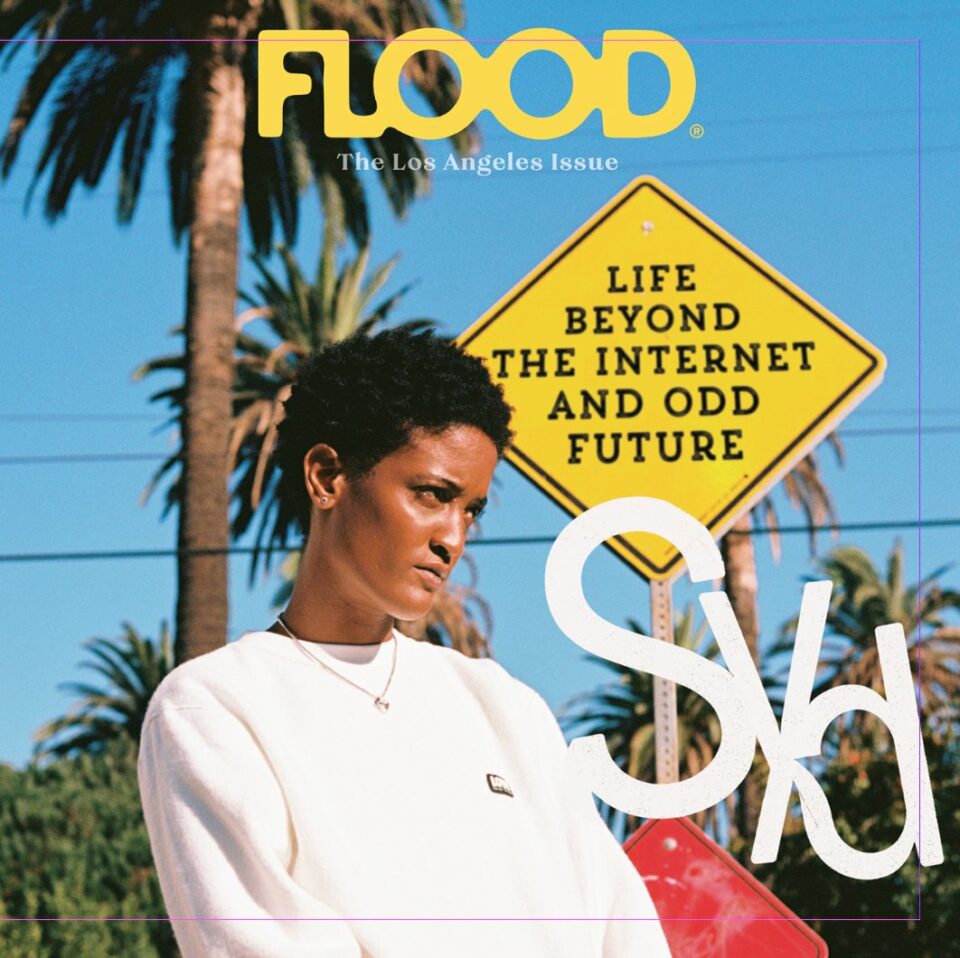

This article appears in FLOOD 12: The Los Angeles Issue. You can purchase this special 232-page print edition celebrating the people, places, music and art of LA here.

