The etymology of the word “shark” is a little hazy but its intended meaning has always been clear. Some accounts attribute the term in origin to the Mayans and some to a published British work from the 1600s, but most will agree that, semantically, the word is derived from some variation of malicious descriptions like these: “a dishonest person who preys on others,” “voracious or predatory persons,” “artful swindlers,” “exploiters,” the German word for “scoundrel,” and so on and so on. It seems we never gave the poor animal a chance.

Sharks have always inspired fear in humans, and today’s media has done much to encourage this fright. From Jaws to Shark Week to our habit of lending the term to any unsavory person or activity—card sharks, loan sharks, even a disgustingly perverted public-shaming trend called “sharking”—these ancient beasts of the sea have a long swim upstream ahead of them in the eyes of society.

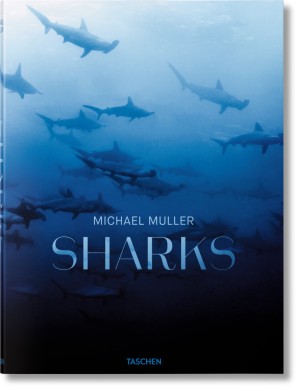

Michael Muller wants to change this perception. About ten years ago, the famed Hollywood photographer—known for his world-class pictures of A-list celebrities, blockbuster comic book movie campaigns, advertisements, album covers, short films, commercial work, fine-art collaborations, and even his own photo app—fell in love with photographing sharks while on a dive with Great Whites as a tourist in Mexico. Working tirelessly and without fear over the past decade, Muller and his intrepid crew quickly developed both a new concept for capturing images of the elusive animals and also the technical equipment needed to bring that vision to life.

“I’m always wanting to work in a fresh way that hasn’t been seen before,” Muller says. “I wanted to bring a Great White into my studio, so to speak, and light it just like I do my superhero shots or my really stylized portraiture. So, since I couldn’t bring a shark into the studio without it being dead, I realized I’d have to bring the studio to the shark.” Working to concept and commission a studio-quality, high-powered underwater lighting rig, Muller found success after myriad tests and prototypes, and today his patented creation has accompanied him and his team on dozens of cageless dive shoots in exotic waters and shark habitats around the world.

The resulting photographs captured by Muller are like no underwater images ever seen before, and they are documented in his forthcoming book, Sharks: Face-to-Face with the Ocean’s Endangered Predator. Complete with essays and assistance from conservationists, marine researchers, and even Philippe Cousteau, Jr. (the grandson of underwater explorer Jacques Cousteau), the TASCHEN book is extraordinary not only in its aesthetic wonder but also in its ability to change and inspire the way we see—and think about—these majestic creatures of the deep.

For Muller—a lifelong adventurer who grew up in California and Saudi Arabia, where he learned the joys of diving, travel, and surfing, and whose early snowboarding photography set him on his career path—his art is about overcoming all preconceived notions of fear in an effort to educate and open minds to shark conservation and protection. While global statistics tell us that there are only five fatal shark attacks on humans per year, the scope of the animals’ widespread mistreatment and slaughter is largely unknown to the general public.

For Muller—a lifelong adventurer who grew up in California and Saudi Arabia, where he learned the joys of diving, travel, and surfing, and whose early snowboarding photography set him on his career path—his art is about overcoming all preconceived notions of fear in an effort to educate and open minds to shark conservation and protection. While global statistics tell us that there are only five fatal shark attacks on humans per year, the scope of the animals’ widespread mistreatment and slaughter is largely unknown to the general public.

“Every year an estimated 100 million sharks are killed by humans across the globe for their meat, fins, liver, or gill rakers, generating an estimated $630 million in sales,” writes Dr. Alison Kock, a South African marine biologist and research manager at Shark Spotters. That organization—as well as Muller’s mentor Morne Hardenberg’s group Shark Explorers, Cousteau Jr.’s EarthEcho International, Muller’s own White Mike campaign, and others—are making it their mission to expand our shark conservation awareness and action. Yet, sadly, with the growing threats of climate change, overfishing, and pollution in addition to the shark finning trade, it’s proving to be an upstream swim for all of us.

“Since I couldn’t bring a shark into the studio without it being dead, I realized I’d have to bring the studio to the shark.”

Still, Muller’s superhuman efforts to create superhero-worthy images of sharks are casting the creatures in a whole new light. In addition to his book, he is at work on a full-length documentary about sharks, while also gathering information and resources on a new wild animal subject to begin shooting in the coming months. For Muller, his work is more than a hobby or even a profession: it’s his duty.

“By going out into nature over the span of ten years, I have a pretty fresh perspective on how bad of a space we are really getting ourselves into, which was the motivation for the book I made,” he says. “I said to myself, ‘I don’t think my daughters are going to be able to see some of the things I’m seeing. So I’m going to do what I can about it.’ I have a gift for photography—I’ve sold Nike shoes, and the films I’ve shot movie posters for have generated billions of dollars—so now maybe I can sell these animals in a way that people haven’t seen before and educate them on what’s happening.”

Here, FLOOD speaks with White Mike himself about facing fears, diving deep, and getting his shot.

Michael Muller photographed by Morne Hardenberg

Looking at your Sharks book, I’m reminded of the line Brad Pitt says to Kevin Spacey in the movie Seven: “When a person is insane, as you clearly are, do you know that you’re insane?”

Michael Muller: [Laughs.] Well, that’s all in the eye of the beholder now, isn’t it? The same person probably looks at you, or Brad Pitt, and thinks you’re both insane.

Touché. But seriously, just how dangerous is it down there?

