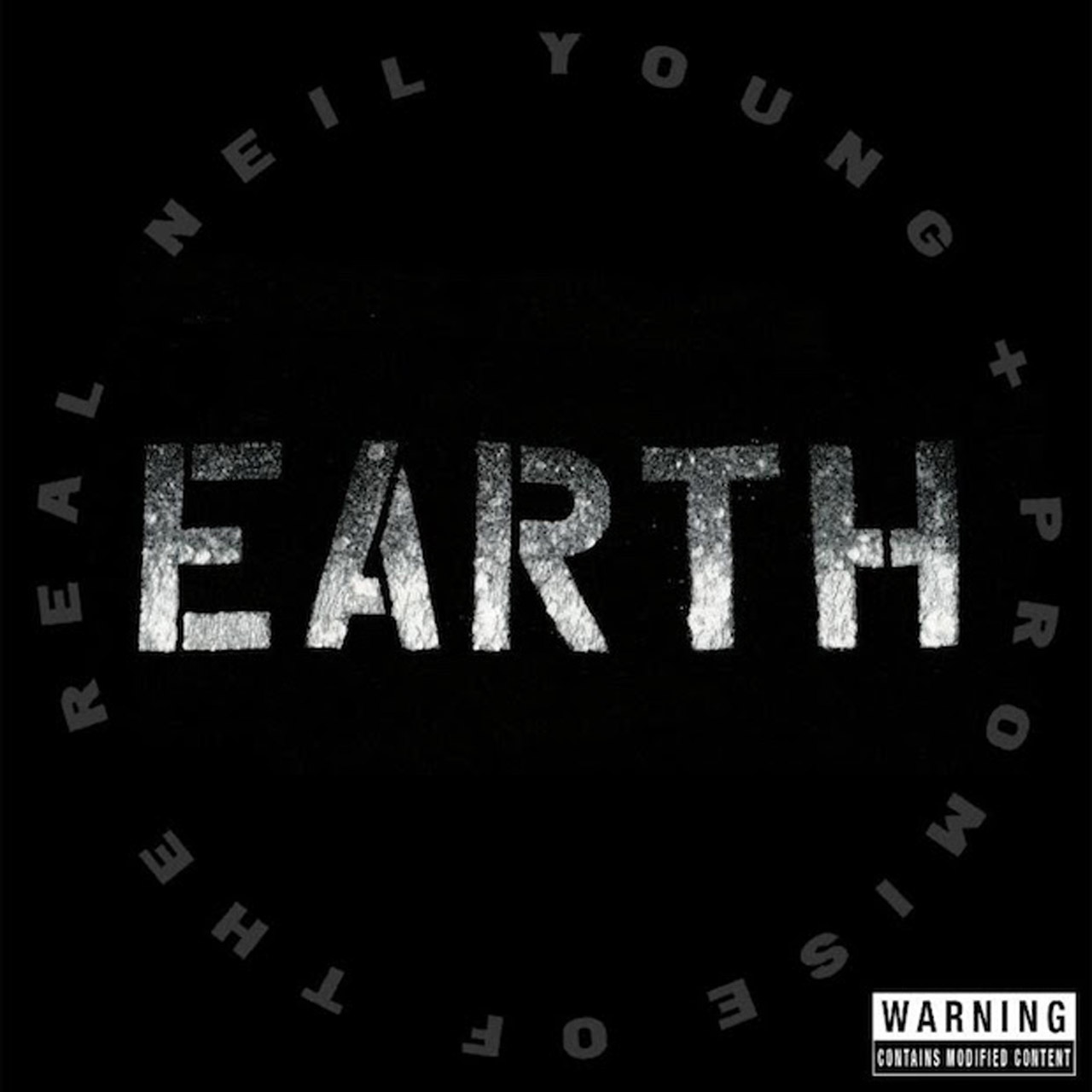

EARTH, Neil Young’s new album with his band Promise of the Real, doesn’t fit in with any other music being produced today. In fact, its single-track, ninety-eight-minute format quite literally doesn’t fit on most standard playback devices, which is why I’m sitting on a couch in Young’s manager’s office in Santa Monica, listening to EARTH on Pono, a high definition audio player of Young’s own conception.

