Sage Vaughn was born to a pair of hippies who raised him in Oregon, and later in Los Angeles, the land where the real meets the surreal on a daily basis. Unsurprisingly, the artist—who makes his home in a thriving LA art scene—is constantly exploring the relationship between the world we see and the world we intuit.

As a result, his work challenges the way we perceive the spaces that we live in. Like a paint-smudged Alice falling through the rabbit hole into Wonderland, he illuminates bizarre dreamscapes, places that feel like a kind of hypercolor cousin to our own increasingly bleak reality.

FLOOD caught up with Vaughn at his studio on a bright, clear day to help us find our place in the cosmos. He guided us through his eclectic style and approach, the role surfing plays in his work, and his collaborative work with FLOOD 3 cover artist Michael Muller.

“Eclipse,” 2013

Do you feel like you consciously make the juxtaposition between the real and the surreal when you’re painting a subject? Or is that something that just comes out of it as you develop a subject?

Well, sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. When I first started painting birds, I was just somehow drawn to them. I don’t have any particular affinity toward birds at all, and then I would look back at the work that I did and see, “Oh, it’s mainly these really commonplace birds”; I’m not painting, like, macaws or anything. And then I started looking at these little glimpses of wildlife within our everyday settings, and that started to kind of echo feelings I had about control and chaos and how hard that is to balance.

Speaking of chaos, how do you think the current political climate plays a role in your work?

I oscillate a lot between whether politics is [or is] not the business of artists. In the South American revolutions in the ’60s, there were poets being put to death because of how powerfully their message was lending itself to the movement. And music and stuff was all part of those revolutions, too. I really felt like art didn’t have a part in politics [in the United States]. But then when Shepard Fairey did the piece for Obama, the power behind that was incredible. So I really kinda changed my feelings about it.

I don’t know if my artwork is the most appropriate [way] to address a lot of the political stuff that’s going on right now, [though]. There are a couple of dudes out there that I really respect who are approaching that kind of conversation. As an artist, you’re already making work to be criticized. Then you take it to that level of political discourse, and you’re just like, “Wow.” Those are tough dudes; those are like prizefighter artists.

“Surfing is far more creative than making art.”

You’re an avid surfer and have collaborated with various others who love the water and ocean life. Many surfers say they feel a greater connection to nature and awareness of the world around them. Do you feel that same connection, and do you feel it has an impact on your work?

It’s funny, all the surf paintings I’ve ever done I’ve always just kept for myself; I don’t really like showing those. I think maybe some things have subliminally changed since I started surfing about ten years ago. Most importantly, I just feel like that practice informs my art. It balances things a little bit better. Every day, for the past ten years, [I’ve been] in this room, looking at surfaces close to my face. It’s nice to start the morning looking at the horizon.

Surfing is far more creative than making art. Like, when I watch certain surfers, it’s like the most intuitively creative [movement]—aside from certain kinds of dance—that I’ve ever seen. It’s just instinctual reactions on this flowing [body of water]. And then it’s gone.

