Frank Ocean’s unique album rollout strategy (if it can be called that) came to be defined by tantalizingly unmet expectations. People were never exactly patient with the reclusive singer-songwriter—the usual flood of mocking memes hit social media timelines as each rumored release date came and went—but the lengthy gestation period ultimately stoked a state of expectancy that the work itself would thematize.

As a collected body of work, Ocean’s album Blonde, his visual album Endless, and his limited-edition zine Boys Don’t Cry join a conversation that includes two other major releases from high-profile recording artists—Rihanna’s Anti and Kanye West’s The Life of Pablo—that were also unfurled in unconventional, oftentimes frustrating ways. Put up against those 2016 rollouts, however, the resolution of Ocean’s seems tidy: Rihanna, after all, first subjected fans to a largely pointless, months-long global treasure hunt and mobile game that was really just a multimillion-dollar corporate sponsorship launch, and Kanye’s album may still be unfinished (a new track was added to the February release as recently as June). Blonde and Endless both arrived over one weekend, a few weeks following a false-starter live-stream.

All of these peculiar methods of presenting music to listeners speak to a general contention in the recording industry. Amid streaming wars waged by Apple, Spotify, and Tidal, it’s become increasingly unclear how best to go about releasing new music to the world, and so the last decade or so (beginning with Radiohead’s pay-what-you-want In Rainbows) has been one of experimentation at the boundaries of digital media.