Among the impressive collection of original art and framed prints casually dotting Elliot Roberts’s walls—including sketches by M. C. Escher and René Magritte, paintings by Shepard Fairey, and watercolors by Joni Mitchell—is a personalized message tacked to a piece of foam board that is most revealing of the artist whose career Roberts has managed for nearly half a century. In large type, inscribed by hand to “Elliot” and signed with a simple “Neil,” the note reads:

Just do what you want to do

Don’t listen to anyone else

_____

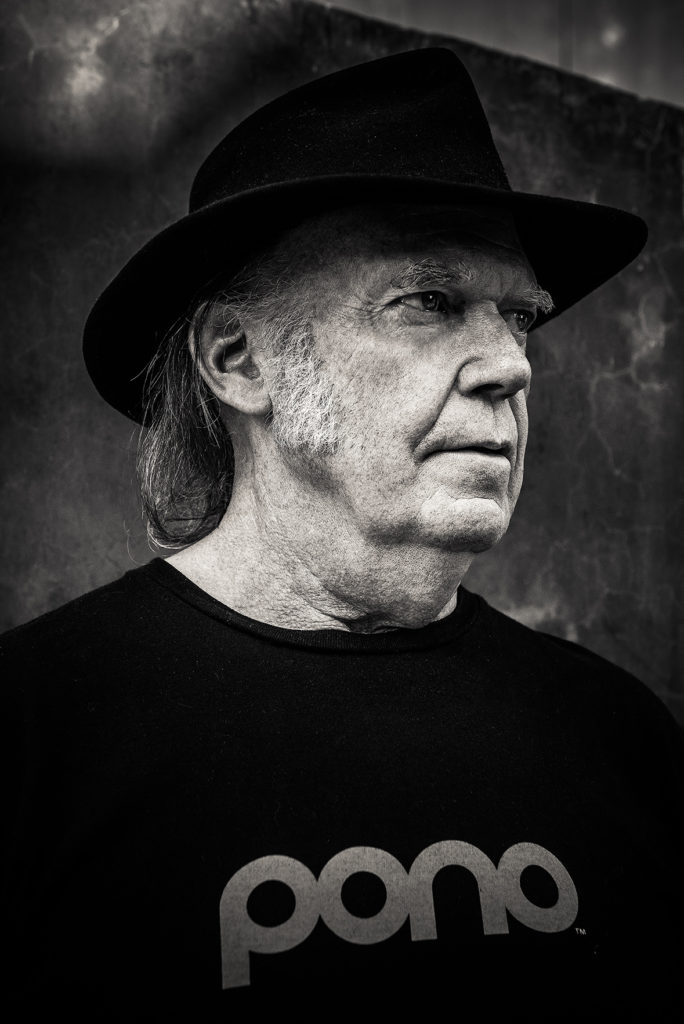

Since bursting onto the scene in the ’60s, Young has become many things: folk pioneer, protest singer, rock innovator, godfather of grunge, book author, toy train–company executive, benefit concert ringmaster, electric-car tinkerer, environmental activist, sound-quality advocate, auteur filmmaker. But no matter what he’s been and what he’s presently doing, it’s undeniable that every second of it has been strictly on Young’s own terms.

EARTH is a live performance epic, a collage recorded on a recent tour spliced together with environmental sounds from field recordings of animals, nature, and humans. The setlist was selected by Young himself from the depths of his own songbook, “songs I have written about living here on our planet together,” he said in a press release, with each track updated and reborn. Classics like “Vampire Blues,” “Human Highway,” and “After the Gold Rush” are here, as are several selections from Ragged Glory, a grip from 2015’s The Monsanto Years, and the previously unreleased “Seed Justice.” “Big Box” rails against big business, name checking Dow Chemical, Exxon, Pfizer, and others as Young blasts lines like “Corporations have feelings, corporations have soul / That’s why they’re like people, just harder to control.” The record ends on a nearly thirty-minute version of “Love and Only Love,” which, naturally, is the album’s first single.

