So what wasn’t working anymore?

At this juncture, in 2014, this particular topic of conversation is well past its expiration date, but Sebastien Grainger and Jesse F. Keeler are in good spirits, so they indulge. Again.

“It was…essentially—” Sebastien begins.

“…God, everything,” Jesse moans, his tone jokingly petulant.

Sebastien laughs. “Cumulative exhaustion. I don’t know. We’re making a movie about it, so you can watch that.”

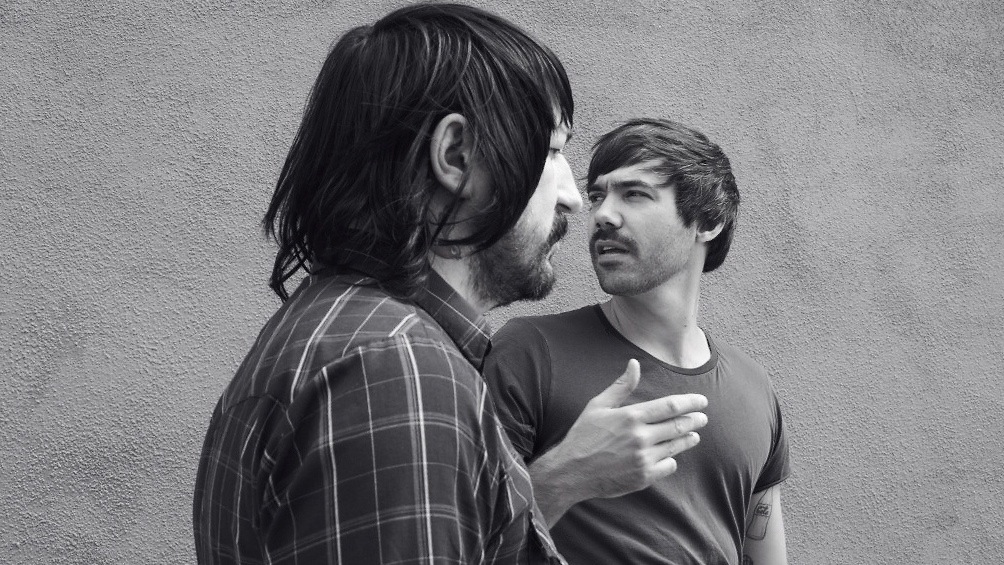

Today, in Los Angeles, the duo appear remarkably unchanged from their iconic logo—the black-and-white, dead-eyed portraitures with elephant proboscises emanating outwards—as if the past ten years haven’t happened at all. Sitting across the table from Grainger and Keeler now—laughing, wisecracking, finishing each other’s sentences, and giving genuinely thoughtful commentary to their infamous past—it’s difficult to put the tumultuous history of Death From Above 1979 into tangible context.

Again.

Death in youth. / courtesy Last Gang Records

In October 2004, the band put out their first and famously only full-length record, the dramatic and incendiary You’re a Woman, I’m a Machine. With only one EP preceding it (2002’s wryly titled Heads Up), the Toronto roommates made a lasting mark in the year that included the debut albums of Arcade Fire, Franz Ferdinand, Grizzly Bear, The Killers, and TV on the Radio. The masses struggled to define it—punk? Disco-punk? Disco-metal-punk? (“Or, whatever. Metal-hardcore-disco,” Grainger offers now, sardonically.) It was easiest to ditch all the labels and simply admit that it ruled. The deafening takes of danceable punk sermonized youthful sensuality and crisis, powered by a thumping, melodic bass wielded by Keeler and the frenzied drumming and frantic proclamations rhapsodized by Grainger. Eighteen short months later, in 2006, Death From Above 1979 was over, the duo had split—acrimoniously, rumor and speculation reported. (“When there’s this public relationship, maybe as it evolves or changes, people don’t like it and it becomes uncomfortable,” Keeler muses. “If the president got divorced right now it would be pretty upsetting, but totally no one’s fucking business.”)

“We went from being a prized stallion to being the horse at the glue factory. Just going around in a circle. And that is a bit soul-destroying,” says Keeler.