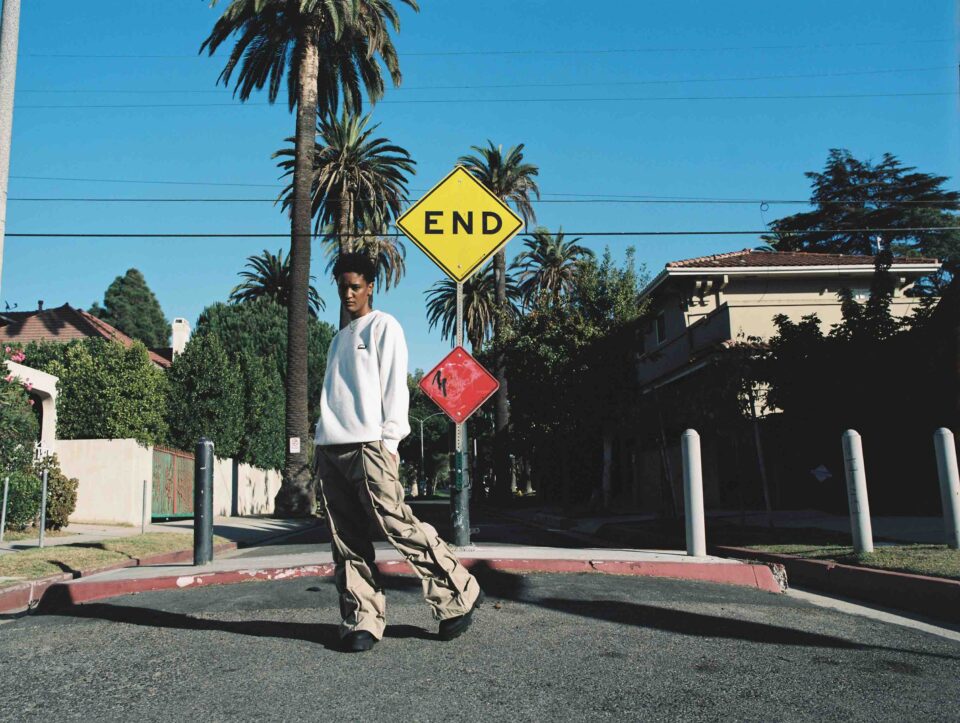

Syd is a creature of habit. Most mornings, she wakes up at her apartment in the Mid City neighborhood of Los Angeles. She goes to one of the three or four coffee places she cycles between, comes home, walks her dog. Sometimes she swings by her parents’ house nearby, where she grew up and lived until this past March. If her dad’s there, they might hit the In-N-Out location they’ve been going to together since she was a kid. She always orders the same thing. Then she spends the rest of the day working. Sometimes that means writing songs. Sometimes it means teaching herself video-editing software. If she doesn’t have anything else to do she’ll get on Skillshare and browse for things to learn about that she may or may not ever use in her work. Lately she’s been into typography.