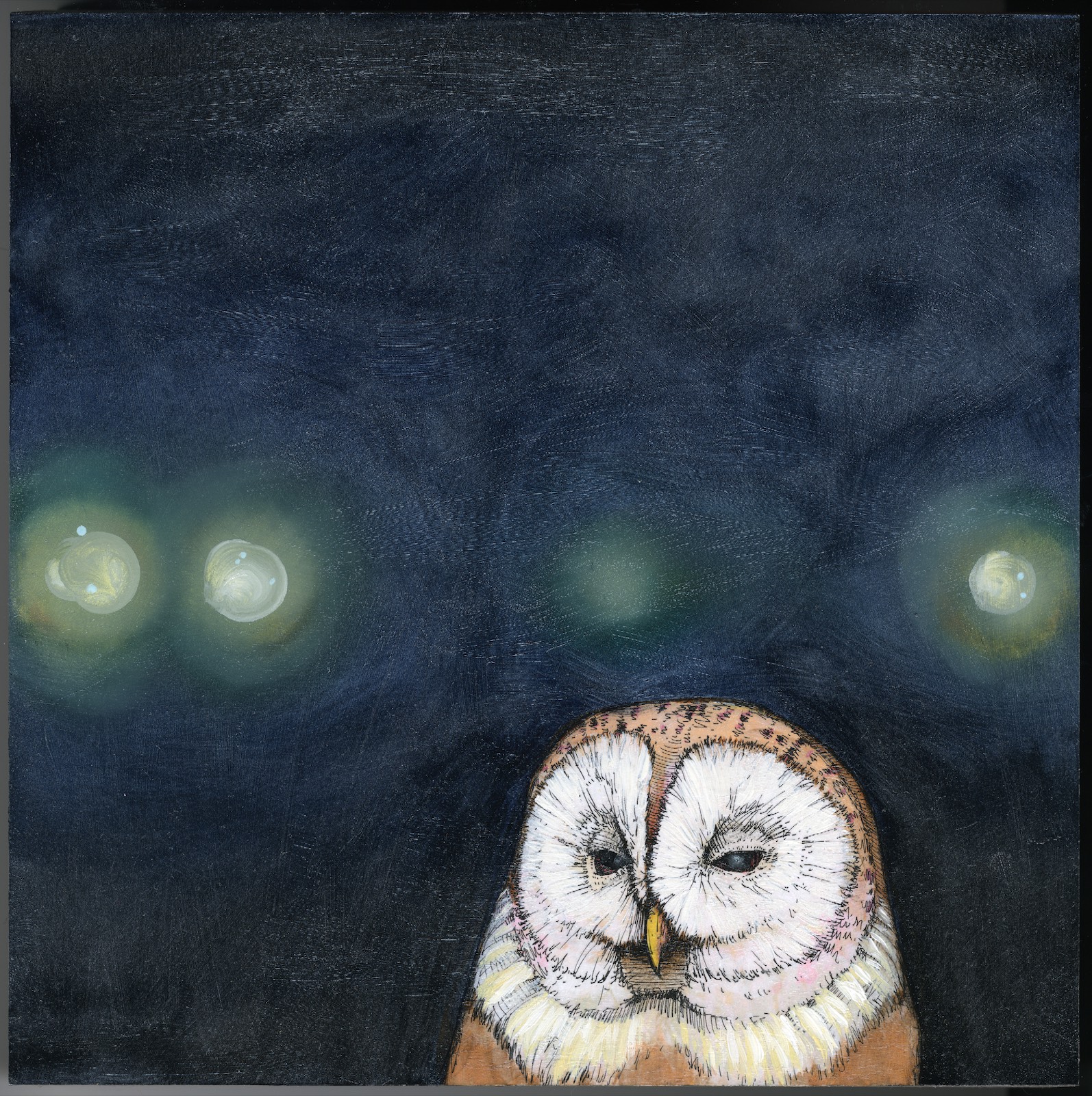

“Stoned Owl,” 2013

Photography plays a huge role in your work, too. What is it about bringing together your painting and real-life images that’s so interesting to you?

When I was painting photo-realistic backgrounds, I just wanted to be able to get as close to a specific [scene] as I could. I would paint these out-of-focus, black-and-whitish–style backgrounds of cities, because I really wanted to give people the feeling of a dream of a city, rather than an illustration of a city. The subjects—the butterflies and the birds—were so specific and illustrative that I wanted the idea of a setting, as opposed to “New York City” or whatever.

And that just kind of worked. Luckily, it’s worked out pretty well with the guys I’ve collaborated with. But it’s a funny [mode of] collaboration. Like working with Michael Muller, I know that dude shoots huge campaigns where there’s so many people in the room with him as he’s clicking and taking, like, fifteen-hundred shots with the agents and everyone there. And then we work on something together, and I’m like, “Dude, you realize it’s just me in a room making all the decisions?” And we just make one picture when it’s done. It’s such a different balance.

You’ve been working with Muller for five or six years. How did those collaborations come about?

We were surfing together with a mutual friend, and my friend was like, “Have you ever seen Mike’s shark photos?” And Mike was like, “Yeah, I’ve been doing these Great White shark photos and I’m gonna have all these other artists paint on them.” He sent me one, and I just had an idea—like, I saw it finished before it had even started. He had already done so much of the work that I could just kind of [do my thing]. Most of my paintings take a long time, so this was a nice one. He didn’t do too many other collaborations after that, which I felt pretty cocky about afterwards [laughs].