Well, that’s the whole point of the book: to show that it’s not dangerous. You, me, everyone else, we’ve been programmed by the media and by movies; this animal has been demonized. I was scared shitless of sharks and I would’ve said the exact same thing you did, until I went in the water and experienced these animals and had that shift myself.

The minute you’re in the water and see them, your whole mindset changes. You realize how smart they are and how they’re more scared of us than we are of them. That’s why there are only five deadly shark attacks per year around the world. Obviously, swimming with a Great White out of a cage takes experience on a different level, but for the most part they’re not really after us. We’re not on their menu; they’re really only after the fish we’re feeding them. Still, they are wild animals so don’t think for a second I am encouraging everyone to go swim with sharks. It has taken years and hundreds of hours for me to learn how to carry myself on a dive and even then I always go with my shark experts who have my back and I have theirs. The minute you get cocky and think you got this is the minute you’re going to find yourself in hot water. Humility is a must when swimming with these predators.

You studied up and prepared yourself as much as possible, but what were you feeling on your first dives, both in and out of the cage?

The first trip I went on was with Great Whites. I was in the cage, but I wanted to be out. My second trip was to the Galápagos [Islands] and there were no cages at all. There was definitely adrenaline—and a little bit of fear—when I was getting circled by the sharks, because at that point I didn’t have the experience and the time in the water with these animals to know that I really had nothing to worry about. It takes time learning their behavior and getting comfortable, but that fear came up and I faced it and it went away.

Can you describe how a shark moves in the water as seen from your unique vantage point?

You’ve got different species and you’ve got different personalities, so each shark is a little bit different. You can learn their body language. It’s just like with people: You can tell a pissed off shark or an aggressive shark compared to a mellow one just by their body language and the way their fins are dropped, the way they’re moving around, if they’re circling, etcetera.

I can’t expect that you’re able to direct a shark, but are you looking for a certain movement or appearance in your subjects underwater to get the shot? Can you tell, in the moment, when it worked?

“It’s like an SUV-and-a-half with teeth going by you. It’s hard to explain.”

Yes and no. I cannot direct a shark. I can control the shark [to some degree by] having food and drawing it in with fish, but that’s about it. The rest is timing, getting yourself in the right position, and knowing their behavior to know what the shark’s going to do. I don’t spend a lot of time down there reviewing my shots. One of the great things about doing this is that it’s the closest to “in the moment” I’ve ever felt. You’re really there and it’s so quiet. Once I get the light and the aperture dialed in, I just shoot. But there are definitely moments where I’m like, “I think I nailed that.”

What is the size-and-speed scale like when you’re swimming with larger sharks? Is it even possible to fully comprehend just how big and fast they are?

That first trip with Great Whites, a shark went by the cage and in my head I thought he was going around the cage’s back. Before the thought was even finished the thing was right back in front of me. It showed me how powerful and fast that seventeen-foot shark was. It blew my mind.

You really get a sense of their size when you’re underneath them and they swim over the top of you, and you see their girth and the belly and the thickness. It’s like an SUV-and-a-half with teeth going by you. It’s hard to explain. When you swim without a cage, you’ve got to swim directly at a shark. Your mind is telling you to swim the other way, but [doing that you would] become prey instead of the predator. It goes against your make-up.

Michael Muller photographed by Marc Lemoine

See? “When a person is insane…” So now, looking back on your own life, can you identify what made you into the person who can keep cool in an environment like that?

I think it’s a sum of all my experiences in life. From putting my body through what I did with snowboarding, traversing steep crevices in Europe, and triathlons, to living in Harlem in the ’90s and being the only white guy there—[hence] “White Mike”—I’ve been in a lot of rough neighborhoods. Fear is something you’ve got to face. People and animals will smell it on you. I’m not one to be timid, and that’s what got me on that first shark trip. And, like the acronym goes, “False Evidence Appearing Real”: it’s so true with sharks. There’s a bunch of false evidence that seems real until you see it.

What have you learned from shooting sharks that you can bring to the other parts of your photography career?

Patience—a lot of patience. There’s a lot of time spent at sea waiting for the animal. You’ve always got to be ready and prepared. Sometimes in the studio [a subject] will do something and if your finger isn’t on the button and you’re not ready, you’ll miss the shot. You’ll miss the moment. So, it’s good training for that. But when you’re sitting underwater while a big SUV with teeth goes by, it’s hard to get impressed by any human. It sort of keeps me in that headspace, too, which I think is always good.

I’d imagine it’s a feeling you don’t necessarily get from seeing your photographs in a book or on a billboard.

Early on, I was guilty of wanting [people] to respect me by having that billboard or shooting that album cover, and I learned quickly that if you go for that, it’s never enough. It’s a god-shaped hole and no book, no photo, no album will fill it. And believe me, I tried for years. I know it sounds so new-agey but the fact is that truth has been around since the beginning of time. You can’t look to those things to make you or to define you. Even this book doesn’t define me. It’s a diary of a portion of my life.

But [photographing sharks] is something I’m very passionate about. I love those creatures. I love our planet. I love my kids, and I want them to see what’s on our planet. Our species is doing a lot of damage to it, so I felt the responsibility to take my gift of photography [and share]. People always ask Paul Watson, the Greenpeace founder who started Sea Shepherd [Conservation Society], “What are you gonna do about this?” And he always says, “What are you gonna do about it?” That has always resonated with me. So I think at that moment, I said, “What am I gonna do? I’m gonna take photos.” And that’s what I’ve done and what I’ll continue to do. FL

This article appears in FLOOD 3. You can download or purchase the magazine here.