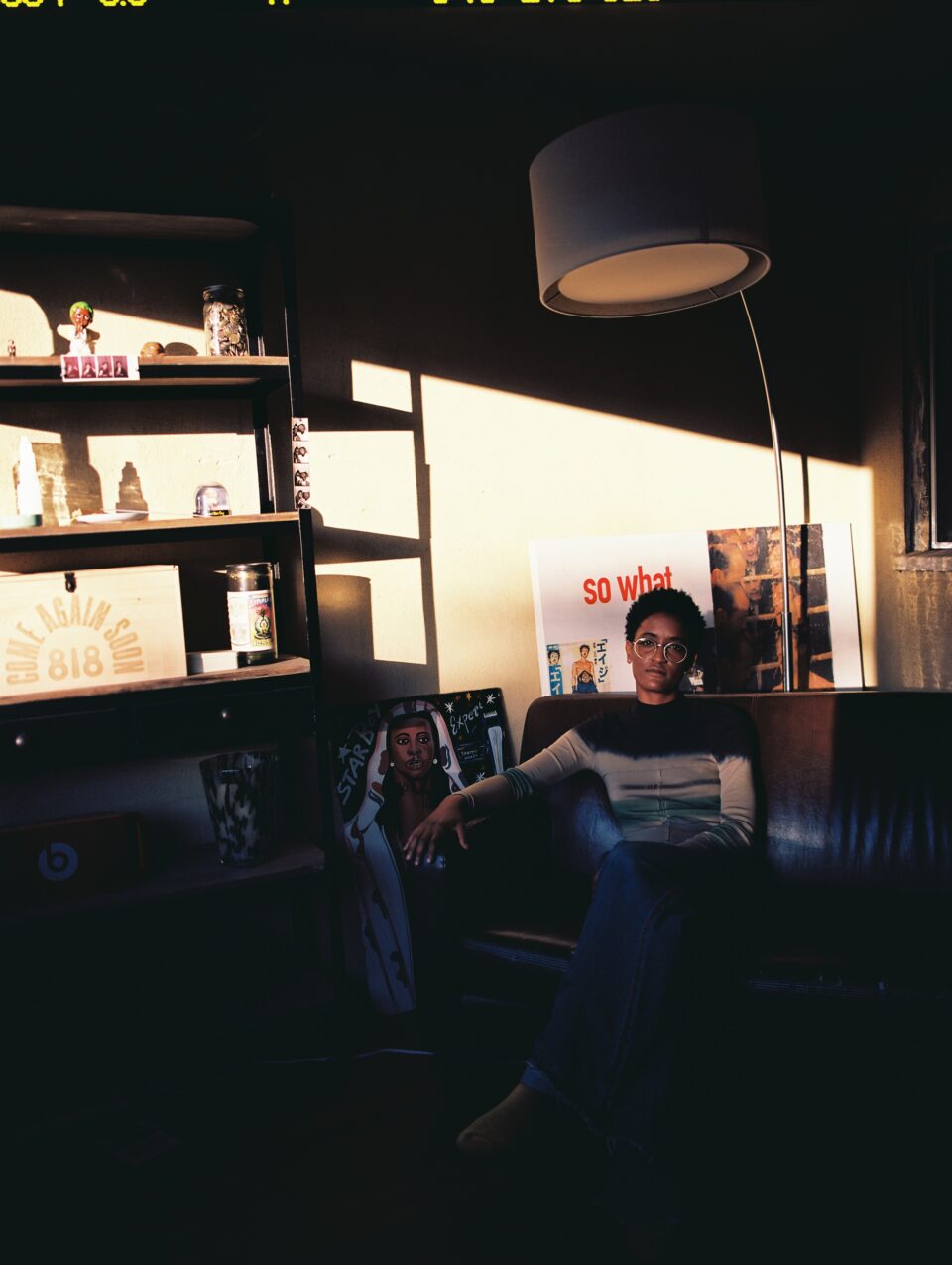

Syd’s daily schedule doesn’t fit most peoples’ idea of what pop stars are like. Not much about her does. In an era where celebrities assert their economic superiority with unprecedented aggression, she’s conspicuously unflossy and seemingly immune to most of the material trappings of artistic success. She’s usually in a uniform of jeans, T-shirt, and trucker hat, unless it’s a photoshoot or a special occasion. She runs her own social media accounts and answers her own DMs. Her Instagram, full of candid snapshots and screencaps of texts about houseplants, could be any average late-twenty-something’s, if you ignore the occasional magazine cover or Big Sean cameo. And while it’s become accepted for musicians to be brutally honest about only being in it for the money, and make music that sounds like they’d rather be doing almost anything other than making music, Syd remains a devoted workaholic and a diehard studio rat. She also happens to be a Black butch lesbian in an industry whose biggest commodity remains idealized white cishet femininity.

The fact that there’s room in pop these days for someone like Syd is largely because she’s made it herself. It’s hard to overstate the era-defining impact that the projects born in the studio in her parents’ guest house have had on modern pop culture, not just musically but in shaping the way people experience it. Her involvement in launching the rap collective Odd Future to viral stardom a decade ago would have been significant if the group had only produced as many great rappers, singers, and producers as it did, or if they had only snatched hip-hop away from credibility-obsessed gatekeepers and opened it up to kids who were creating their identities in the cultural swirl of social media platforms instead of the streets. But they also put a mix of joyful nihilism and naked vulnerability out into the world that’s been picked up by a huge swath of young Millennials and Zoomers who’ve grown up in their wake, while their Tumblr-to-Top-40 career arc helped change the entire music business’s attitude towards online culture.

Then, when Odd Future began splintering off into solo projects, Syd co-founded The Internet with OF producer Matt Martians, which, on top of a template for gently psychedelic neo-soul that’s been copied by countless R&B and indie-pop artists since, made live instrumentation cool again in a laptop-producer world, and created space for a new generation of sensitive, acid-dropping youths to come into their own. And you can’t count the number of queer kids—and adults—she’s influenced and inspired simply by being herself on such a big stage.

Not that Syd would ever cop to having changed the world. “I don't see it that much,” she demurs. “I also kind of tend to have my head up my own ass most of the time. I'm really selfish and in my own bubble most of the time. Honestly, I’m self-centered.”

She’s not. While it’s true that you have to be at least a little narcissistic to make it in the music business, precocious success, GRAMMY nominations, and a cultishly devoted fan base that includes more than a few superstar celebrities don’t seem to have overinflated Syd’s ego. On a Zoom call from her apartment, wearing the same Thailand souvenir shirt she’s wearing in half the pics on her IG, she’s warm and disarmingly funny, quick to laugh, fun to talk to, genuinely curious about the stranger on the other end of the line. She’s charming and just a little cocky. Anyone who interacts with her is bound to walk away with at least a small crush.

“It’s really hard to do everything yourself, man. I’ve tried it, I’m still trying, and I don’t like it. It’s lonely and it’s hard. I enjoy collaborating very much. I like being able to say that I was a part of that great thing with these other great people.”

Syd has a reputation for being aloof and inscrutable, at least if you believe her press. It’s easy to understand why people might get that impression. While her Odd Future cohorts were jumping over themselves to find ways to infuriate grown-ups, Syd was content to chill behind her turntables and coolly observe the chaos. In press photos she tends to affect a deadpan expression, frequently skirting the line of mean-mugging, that brings out the masculine side of her androgynous good looks.