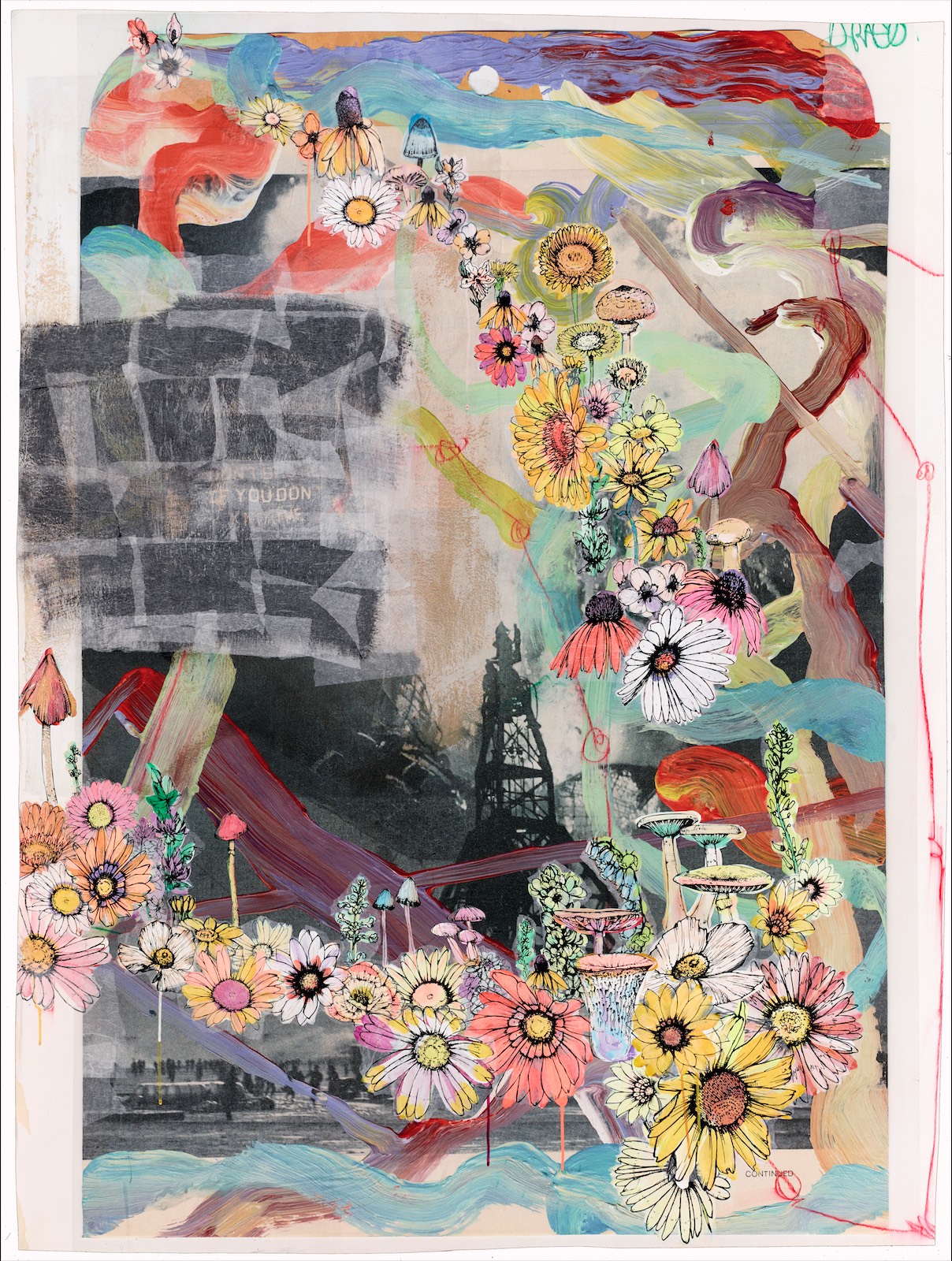

“Draco,” 2015

You’ve also collaborated and shown work with surfer Rob Machado. How did that process differ?

That was a cumulative process. Rob was shaping surfboards, and I said to him something about how I should paint on one of those. He shaped a board for his wife and one for me and one for himself, and I painted on [all three]. Then I told him that we should do a show of these, because they came out pretty good right from the beginning. So we did a show and ran it through his charity. I like his charity; it’s a really reasonable charity and really focused. It’s really simple—[they’re like,] “We’re making money to pick trash up off of beaches,” so it was easy to do.

Are there any big projects you’re working on that you’re excited about?

I just did a bunch of paintings, like big mural pieces, at the Annapurna Pictures production offices, which was great because that area they own has a really amazing artistic history. It was [first the home of] these silent film actresses that then made the first female film studio, and then it was the Margo Leavin Gallery, which was a super-rad gallery run by a rad lady that showed all the top-notch artists, but in this really laid-back setting. LA was not the fuckin’ center of the art world for so long, and she would do a David Hockney show there [when no one else would]. So the place has a lot of good history, and I was stoked that they asked me to do something there.