_____

The night after my trip to Roberts’s office, there’s an official listening party for EARTH in the outdoor courtyard of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. The audience is bathed in sound by a Pono loudspeaker system after a brief introduction from the singer himself, who appears on a small stage with no fanfare other than a quick sage-burning purification of the space. “Pono” is the Hawaiian word for “righteous,” and as he speaks, it occurs to me that Young, despite the message written to his manager, does in fact listen to not just anyone but everyone else—he hears the Earth through a righteous ear and sees it through an equally righteous lens. He’s simply learned to filter what he absorbs to create a life that doesn’t fit into any container.

_____

A week later, I’m invited to Roberts’s home in a canyon near Malibu to interview Young. It’s a beautiful day, and I settle in on the ranch-style porch. Each classical element of nature—earth, water, fire, air—is present in all its glory. A stream babbles, stacks of firewood sit in the sun, tall grass blows in a light breeze.

At last, Young joins me in a sitting room under a painting he tells me was made by his daughter. He wears what we’ve come to know as his uniform—a black ball cap, plaid flannel over a t-shirt, baggy pants, walking boots—and speaks comfortably and fluidly about his passions: nature, his new album, Pono, his films and books, political action. Snacking from a bowl of cherries, he laughs loudly and often, seeming ultimately at ease despite the war raging outside.

Do you remember when you first became aware our planet was in trouble?

Do you remember when you first became aware our planet was in trouble?

Neil Young: Hmm…probably in 1970. It was just this kind of creeping awareness. I’d been living in LA for three or four years at that point. When I first got to LA, the air had a smell. There was so much pollution. But I can’t explain it any more than that. The most pollution in any of the places that I’d travelled to at that point in my life was Los Angeles. It took me a while to understand that that wasn’t just something happening here. Over time [my awareness] grew, and it never stopped.

When did you begin to take action regarding environmental issues?

There was an evolution. I changed, and the older I got, the more things mattered. I started thinking about my children’s children, and reading about the trajectory of life and the history of what it’d been like for centuries—what it was like now, and where it was going. If you check things out on a graph, we’re on the end of a hockey stick, and people don’t have a chance because the governments have stacked it all against them feeling it or even knowing it. They know it’s there, but they’re not reminded they can do something about it, except by a few people on the fringe. Nonetheless, [taking action] is still the thing to do and I have a lot of faith in the young people. I just hope they can get things going and that it’s not too late for them.

You see the messages around town: “Save the planet,” “The earth does not belong to man, man belongs to the earth.” How can you encourage action instead of simply raising awareness?

“If I wrote ‘Ohio’ today and put it on the radio, no one would hear it. America is not what it used to be.”

Remember “Earth First!” [the radical environmental activist group formed in 1979]? Earth First! was early. The time when people can understand Earth First! is now. I don’t condone violence and destruction, [but] it’s hard to get people’s attention. The corporations have power, and they control the government. That’s the way our system works, and it’s hard to beat. The media is corporate and the politics are corporate, so we never hear about anything else. If I wrote “Ohio” today and put it on the radio, no one would hear it. America is not what it used to be.

Did you have any trepidation when you wrote “Ohio” for how it could be received, or did you worry about the same for Monsanto Years?

I just write about what I think and what I’m feeling. I’m one person and I just do what I do. If I feared, I didn’t feel it.

Did you feel the flipside of that fear—empowerment?

It’s great to be able to say what’s on your mind, and that’s a part of the way things are supposed to be in my view, and so I do that. And whatever happens because of that will be an illustration of what happens when you do that.

Is that something you learned early on?