In fact, she’s a quintessential team player, a trait she credits to all the time she spent playing basketball before music took over her life. She’s a generous collaborator, and quick to give credit to the people around her. She tends to learn best in group situations. “I’ll watch somebody do it once or twice, then if you give it to me, I'll just copy what they did. That's kind of how I learned how to play piano, and how I learned to do everything. Somebody did it in front of me, or I got on YouTube to watch somebody do it. Like, ‘OK, cool.’ And then I went home and downloaded the software.”

LA is a good place to get a musical education, especially if you’re the type who learns from watching. Growing up in the music industry capital gave Syd a lot of opportunities to see up close artists whose influence was rippling out from closely knit communities into the wider musical world. “There were so many different pockets of the LA music scene that you could find yourself a part of, infiltrate, and learn from,” she says. Her high school, the Hamilton Academy of Music, was ground zero for the hyperactive hip-hop varietal called jerk music, one of the first microgenres to blow up through social media rather than radio and MTV, launching viral dances a decade before TikTok. At the same time, she was also hanging out at The Baked Potato Jazz Club in Studio City with Vince Staples and Odd Future’s Left Brain, watching artists like Thundercat and fellow Hamilton alum Kamasi Washington lay the foundation for a surprisingly robust 21st century jazz revival that continues to unfold.

While Syd was still in high school, she started hanging around the houses of musicians like the production collective Sa-Ra, who worked with Talib Kweli, Erykah Badu, and John Legend while crafting their own space-funk originals on the side. “At the time,” she recalls, “they had a house in Silver Lake and they used to invite all the up-and-coming artists and producers over there just to, like, hang out, kick it, and make music and use all their toys.” The first time she ever mixed a track in Pro Tools was helping out Sa-Ra’s Om’Mas Keith on a solo record by Patrick Stump from Fall Out Boy.

Syd began paying her education-by-osmosis forward from the start, boosting up new talent even as she was still developing herself. Odd Future happened the way it did because of the jammy marathon recording sessions she hosted at her parents’ house, where “like eight dudes [would] sleep over every weekend and make music,” as she describes it, a training ground where her collaborators were able to refine their skills. The Internet incubated solo careers for all its members, including Steve Lacy, who’s gone on to become one of the most popular and influential guitarists of his generation.

“There are plenty of people out here who are doing it themselves,” Syd says, “or who look like they're doing it themselves, but they're not. It’s really hard to do everything yourself, man. I’ve tried it, I’m still trying, and I don’t like it. It’s lonely and it’s hard. I enjoy collaborating very much. I like being able to say that I was a part of that great thing with these other great people.”

With her high-level work ethic and love of collaboration, it’s not hard to imagine Syd thriving behind the scenes as a producer, songwriter, or keyboardist, all of which she’s good enough at to do full-time, but over the course of her career she’s eased her way into the spotlight. As The Internet’s lead singer, she was the collective’s most visible member, honing a dewy, supple voice and a swaggy stud persona that juxtaposed in unexpected ways to turn R&B’s heavily gendered loverman/sex-kitten dichotomy inside out. In 2017 she stepped out on her own with her debut solo album Fin, where she showed off a clearer pop focus, muting the jazzy psychedelic influence she picked up at The Baked Potato and bringing her love for Brandy and Aaliyah to the front of the mix. After regrouping with The Internet for 2018’s Hive Mind, she’s back on her own with a new solo project called Broken Hearts Club.

Syd started writing Broken Hearts Club during the early days of the pandemic, when she was locked down with her girlfriend at the time. “It was a relationship that was really great while it lasted—like, the best relationship I'd ever had,” she recalls. “You know, like, a no-issues type of relationship.” The first batch of songs she wrote for the album capture the heat of a romance in full bloom. “Fast Car” is a hard-edged, purple-tinged funk-pop ode to car sex dripping with ’80s production references—icy synths, gated-reverb drums—that takes a taut, funky vibe and squeezes it until it explodes in a soaring, gleefully shreddy guitar solo. “Right Track,” which she wrote on her girlfriend’s floor, is giddy bubblegum-R&B bliss, a mesh of shifting syncopated rhythms topped with a vocal melody that floats out of the speaker like Mariah Carey at her most buoyant. “I’m not what you like, and you like that,” Syd teases the object of her affection in a husky half-whisper, capturing in just a few syllables the intimacy of early romance and the queer joy of getting someone to reach beyond their usual preferences for you.

“There were so many different pockets of the LA music scene that you could find yourself a part of, infiltrate, and learn from.”