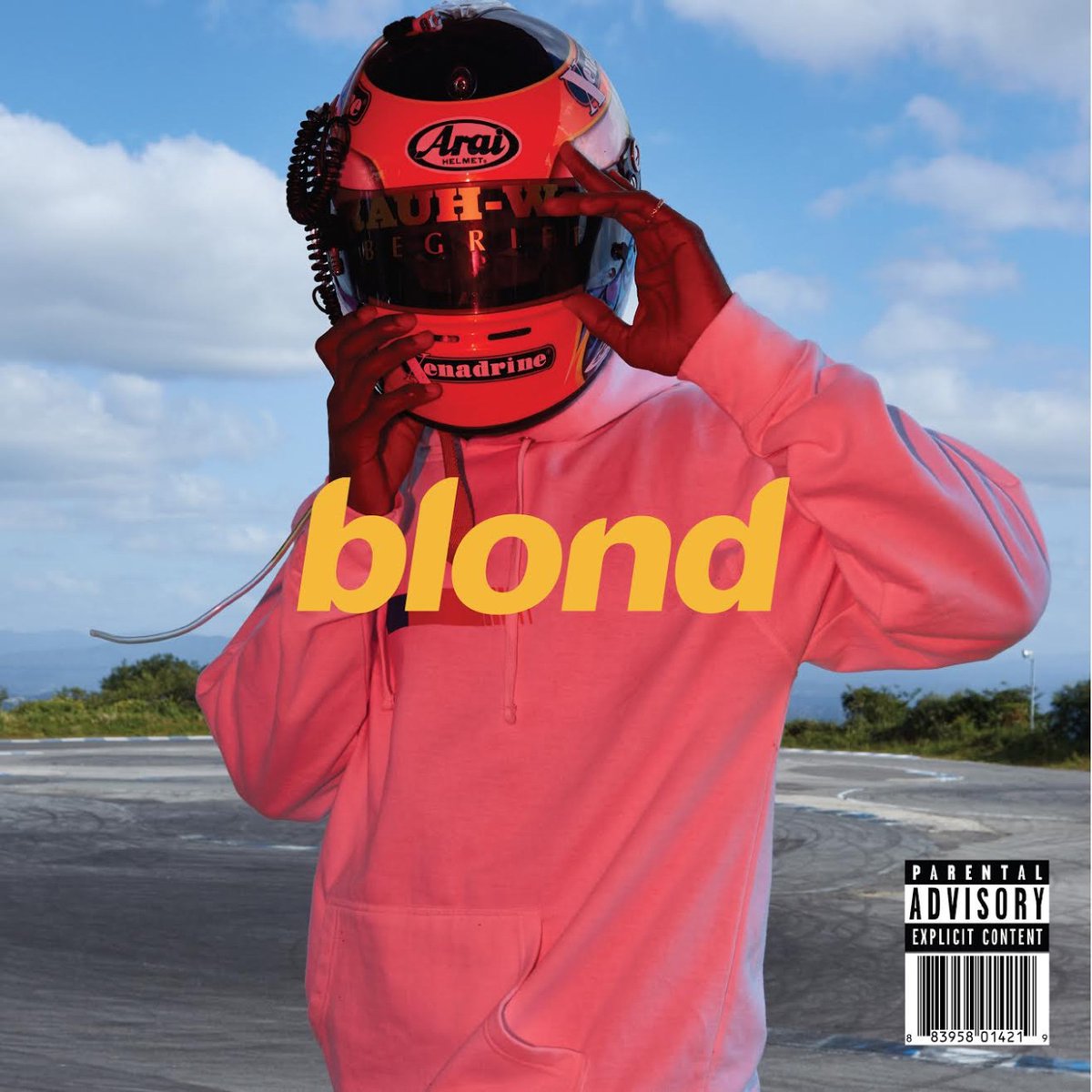

Frank Ocean’s suite of works taps into this too, occupying every space it can—recorded music, film, even physical media. It sounds calculated, and it may well be, but the two satellite efforts arriving with the main attraction—Blonde is technically Ocean’s second official studio album—amplify that work’s affinity for fluid identification. This idea is represented right in the album’s title, printed as the feminine “Blonde” on its Apple Music exclusive release page (and most other promotional material) but as the masculine iteration “Blond” on its official cover art. Ocean has essentially taken the unmet expectations of the last year and responded with a work that subverts and confounds any easy definition one could attempt to assign it.

This lends Blonde, which is generally Ocean’s most diffuse-sounding effort to date, an added weight and purpose each time it chooses to go in directions counter to expectation—it makes self-discovery its aesthetic. That air of experimentation is established early, when Ocean not only slathers autotune all over opener “Nikes” but also chooses to foreground a pitched-up vocal over his own familiar voice. The track circles around themes of self-branding until it lands on a disarming lament, just as the vocal effects are stripped away: “I’m not him, but I’ll mean something to you.”

That line offers a rabbit hole for the rest of Blonde’s arresting contemplation of personal identity, climaxing toward the middle of the album with “Self Control” and its even more devastated confession of emotional surrogacy: “I’ll be the boyfriend in your wet dreams tonight.” The song’s first section boasts Blonde’s most traditional framework—an acoustic blues with a verse/chorus/verse structure—and some of its least coherent imagery (“You cut your hair but you used to live a blonde-ed life”). It also follows a progression similar to that of “Nikes,” slipping from one state of contemplation (jealous frustration) into another (cathartic acceptance).

Again, the voice is crucial—the Frank at the start of “Self Control” is heard nakedly emoting amidst guitar filigrees and haunted, distorted voices burbling in the background, while the contented, or maybe just resigned, finale summons a phalanx of Franks to sing the song’s refrain (“I-I-I / Know you gotta leave-leave-leave”) in perfect unison. It’s one of many examples here of Ocean’s unique gifts as a vocalist, which, true to contemporary production methods, have much more to do with the way he shapes his voice through technology than with his inherent tone and timbre. It’s how he achieves the kinds of expressions an unaffected human voice seems almost incapable of matching.

Again, the voice is crucial—the Frank at the start of “Self Control” is heard nakedly emoting amidst guitar filigrees and haunted, distorted voices burbling in the background, while the contented, or maybe just resigned, finale summons a phalanx of Franks to sing the song’s refrain (“I-I-I / Know you gotta leave-leave-leave”) in perfect unison. It’s one of many examples here of Ocean’s unique gifts as a vocalist, which, true to contemporary production methods, have much more to do with the way he shapes his voice through technology than with his inherent tone and timbre. It’s how he achieves the kinds of expressions an unaffected human voice seems almost incapable of matching.

