Spend some time with Rob Sevier and Ken Shipley. Then watch as your understanding of what constitutes the great rock-and-roll canon deepens, expands, and grows to the point of bafflement. With the intermixed passion and familiarity of undergrads arguing about Bowie, the two founders of The Numero Group—a collection of labels that specialize in reissues, frequently of music that never saw release beyond a few dozen copies—reference and reframe artists for whom the term “obscurity” would be a compliment.

But “obscurity” isn’t the right word, really, since it implies a kind of tabulation system that assigns value and weight based on what’s known; calling the artists that Sevier and Shipley have introduced to the moderately wider world “obscure” is to accuse them of failing at a game that they were never playing to begin with. From most vantage points, they’re simply more-distant stars in a broad cosmos, stars that seem to grow larger and brighter with the right conditions. And like most heavenly bodies, they sometimes connect to form a unique outline of a familiar figure; see 2013’s incredible Purple Snow, their four-LP portrait of the Minneapolis scene that gave rise to Prince, for a prime example.

Over the course of our conversation, it becomes apparent that the duo do what they do—tracking down old master tapes, spending hours on the phone trying to make contact with musicians who long ago lost interest in music, frantically chasing down rumors about records that may only exist in an engineer’s handwritten notes—because the music made by Francis Reneau & The Mission Singers, say, matters to them for the same reason that The Staple Singers matter to so many others. Because they all made earth-moving music.

Ken, you were working for Rykodisc when you guys got started. Rob, what were you doing when you first starting talking about this idea?

Ken, you were working for Rykodisc when you guys got started. Rob, what were you doing when you first starting talking about this idea?

Rob Sevier: My day job was working in record distribution. I was earnestly collecting free jazz and American soul music, and I dabbled in a few other things. I think I had some acid folk LPs. I’d tracked a few artists and talked to a few artists—just about their music. I had no real scheme for it.

Ken Shipley: There were these really fascinating threads that Rob was tugging at really early, and in a way we just found a great way to organize a bunch of ideas really quickly. So we’d say, “We want to do the definitive x, or we want to make this thing.”

What does the process of starting a new record look like? Do you set out to make a new Eccentric Soul record, for example, or are you always listening and earmarking things?

Sevier: A lot of these things are a process that takes place over a long period of time.

Shipley: Like with Purple Snow, we went down so many different roads when we were making that record. We started out with a handful of tracks that we were interested in, and by the time we had done it, it was almost like we hadn’t even used fifteen or twenty things we originally wanted to use.

Sevier: There’s not even a point when you know that you have a compilation. Sometimes I think it starts with one track, really.

Shipley: That’s totally true. We’re working on a record right now that really started with one or two little songs and an idea, and asking how you build around that. We’ve actually gotten away from making compilations recently because they’re more difficult to make.

Why’s that?

Shipley: You have to license them.

Sevier: We’re still making them, though.

Shipley: These eighteen-artist things where you have to get all these different mastering rights and publishing rights.

Sevier: So we’ll do one major, multi-artist compilation a year where the artists aren’t really related in any way. That’s not totally abnormal; we’ll probably have one this year. It takes a lot of time to meet and get to know the artists and answer all the questions and allay all the fears. Sometimes licensing one song from one person can be as hard as licensing a full LP boxed set.

Where do the records come from? Are you out there digging?

Shipley: Digging is kinda over. There aren’t a lot of records just sitting out in record stores that are waiting to be snatched up and turned into reissues. At this point, it’s like eBay and people’s houses.

Sevier: I buy twenty or thirty records off of eBay a week, probably.

Shipley: But really a big part of what we’re doing is discovering. We’re acquiring studios, we’re getting into people’s houses and their unreleased recordings. And as a result of that, we’re finding music that was never made.

Why is it important that you tell your artists’ stories?

Sevier: That’s the context, without which there’s just some music you’ve never heard of.