The relationship didn’t make it through quarantine, though. A few months into lockdown, Syd and her ex abruptly split up. “It was the hardest breakup I'd ever been through,” Syd says. “I'd say it was my first real heartbreak.” Instead of throwing out the love songs, she just reconfigured the project into a breakup album, adding in sadder cuts like “Out Loud,” which uncannily evokes the seasick feeling of knowing that a relationship is over before either side is willing to admit it.

The pandemic gave Syd space to process her feelings in the fallout from her breakup. “It was great for it to happen at a time where I had time to deal with it,” she says. “I couldn't really escape. I was able to really sit down for six months and reassess, you know, ‘Am I OK on my own?’”

The same question also applied to her music. Going solo had made Syd reconsider her creative identity. At age 29, she’s already had a longer career in the spotlight than most recording artists ever get, with no sign of slowing down, but she needed a change of direction if she wanted to keep going without burning out. She’s a self-described control freak, and the way she had been working before seemed to only give her either too little control or too much.

“I’ve learned that I'm an artist,” Syd says. “It sounds funny, but I think I struggled with accepting that for a long time. I'm accepting now that maybe I'm an artist, and not just a songwriter, not just a producer. For a long time I considered not releasing music as me, and just writing for other artists because I felt like that might be easier. When you're an artist, you're expected to perform, and I struggle a lot with performance anxiety.”

The problem with working for other people, she explains, is that “sometimes you write a song for somebody, and they change something, or they sing it weird, and you're just like, ‘Dang, that's not what it was supposed to be.’ I learned that from a production standpoint, too. I remember the first time I gave a beat to a really big artist and they recorded something on it, and I was like, ‘Oh, no, I don't like the song.’ Maybe I don't want to be a producer. I might be better off as an artist because I care way too much.”

“I’ve learned that I'm an artist. It sounds funny, but I think I struggled with accepting that for a long time. I'm accepting now that maybe I'm an artist, and not just a songwriter, not just a producer.”

For Syd, being an artist means taking her hands off the wheel, production-wise, and letting other beatmakers take over—at least for the most part. She was still putting the final touches on Broken Hearts Club when we talked, but she says she produced “three or four tracks” on the album. In typical Syd fashion—both control-freaky and communal—she picked her own collaborators, a mix of friends like Steve Lacy and R&B heavy-hitters like Trey Songz collaborator Troy Taylor. Features, including Kehlani and Smino, were arranged by DM instead of an A&R. (She reached out to singer Lucky Daye for a verse after her mom put her onto his music.)

Turning over the production responsibilities to others let Syd concentrate on writing and singing. Her voice is one of the only aspects of her talents where she expresses any self-doubt. “Singing is actually the one thing that I never feel good enough [about],” she says. She thinks she started taking it seriously too late—by which she means her late teens—and struggled with the training some of her coaches supplied. But her voice has grown into one of her greatest assets. Before, you could hear how unsure she felt being out front as a singer. Now, after taking over vocal training duties herself, it’s become strong but supple, airy but solid. It’s the kind of voice you wouldn’t mind hearing everywhere you go, in the club, in Lyfts, at the gym. Broken Hearts Club could be the album that turns her into that kind of pop presence.

At this point, Syd’s grateful for the stress that quarantine put her through, which has given her a new dedication to her craft—and a new gratitude for her breakup, which has opened up new paths for her, creatively and personally. “It needed to happen,” she says. “As hard as it was, and as much as I was hurt by it, and as much as I didn't want it to happen. I look back and I'm like, ‘Wow, nice. That was good.’” By the time she finished composing the album, she’d started writing songs about the process of rediscovering yourself after heartbreak, and had started dating model Ariana Simone.

She’s also become more comfortable in her own contradictions: The shy girl on the big stage. The semi-introverted recording geek aiming for pop stardom. The queer singer looking out at crowds full of straight girls. “It’s all confusing,” she laughs. “Me looking this way, and then at the same time being the little spoon, not wearing the pants in my relationship and sounding like Aaliyah on the track. But Aaliyah, you know, dressed in tomboy wear all the time. So, like, what's so different?”

What hasn’t changed, besides her daily routine, is her unfailing belief that music should be a communal experience, something much bigger than the person making it. Breakup albums are by nature a solipsistic, self-indulgent form, vessels for mopey navel-gazing and venting bruised egos. But Syd wants Broken Hearts Club to be something different, more than simply a document of her own hurt—something that can impart some of the wisdom and self-confidence she’s earned through her experience, that can inspire listeners, or at least give them the comfort of knowing that they’re not alone. “I want to make it a real club one day, where all the lonelies gather,” she says, maybe just daydreaming, or maybe considering yet another project to occupy her endlessly creative mind. “If you've gone through a breakup, here's the club for you. Join now.” FL