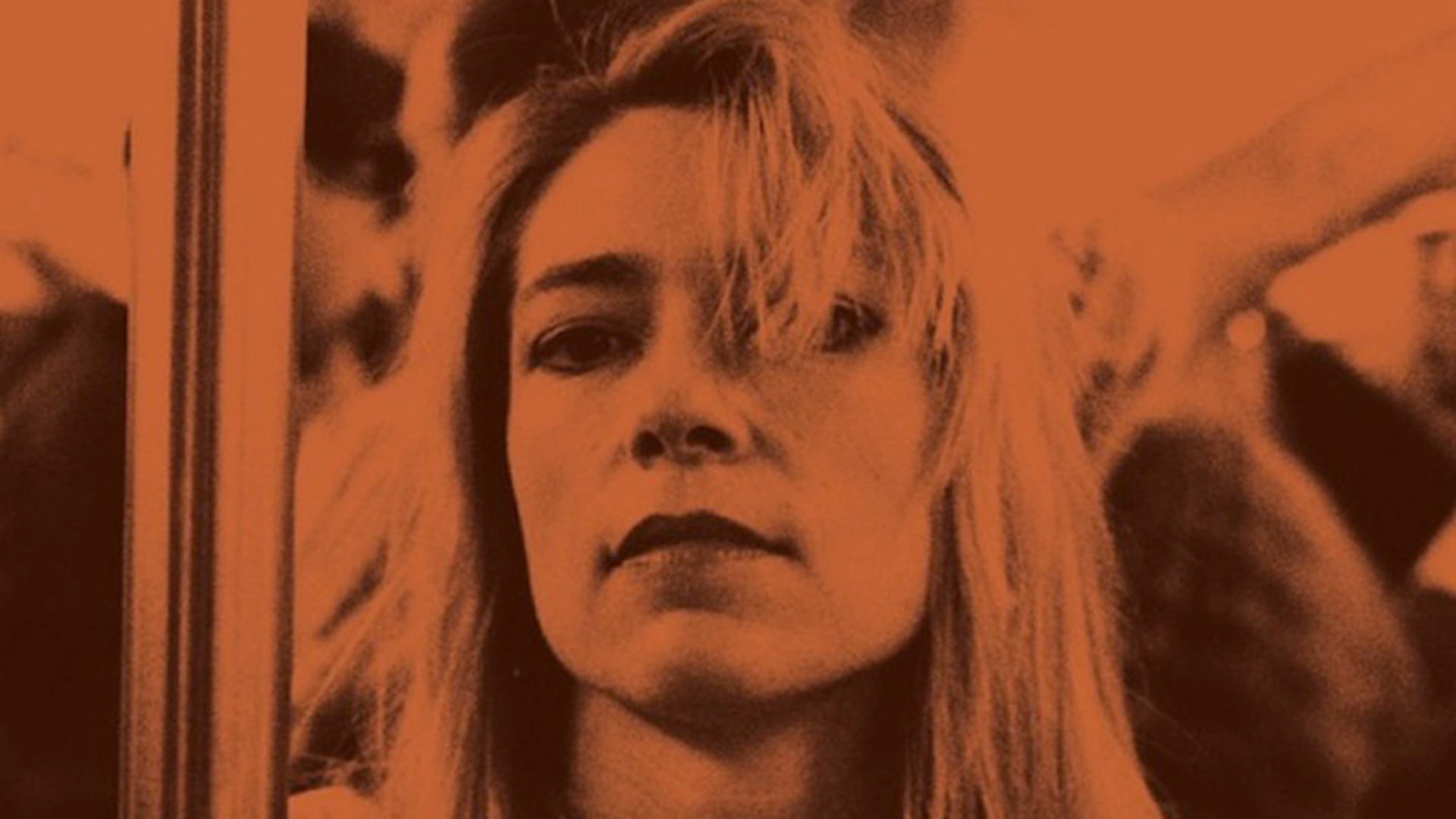

Inspired by Kim Gordon’s letter to Karen Carpenter, republished and discussed in Gordon’s new memoir Girl in a Band, here Carrie Tucker writes her own letter, from a fan to an idol.

Dear Kim,

When I was nineteen, I worked as a receptionist in the wasteland of Santa Fe Springs, California, answering phones for someone else in an office full of scumbags. Like the much older director of sales who, upon finding out I liked to write, said, “I’m a writer, too! Let me show you one of my pieces!” He brought it in the next day. It was soft porn with thinly disguised characters: him as subject, me as object.

I drove home, feeling as filthy and hopeless as the industrial landscape, Dirty on repeat. “Swimsuit Issue” in particular. “I’m just here for dictation,” you chanted the names of swimsuit models, ending with the lyrics “I’m swimming”? Or was it, “Us women”? I was sure it was the latter. And I felt solidarity with you and the women you supported, like Julia Cafritz and Kathleen Hanna. The music world was an oyster and you all were its rough-edged pearls, the swaggering girls reclaiming insulting terms, turning the words around on their male creators. You were a girl in a band. You could handle this. You would have left the sales guy shaking.

The vulnerability in your memoir took me by pleasant surprise. I don’t know what I was expecting—that you were impervious to insecurity? You always seemed like it, but you knew how you were perceived: aloof, impossibly cool, untouchable. It was painful to read the opening of your book: the ending of a lifelong relationship between Sonic Youth and the audience, the ending of a marriage in tragic detail. Poetic to start from the end and work forward, really. “Here’s my pain: take it, absorb it, deflect it, change it.”

Your internal world and your external image are dissonant, like your music, and I wish I knew when I was nineteen what I know since reading your book: that, no matter what a thing looks like on the outside, its inside can be soft and fleshy, either ripe or spoiling. That what drove you to join a band—the act of male bonding onstage, the need to be “inside that male dynamic, not staring in through a closed window”—was a need other people had, too. That sincerity didn’t have to be dead. That vulnerability wasn’t an embarassment, modesty, nor a joke. The term “girl in a band” is such a tongue-in-cheek minimization of your power.

Which is why the current press narrative of Girl in a Band pisses me off—highlighting tidbits about Kurt and Courtney, mental illness, and your marriage. While they are important strands of your story, they’re pulled out of context and crudely braided together for page views. Much of this narrative has been written by men.

And speaking of men: I went to see Thurston speak at a book festival not long after the announcement of your divorce. I have a certain resistance to reading about the inner workings of my idols’ personal lives, so I had no idea—nor should I have—of the cause of your marriage’s dissolution, his banal American male midlife crisis: ageing ego, younger woman. My presence at that talk makes me uncomfortable now. “Teen Age Riot” may recall a time that was both terrifying and liberating, but in his own words: he acts the hero, we paint a zero on his hand.

If I ever have a daughter, I will give her your book to remind her that she controls her own narrative.

Your fan,

Carrie

Kim Gordon will be exhibiting her artwork at the 303 Gallery in NYC June 4 through July 25, 2015. Her memoir Girl in a Band is out now on Dey Street Books/HarperCollins.