Blonde relies on shifts in the way Ocean the singer presents himself throughout the course of a song even more than it does the changes in musical arrangement keyed to those vocal parts. The most memorable element of “Ivy,” for instance, isn’t the two-note rhythm guitar figure the song coasts upon for almost its entirety, or the open chords coming to the fore near the end, or even the cacophonous industrial thud that punctuates the track—it’s Ocean’s abrupt pivot from soft coo to pitch-shifted shriek, and the realization of past mistakes that severe mutation evokes.

Ocean’s universally acclaimed 2012 album Channel Orange was more of a spilling-over of ideas sprawled out across a dozen-plus individual miniatures. It was a more-than-impressive showcase for Ocean (and for his one-time right-hand man, producer Malay), but it lacked an overall cohesion of vision. It was far less songful than the singer’s buzzworthy 2011 mixtape Nostalgia, Ultra, too, which mined unexplored melodic and rhythmic potential from often ubiquitous pop hits.

Blonde can claim an even more diminished count of traditionally defined songs than Orange, but it compensates with its own distinct means of structuring. The compositions here can be mapped out by the ways in which Ocean uses his voice, as well as the voices of others. This is true even of interludes like “Be Yourself” (a voicemail from a friend of Ocean’s mom) and “Facebook Story” (a spoken-word anecdote about social media from French DJ SebastiAn).

Endless and Boys Don’t Cry amplify Blonde’s affinity for fluid identification.

This is an album about finding yourself as a constantly evolving project progressing through interpersonal successes and failures, and hearing (if not always accepting) the vocalized wisdom of the people around you. The motherly anti-drug, anti-drinking message on “Be Yourself” is filtered into the following song, “Solo,” which opens with Ocean dropping acid and not apologizing for doing so, but he does eventually contemplate whether the drinking and drugging are true to him or merely a form of protest against the things other people want him to be. It’s one of the few songs here that actually scales back Ocean’s vocal presence by the end, a mirror of its unresolved thematic core.

A balm for these vexing ideas of uncertainty is embedded in Blonde’s final clutch of songs, which settle into a state of recognition that not everything can be planned for. Anxiety, acceptance, and a hefty dose of combative self-confidence all figure into album closer “Futura Free,” which cycles through various vocal inflections and emotional states to match, with Ocean getting personal about demands for his own art (“I ain’t on no schedule”) and letting the mystery be when it comes to the art of others (“They tryna find Tupac / Don’t let ’em find Tupac”). These songs offer a graceful, almost uncharacteristically decisive end point, enriching the tentative gestures of an album that addresses its own expectations and settles for accepting them.

Blonde is indeed the great Frank Ocean album we hoped for—if in ways we might not have expected—but the soundtracked video project Endless achieves its own vitality in part by supplying what its brother/sister album chose not to. It co-opts and provides its own comment on others’ music, featuring a spectral cover of The Isley Brothers’ “At Your Best (You Are Love)” and using a techno song from photographer Wolfgang Tillmans about the possibilities and pratfalls of technology as its bookends. If Blonde is the ghost, the more emotionally haunted work of the two, then Endless is the machine—at its best, it musters indelible, compact compositions of propulsive, dynamic rhythm, zipping by like the product of an efficient assembly line. The fifty-eight frenetic seconds of “Commes des Garçons” and “In Here Somewhere”’s two minutes of cyclical dubstep are the most economical songs Ocean’s recorded since his pre-Nostalgia, Ultra days, kindred to the bootlegged “Pyrite (Fool’s Gold)” and “4 Tears.”