However, according to the band, it was terrifically more unceremonious than that. “I’ll summarize it this way,” Keeler offers, “When Sebastien said that he didn’t want to do the band anymore—which, to me, makes sense because, between the two of us, I’m the one that avoids difficult situations and Sebastien’s the one that says, ‘God, well, I’d better talk about it!’—we talked about it a bit. And I said, ‘OK.’”

“It was a relief,” Grainger confesses. “It was a hard decision to make, but it was a relief. Because it wasn’t working anymore. And our relationship… The good parts are the creative parts and there hadn’t been a creative moment in the band for two years. So, it was nothing—it was all repetition, repetition.”

“We went from being a prized stallion to being the horse at the glue factory. Just going around in a circle. And that is a bit soul-destroying,” says Keeler. “We had tried all kinds of things to help steer the band in a way that we wanted it to go and have things work in the way that we had imagined they would work, but in the end, the only way we were going to get out of the situations we were in was to stop. The disbelief from the people that we worked with was telling.”

It was done. For the next half-decade, each took up side projects—“They weren’t side projects, though!” Grainger interjects, laughing—Keeler joining friend and DFA1979 producer Al-P for the electronic project MSTRKRFT, while Grainer released a handful of records under his own name. But moving on was one thing in theory and another in practice.

“That was a difficult thing for both of us. I had to say, ‘Hey, don’t put Death From Above on the MSTRKRFT flyer. It’s misleading.’ Mainly ’cause I was like, ‘I don’t want to disappoint Death From Above fans; this is a different thing,’” Keeler explains. “It was a process just to get people to accept that this was something else.”

Grainger and Keeler may have been working seriously to move on from Death From Above, but the public was not so ready to accept the band was gone. There was the fight against the old status quo, but Keeler and Grainger also describe the struggle with fans. Both recount separate moments of physical conflict—one fan confronting Keeler in a bar and another shouting DFA1979 songs at Grainger while he was performing. Both incidents, surely not isolated occurrences, ended in blows. Both are also quick to point out that despite the ridiculousness of the situation, they also understand the passion on some level.

“Our band really, really existed and grew in our absence. It lived in our absence. And when we saw the evidence of that, and were confronted with it over and over again… That’s different than any other band or any other music that I’ve ever done,” says Keeler.

“I met John Reis once, when Drive Like Jehu was long gone,” Keeler remembers. “I went up to him and was like, ‘Man, Drive Like Jehu is such a big influence, it’s so important to me.’ Now I know, in his head, he was probably thinking, ‘I’m trying to move on with my life. I do other things.’”

“I did the same thing to the fucking bass player in Foo Fighters!” Grainger laughs. “I was like, ‘Ohmygod, Sunny Day Real Estate was my favorite band when I was seventeen.’ And he was like, ‘Cool. That’s great. I gotta go play with Foo Fighters; we’re the biggest band in the world.’”

However, the pyre the band had left behind continued to burn and spread. The record kept selling. Then it was repressed. T-shirts remained worn. Their logo was deified. Their name lived on in the deep, dark recesses of the Internet throughout the first decade of the new millennium; along with The Smiths and Neutral Milk Hotel, Death From Above 1979 was a frequent request for the crucial reunion slot at Coachella, usually laughed off and filed under: “dubious, at best.” Fellow Torontonians Crystal Castles notably sampled “Dead Womb” on their 2008 debut. The opening credits of MTV’s 2007 Aziz Ansari–Rob Huebel–Paul Scheer sketch comedy show Human Giant were soundtracked to “Romantic Rights.” Brazilian collective CSS’s still-best-known single is titled “Let’s Make Love and Listen To Death From Above.” While Grainger and Keeler had left the scene, someone had forgotten to extinguish the blaze.

“Our band really, really existed and grew in our absence. It lived in our absence. And when we saw the evidence of that, and were confronted with it over and over again… That’s different than any other band or any other music that I’ve ever done,” says Keeler. “In that time, kids were getting the fucking logo tattooed on their bodies. It’s like, ‘Fuck, people are still playing these records on college radio? They’re still buying our shirts?!’ We’re a band that’s long since broken up. We’re offering nothing at this point.”