I just know that you’ve got to do what you believe in. There’s a bumper sticker that says “Question Authority,” which is a really healthy thing to do. Keep questioning what you hear, what you see. Turn off your TV—burn the fucking TVs. There’s nothing on mainstream corporate television except control of people. Entertainment is like icing on the cake. But really, it’s what’s not on TV, what they keep off of the TV…

I just know that you’ve got to do what you believe in. There’s a bumper sticker that says “Question Authority,” which is a really healthy thing to do. Keep questioning what you hear, what you see. Turn off your TV—burn the fucking TVs. There’s nothing on mainstream corporate television except control of people. Entertainment is like icing on the cake. But really, it’s what’s not on TV, what they keep off of the TV…

In [your 2012 memoir] Waging Heavy Peace, you wrote a passage about walking with your dog and always sending a warning as you walk so as to avoid startling anything you might be approaching. How drastically have we ignored our planet’s warnings? Is that to some degree what EARTH is about?

We don’t even pay attention to what’s going on. We’re so distracted, we don’t see. You can experience the whole [new record] as an ear movie. Close your eyes and listen to it with no stops for an hour and a half. The [message] is that with all the creatures, there’s a relief. There’s no politics with animals, they don’t have an agenda. There’s a war going on and the crickets are still singing. Where they’re allowed to sing, they sing. Every once in a while they get wiped out by what we’re doing, but if they’re not being wiped out, they’re being themselves. They’re not campaigning; they’re living.

Is there an implied chronology to the nature sounds on the record?

One thing leads to another. [The original] running order started with a war, and then there was silence, then nature, and then the record happened. But that just didn’t work for me. So the second running order was this one. It’s all one big song—everything relates to everything else. It was quite a monumental undertaking to put this together. [Neither the co-producer] John Hanlon, who I made the record with, [nor] I had ever worked on anything like it before. It got completely out of control.

Do you mean with making the field recordings?

Field recordings, editing, putting the transitions together, crossfading, going from one place to another, [figuring out] where you introduce the animals [and on] which song. A lot of the field recording I did myself around my home, because my home is surrounded by animals. A crow lives [there], I see the crow every morning, and he has his girlfriend.

Did you tell them they’re guest stars on a Neil Young album?

Yeah! I talk to them all the time, and they talk back. They know me, and they’re not just there, they’re aware; if you pay attention to them, you can see that they’re just as there as you are. My girlfriend has a hummingbird that comes out in the morning and [hovers] right in front of her face and looks at her. It’s interesting; they’re forms of life, and to me it’s a very simple thing: I would like to make sure they have a place to live.

The new song, “Seed Justice,” touches on the battle over commodification of life. Is there a parallel between the seed war and the ownership of creative ideas?

“There’s a war going on and the crickets are still singing.”

Here’s the deal with that. There are ideas that people have, things that they create, and the law of the land says if you patent it, you own it, you get royalties: “it was my idea, I thought of it first.” But we’ve abused the patent system. People use it for control and not what it was originally intended for, just like democracy. The fact is there’s one area not represented by our laws: there’s no representation, protection, or rights given to nature.

We’ll protect Monsanto for taking seeds, which have been a gift from God for centuries. Things that we use for life are now patented and changed, altered in ways that are completely loony that are only for money. And I don’t buy the “we’re feeding the world” bullshit. That’s total crap—we’re not feeding the world, starvation is rampant. If all this was helping, why don’t we see it? I believe that organic agriculture is good because it replenishes the soil, and there’s a balance of nature. You just have to give it room; give it room to grow and it’ll grow. You can’t speed it up, like what Monsanto tries to do, driving things faster and faster.

Sounds a bit like a record label to the artist: “Hurry up and be creative.”

Not all labels. I’ve put out over fifty records, and I’ve never been told by my record label that I had to hurry. Nobody ever said, “Get out there and do something” to me. That’s another thing that happened with the tech revolution—suddenly you don’t need albums anymore: “We got tracks. You can have as many tracks as you want.” They didn’t tell you that less than five percent of the content of the music is in those tracks; you can recognize the songs but that’s not enough. You can recognize the Mona Lisa looking at a Xerox but you can’t feel the beauty of the Mona Lisa.