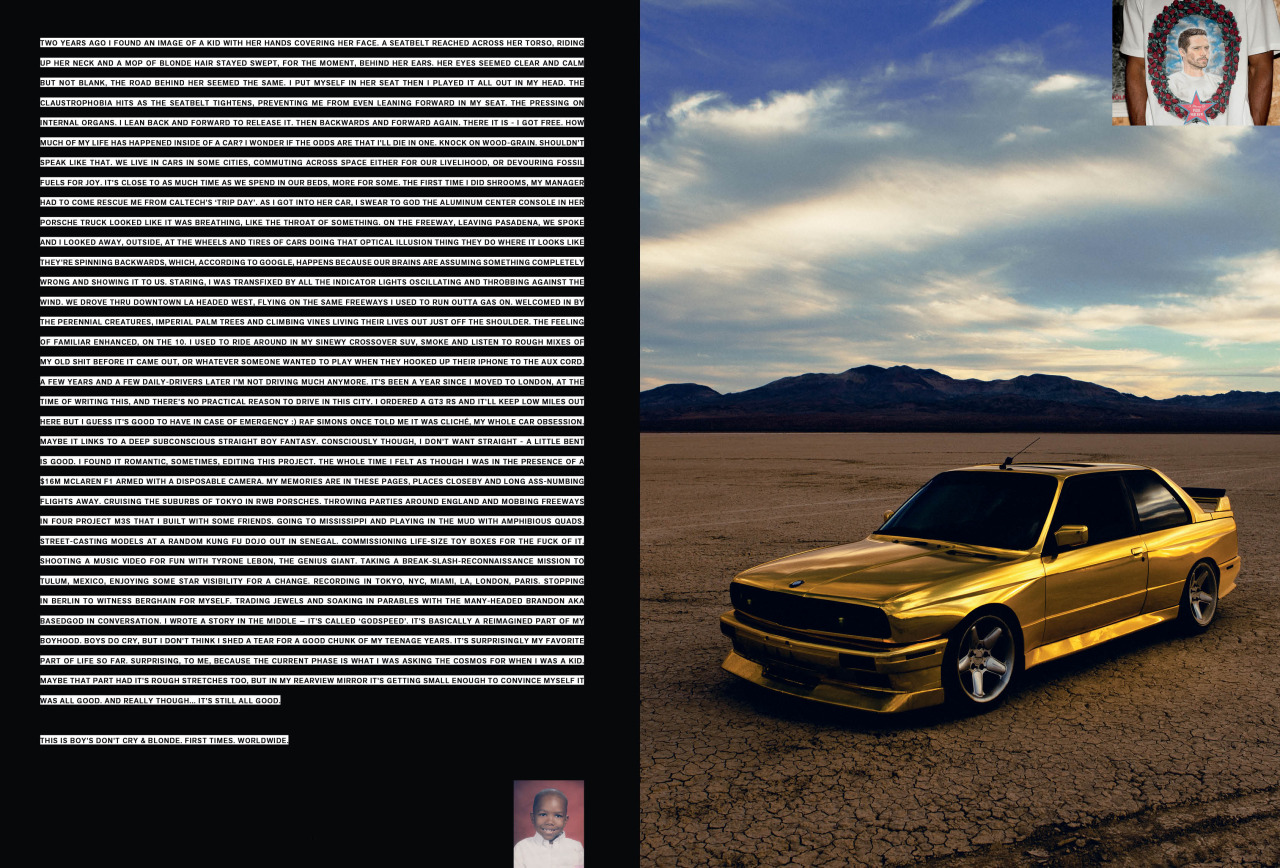

excerpt from Boys Don’t Cry

Neither the precision-manufacturing quality of much of this work nor its handcrafted demo-sounding production aesthetic seem like accidents, as Ocean chose to pair this music with a cleverly edited black-and-white clip of himself patiently and methodically completing a solo carpentry project in a warehouse. And that context proves perfect for adjusting expectations toward a set that may in fact be comprised of Blonde B-sides but comes off as its own fully realized work.

Meanwhile, the Boys Don’t Cry zine—which as of this writing would seem to be inaccessible to anyone who didn’t queue up at release-weekend pop-up shops or subsequently shell out hundreds of bucks for secondhand copies—otherwise seems an extension of the one medium Ocean’s most relied on to shape expectations for his work: his Tumblr. A collection of personal notes, images he likes, and messages from friends and collaborators, it’s his traditionally digital diary breaking from that virtual identity and occupying physical space.

These three works represent a watershed, both in the personal sense and as a confirmation—and nonjudgmental embrace—of the broader recording industry’s ongoing identity crisis. Each progressive piece is worth spending time with, but mainly because Blonde succeeds in its more traditional goal. This whole set is Frank Ocean’s best, most expressive body of music, and it achieves that by finding its own internal logic and playing to no set expectation—except that it be really good. FL