By the end of 2010, it had been six years since You’re a Woman, I’m a Machine had been released, and Grainger and Keeler, barely communicating in the lead-up to the break-up, hadn’t spoken since the dissolution. When the catalyst for the reunion is brought up now, both break from the candor of the conversation thus far—“We should really start making up something more awesome than the truth. We’ve been so honest. We used to be such good liars,” Keeler laments—and invoke a previously relied upon DFA1979 interview tactic: fucking with the interviewer. In brief, Grainger had a down payment on a helicopter, and Keeler, working at the Bank of Canada, was able to secure the financed structured cash settlement he needed.

“I am now the proud owner of a helicopter,” Grainger beams.

Death lives. DFA1979 in 2011. / courtesy Last Gang Records

“Sebastien and I started to play together again before we told anyone, outside of our very, very immediate circle. We, in fact, told people to keep it secret. But we still didn’t know: We didn’t know what would happen when we were playing together; we didn’t know if, after years of talk—you don’t know that people will actually want to see your band in the end. My good friend Xavier [de Rosnay, of Justice] was like, ‘Just don’t make another record, just make that one, it’s so perfect,’ Keeler explains, adopting de Rosnay’s Parisian accent. “‘Just have the one record and never do anything else, it’s so good.’”

“We just wanted to see if people still liked the band, basically,” says Grainger.

“The thing was, that for so many years, everyone had told us that our band was so awesome. It was so important to them and they loved it so much. And that’s all well and good, but talk is, uh, often quite cheap,” explains Keeler, fervently. “We live in a time where to say you ‘like something’ really doesn’t involve any kind of sacrifice or effort. It’s just clicking a fucking thumbs up. After a while, you forget that being a fan of something requires—”

“…Participation,” finishes Grainger.

If the band had any doubts, they were swiftly laid to rest. In 2011, a surprise reunion at a SXSW show in Austin resulted in an over-capacity venue, chain-link fences torn down by the crowds outside, and the riot cops called. In April, against all past odds, the duo played the Coachella mainstage on the festival’s closing night. Keeler describes those shows, and specifically a set in May in London that year, as “headlining in this club that we would never have been pitched for [ten years ago], for two nights in a row, it sold out instantly, and everybody in the whole audience is singing the songs at the top of their lungs so loud that I can’t hear Sebastien singing while I’m playing the bass.”

Still, at resurrection, new material wasn’t guaranteed. The band rehearsed before playing their highly anticipated reunions shows, of course, but Keeler insists it was important for them not to just play old material. “[We needed to] be a band again and not just be a mummified body of our old band,” he explains. Grainger listened to demos Keeler had sketched out, writing down ideas of his own, and before long the band decided to put themselves in a room again and just play.

“Leave the comfortable area behind and just go forward and think forward,” Keeler says.

“What’s the challenge?” Grainger asks. “It’s writing new stuff, you know?”

Now in 2014, live at a show in August at the Troubadour in Los Angeles, the duo electrify and deafen as much, if not more, than they ever did. They were last here in 2002, opening for the Blood Brothers. Their van broke down and they slept on the side of the 5 freeway, almost calling it quits then and there. Now, Grainger asks for Carl Sagan’s help from the stage. The show that evening sold out, as he puts it, “in the space where time doesn’t exist. No-time.” The crowd swells and surges. The new songs are well received, and take their own, fitting place amongst the decade-old favorites. The encore of “Romantic Rights” begins, just as it always has, like a stubborn clunker whose engine won’t turn over, Keeler’s bass stuttering and thumping in disjointed rhythm, as Grainger’s unfaltering drumming gives it the gas it needs.

It may have taken three years a decade, but Death From Above 1979 have finally produced a follow-up to their 2004 debut and, as if testing its own veracity, it’s called The Physical World. It defies all the pre-conceived notions of a band in their position; this ain’t no desperate cash grab or half-hearted attempt to sustain relevancy. It’s not what Grainer and Keeler, nor Death From Above 1979, have ever remotely been about—nor would they ever be accused of trying to impress anyone. Yet, the new record—a bold and defiant pleasure—succeeds at doing just that. It was worth the wait. But how does it stand for the band?

“By my standards, it’s a fucking self-indulgently long record,” says Keeler. “I don’t think any record should be more than twenty-two minutes long. It’s better for the vinyl if the gaps are larger. They go deeper, and they’ll last longer. That’s just my opinion,” Keeler adds. “Because if you have more to do, if you have more to say: make another fucking record.” FL