To that end, what do you need to see happen to be able to deem Pono a success?

To that end, what do you need to see happen to be able to deem Pono a success?

I just want Pono to survive. The longer it lives, the bigger it’ll get. It’s growing slowly. We’re like the Tesla of music. There’s no advertising, we’re just saying, “this is good stuff, this is the way it was made.” Pono only sells the original music with nothing done to it. We have no intellectual property, just quality. And I believe in it.

Did it bring you joy to witness a crowd listening to your music on a Pono system at the recent Natural History Museum event in LA?

Yeah, whether they knew they were listening to [Pono] or not. That’s the only way you can hear EARTH in its entirety; it won’t fit on anything else. CDs, it’s two [discs]; vinyl, it’s six sides.

And was that by design or circumstance?

We made the record the way it was, and it just doesn’t fit. It points out that we’re controlled. Now music doesn’t fit; loose, creative things the artist wants to do don’t fit. It doesn’t fit what’s going on, it doesn’t fit iTunes. When I handed it in, they asked, “What are the tracks?” I said, “Just one ninety-eight-minute track.” And they’re just like, “You’re crazy.”

“We made the record the way it was, and it just doesn’t fit. It points out that we’re controlled. Now music doesn’t fit; loose, creative things the artist wants to do don’t fit.”

We put out “Love and Only Love” as our single—a twenty-nine minute single—on TIDAL, just so people can hear it. TIDAL plays CD quality, it’s a good service, but they’re about to take a dive and go to MQA [Master Quality Authenticated], which is a Warner investment. It’s like to high-res music what the MP3 was to the CD. It just dummies it down, calls it something it isn’t anymore, compresses it, opens it up… It’s people doing the same thing over again. Maybe all the record companies will do it. But I won’t do it. I don’t want to sell that shit, I don’t want to have anything to do with it; if I’m the only one, I don’t care. It just doesn’t matter to me. I can do what I want to do, I’ve got my own player, my own system, I can sell what I want to sell. I’ve earned the right to be able to do that, and that’s what I’m gonna do. People don’t have to buy it.

The one thing I really didn’t anticipate with Pono that I was totally wrong about is that people have invested so much in their MP3 collections that they got pissed off at me—the idea that their stuff is no good. I can’t help it. My [music] was on [MP3] for a long time ’til I realized, “Hey, this is not helping.” I was saying this is OK by doing that, and it’s not OK.

In Waging Heavy Peace, you spoke often about how energizing the process of writing that book was for you, and when you finished the memoir you immediately wrote another one, Special Deluxe. Do you ever feel artistically depleted, or is the cup always full?

It’s a river. It’s not captured in any container. I’m just going with it. I’m seven-eighths [finished with] my third book now, which is science fiction. That’s a whole other world for me, I’ve never done that before. My dad did it—not sci-fi, but my dad wrote novels. This is my first real novel. There are no rules with that.

With all of these different projects, how much do you plan?

I don’t.

If you have a project outlined, you don’t plan?

I don’t have a project outline. Day to day, I have a schedule on a calendar. Well, I try to get them to put my events on a calendar, but it’s very difficult. A calendar’s not understood in my business very well.

You’ve written about seeking closure. But you’re constantly coming up with new projects, so do you feel closure is ever truly an option?

No. I really don’t. I’m sure that it’ll happen. But I don’t have to worry about it, it’s gonna happen without me.

So knowing when a project is complete is just an inherent feeling?

Yeah, I just kind of know it. I can see the end of my book coming now. I never saw it until three or four days ago, so I never planned on how long it was gonna be. But I can see it coming now.

You can always add pages to a book. And now, you can always add minutes to an album. It doesn’t have to fit within the circle.

Yeah! And you don’t have to try to feel what something is and then do it, you can just do what you feel and then see what you’ve made. It’s backwards. Write the script once you know what it was—then you get the script right. FL

This article appears in FLOOD 4. You can download or purchase the magazine here.