I’m also doing something with the University of Oregon—these big sculptures at this new stadium they built. It’s a cool public art piece that is really far out of my comfort zone in terms of what I’m good at doing—by that I mean the logistics of it are something I’m not good at doing. The art’s gonna be good! But the rest of it, well… I’m definitely working with people who are incredibly patient and nice to me.

“Culture Club,” 2017

There’s often a misconception that artists lack discipline, but you are extremely prolific. Describe what your principal motivators are and where you think your strong work ethic comes from.

I love the doing, I love the making. I love the—well, I don’t like the end result. I don’t want to own anything really, just the making of it is what I love. It’s really selfish, but I’ve somehow managed to make my life into the thing where I just get to keep doing that part that I like.

So I [just kind of] ended up with this work ethic. I mean, I think I was also avoiding a lot of weird deep personal shit by just locking myself away in my studio for a number of years [laughs]. But it worked!

How do you see your own art evolving over time and with age?

I think it’s gettin’ weirder. I didn’t expect it to. There are certain weird tropes that artists have that I’ve always tried my hardest to avoid. It’s like becoming your parents: You’re working so hard to not become just like your parents, and then you go this whole around-the-world way to being just like your dad. You’re like, “Oh, fuck. I was avoiding that one thing he does, and I came around here and did all these fifty other things that he does.”

“I could paint the same painting now that I’ll probably paint in fifty years, but I wouldn’t like it now.”

There are certain artists that I’ve seen… It’s hard to describe, but artists don’t get tighter and tighter as they get older. They tend to find essence. Instead of boiling things down, they loosen things up, they become less finicky. You look at Jasper Johns, and over his career, toward the end—not the end, but the later years—it’s just getting less and less finicky and less and less tight. I find myself doing that, but by millimeters, where I’m not spending as much time fussing over things, and it’s nice. So I think it’s gonna get pretty loose and messy in the end.

But you’re comfortable with that.

Yes. I mean, I’m working on it. I think the thing is me getting comfortable with it, if that makes sense. I could paint the same painting now that I’ll probably paint in fifty years, but I wouldn’t like it now. Fifty years from now, I’ll be like, “No, that’s what it is.” [Laughs.]

You’ve travelled the world showing your work, including stints in Europe and China. Is there anywhere you would love to go to work?

There are a couple of weird spots in the world I’ve never been to that I feel like would be good places to make work, and I don’t know why. I have all these things—rules, invisible rules—inside of me that I gave myself about how to make work. I’ll be painting something, and I’ll be like, “That’s not the right color.” But then I went to Mexico, and I went surfing, and I was going through the jungle and looking at some of the colors in the leaves there, and I thought, “So you could do that. You can do red, yellow, and green in the leaf. That’s totally cool.”

So I think certain places would allow me to give myself permission to do certain things that I think would be good. It’s usually the surf travel that gives me more inspiration. The art travels are always to a place that’s not inspiring—London or Geneva, or some place that you think, “It’s cool to be here, it’s awesome, but it’s not making me want to work.” But then I go to, like, Costa Rica, and I’m like, “Oh, yeah, that’s fuckin’ weird, we should paint things that look like that.”