Shipley: It’s really easy to put twenty songs on a compact disc or a double LP. Anybody can do that. It’s being able to know that there’s a greater purpose to it—from an academic perspective—that people may not get now. Some people buy our records, crack ’em open, listen to them once and put them back on the shelf. But our feeling is that in thirty or forty years, the library we’ve created will actually be a really important document of lost and forgotten American music. That might be a bit arrogant, but I truly believe that there are things we’re making right now that, if we weren’t making them, nobody would be making them. If you’re going to make it, do it right. FL

A Few Numero Highlights from Ken Shipley

A Few Numero Highlights from Ken Shipley

001

001

Eccentric Soul: The Capsoul Label

Begin at the beginning. The best independent soul label that ever existed. Period.

040

040

Good God!: Apocryphal Hymns

Damaged, outsider gospel music.

052

052

Ned Doheny, Separate Oceans

Coke-dusted LA marina rock with a side of blue-eyed peas.

202.4

202.4

Unwound, No Energy

Northwest post-punk for the white belt generation.

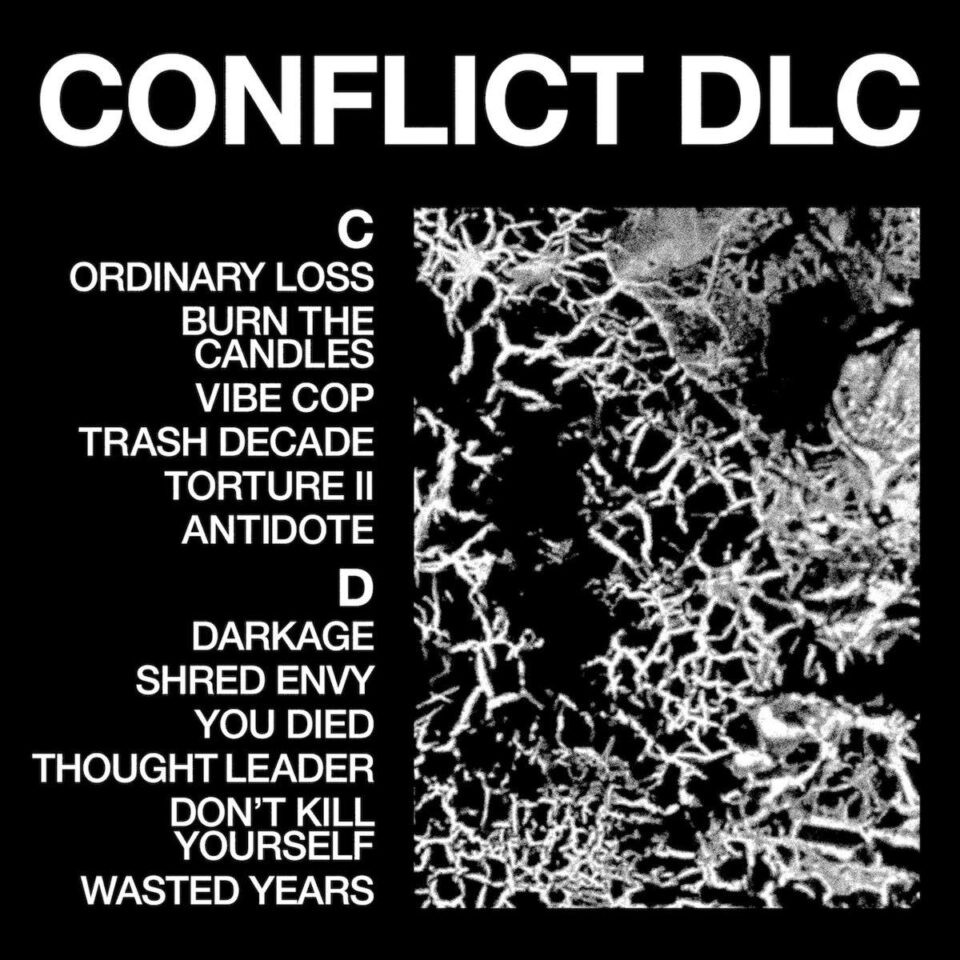

1208

1208

Syl Johnson, Is It Because I’m Black

Broken-hearted tales of a post-King/Kennedy America. The first soul concept album.