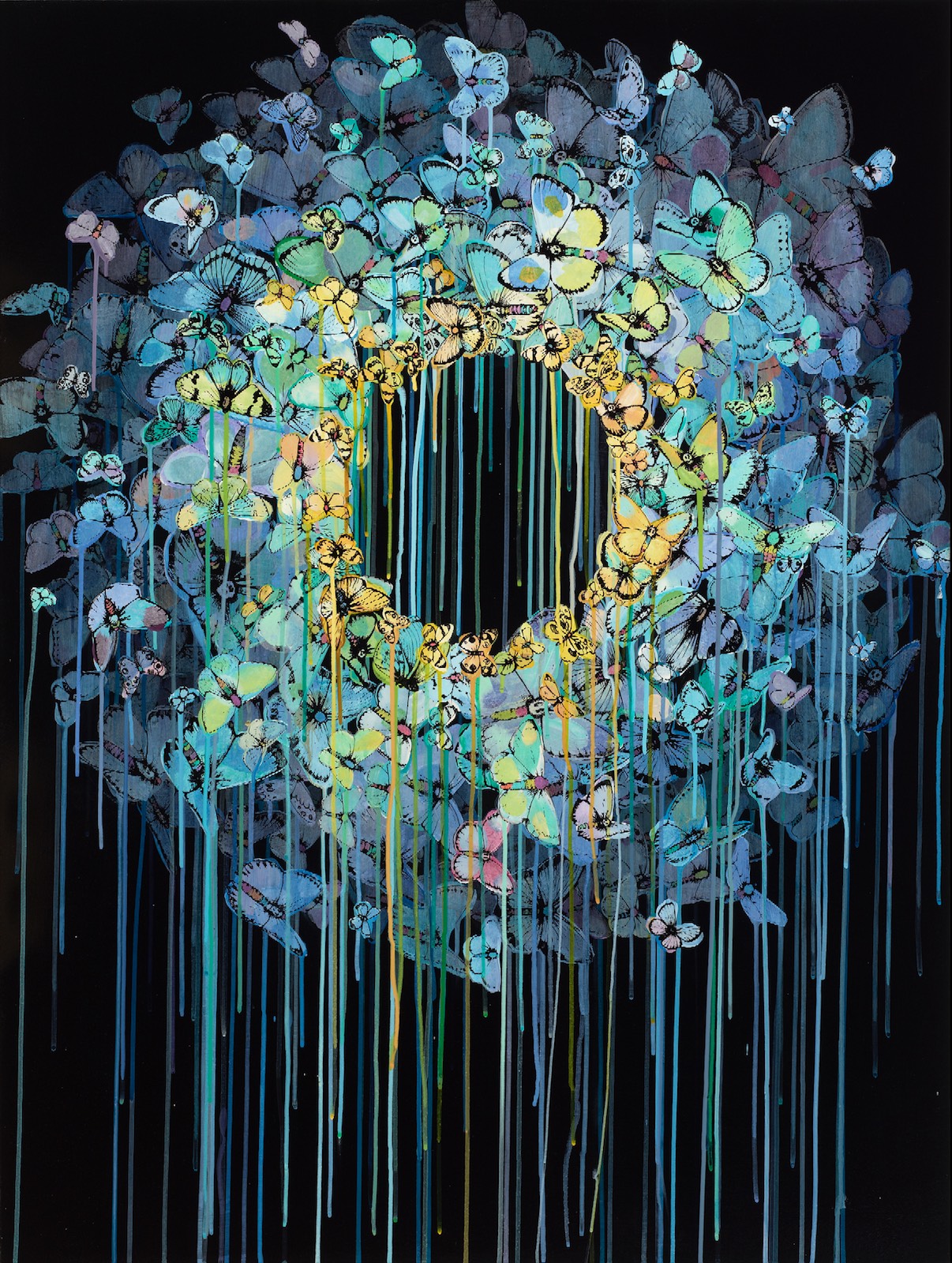

“Ring Cycle (Kissing to Be Clever),” 2013

Let’s talk about music. What do you typically listen to when you work? And does that differ from what you’re listening to when you’re not working?

I think I’ve listened to everything. I’ve spent so much time in the studio just listening to music [laughs]. I don’t think I’ve really listened to music in here in a long time, though. Now I mainly listen to podcasts and books on tape. To be honest, music-wise, I’ve listened to nothing but Steely Dan for the past three months. Like, a lot of it. [Editor’s note: This interview was conducted before Steely Dan’s Walter Becker passed away.]

If you had to compare your overall body of work to one album, what would it be?

I’ll just go with my first thing that comes to mind: Money Mark’s first album, Mark’s Keyboard Repair. I’ve always wanted to be part of some art movement or piece with a clique of other artists, but looking back, I never was. And I think Mark’s first album was like that, where it was just a fucking beauty, an amazing thing that just stood outside of everything.

“Against the Common Good”

Who are some up-and-coming LA artists that you’re a fan of?

There’s a lot of cool shit going on right now, a lot of younger dudes and ladies making work with a kind of courage that wasn’t happening when I first started. There weren’t that many dudes making art in LA when I started making art. I wasn’t ahead of the curve or anything; it just wasn’t a thing then. Now I think it’s been kind of formulaic for long enough and there’s a bunch of people doing some pretty far-out stuff that’s very different.

My friend Thomas Lynch does these amazing, super-trippy paintings that are gorgeous. He’s going for it in a big way—a very specific, airbrushed, surfy skeleton galactic kinda way. It’s making me really recognize how beautiful that stuff is. And his brother, Brendan, is doing these cool, like, Dungeons & Dragons style paintings that you’re like, “Oh, yeah, I kinda love that stuff. Oh, fuck, you’re totally making me realize how rad dragons are!” [Laughs.]

Famous last words?

“Dangit.” Oh, or, “I should have probably thought about this.” That should be my famous last words. FL

This article appears in FLOOD 7. You can download or purchase the magazine here.