It’s a cold, rainy October night in 1997—perhaps a redundant weather report for Vancouver. I get out of a cab in front of the Starfish Room. At the same time, from a white Econoline tour van parked in front of the club emerges a plaid-clad boilerman and we meet at the door, head up the treacherous damp staircase together. I stare at him the whole walk, and I can tell he’s annoyed by my gaze. He stops. I stop. He turns to me and before he can tell me to fuck off I say, “I’m going to see you play,” and through a gruff baritone chewing broken glass Mike Watt replies, “Good for you.”

A quarter-century later I’m sitting with Watt at a picnic table on the grounds of Mass MoCA in a white-stone graveled parkette surrounded by giant pink cocks (Franz West’s Les Pommes d’Adam is supposedly inspired by “the Adam’s apple, pointing to the distinctive anatomical profile of a man’s throat,” but everyone agrees they’re dicks). Watt and I are in the same place at the same time for the second time, spending the weekend in North Adams, Massachusetts at Wilco’s Solid Sound music festival. He doesn’t recall Vancouver the way I do, but he understands community in a way I envy, a way I’m still trying to find.

“Bass players are like glue—glue with nothing to stick to just a puddle,” he explains. “Also, the politics of bass: you look good by making other people look good. I'm very grateful to D. Boon’s mother; she put me on bass. I was 12 years old. I didn't know what it was. The first gig we went to was T Rex. And they were this big, right”—Watt shows a very small space between his index finger and thumb. “I didn't even know they had bigger strings. Music is so much more accessible now. So it’s kind of mysterious. But I'm so glad I ended up on it.

Watt is at Solid Sound because of his relationship with Nels Cline. Watt introduced the Wilco guitarist to his now-wife (Cibo Matto’s Yuka Honda), played on numerous Watt albums and in Watt bands, and was not at the Vancouver show even though that’s how I remember it. (Joe Baiza subbed for Cline.) A few hours after we talk, Cline will join him and the Missingmen (guitarist Tom Watson and drummer Raul Morales) for a 17-minute rendition of “We Are Time” where Watt refused to let Cline end his solo, challenging him with the bass to look better and better. Dude jams econo, man.

The absence of live shows has been a void during the pandemic... Music is as close, culturally, as we get to love—an inexplicable affection that transcends rationale or definition.

I’ve been telling the Watt story for 24 years. It’s quite likely apocryphal, but I’m 45 and sober, so every-fucking-thing before five years ago is apocrypha. And I tell it, because I like it—I like believing the memory.

I was 22 years old living in Vancouver, 2,666 miles from my family in Ottawa. I was an idiot, but I had a community: an ex-girlfriend, a current girlfriend, a guy who lived on my couch, and a congress of bartenders, line cooks, addicts, and dealers—a similarly lost collection of East Coasters relocated to find themselves in gray, suffused West Coast light. A few months later, the girlfriend left me for the guy on my couch. They’re still together. He's bald and I’ve got great hair, so I’m OK with it. And they’d both opened up my musical horizons. As an Ontario grunge boy, my tastes hadn’t expanded much beyond Neil Young, The Tragically Hip, and Nirvana; the balded and the newer ex left me Will Oldham, fIREHOSE, Geraldine Fibbers, Uncle Tupelo, and others who never got airplay on Ottawa FM radio.

That fistful of exes and people whose names I’ve forgotten gave me a community back then, one bound by escape and good music. I’m not sure I’ve had that since, a commonwealth of friends born not of geography, but a sense of outliership and songs whose refrains felt like we had written them, peers on similarly lost plains.

I’ve become obsessed with notions of community. As we begin our escape from COVID, and the world around us descends into the chaos of socioeconomic and political polarity, I’m desperately trying to put my communities back together. For nearly three years I mostly bubbled with three people, and now that we’re once again drawn to public spaces, I feel lost, alone, isolated.

Few communities build like those amassed through music. The absence of live shows has been a void during the pandemic, a time without like-minded strangers drawn together by refrains, subjectivity, and involuntary ardence. Music is as close, culturally, as we get to love—an inexplicable affection that transcends rationale or definition.

In the most challenging moment of my generation, as we collectively hold our breaths in fear of what may attempt to break us next, we need love, we need community, we need each other. We need music.

Community is an inescapable entity this weekend in the Berkshires. As the pandemic peels away from its governance, we find ourselves drawn together by Wilco. Solid Sound is not Bonnaroo, it’s not Coachella—and thank god for that. It feels like a Memorial Day with friends, infused with art and music and local food trucks and forests of lawn chairs and kids in band t-shirts.

I felt this while walking around Solid Sound, dancing with strangers, hearing songs for the first time, or songs I’ve heard more than I can count. In the most challenging moment of my generation, as we collectively hold our breaths in fear of what may attempt to break us next, we need love, we need community, we need each other. We need music.

A friend comes up for Saturday. He’s excited to see Japanese Breakfast—with whom I have no relationship—and no one else. He lends me Michelle Zauner’s memoir Crying in H Mart a few weeks before the show. It’s brilliant, and I’m reminded that writing—a community that tends to disrespect the ideal of the word—is still everything.

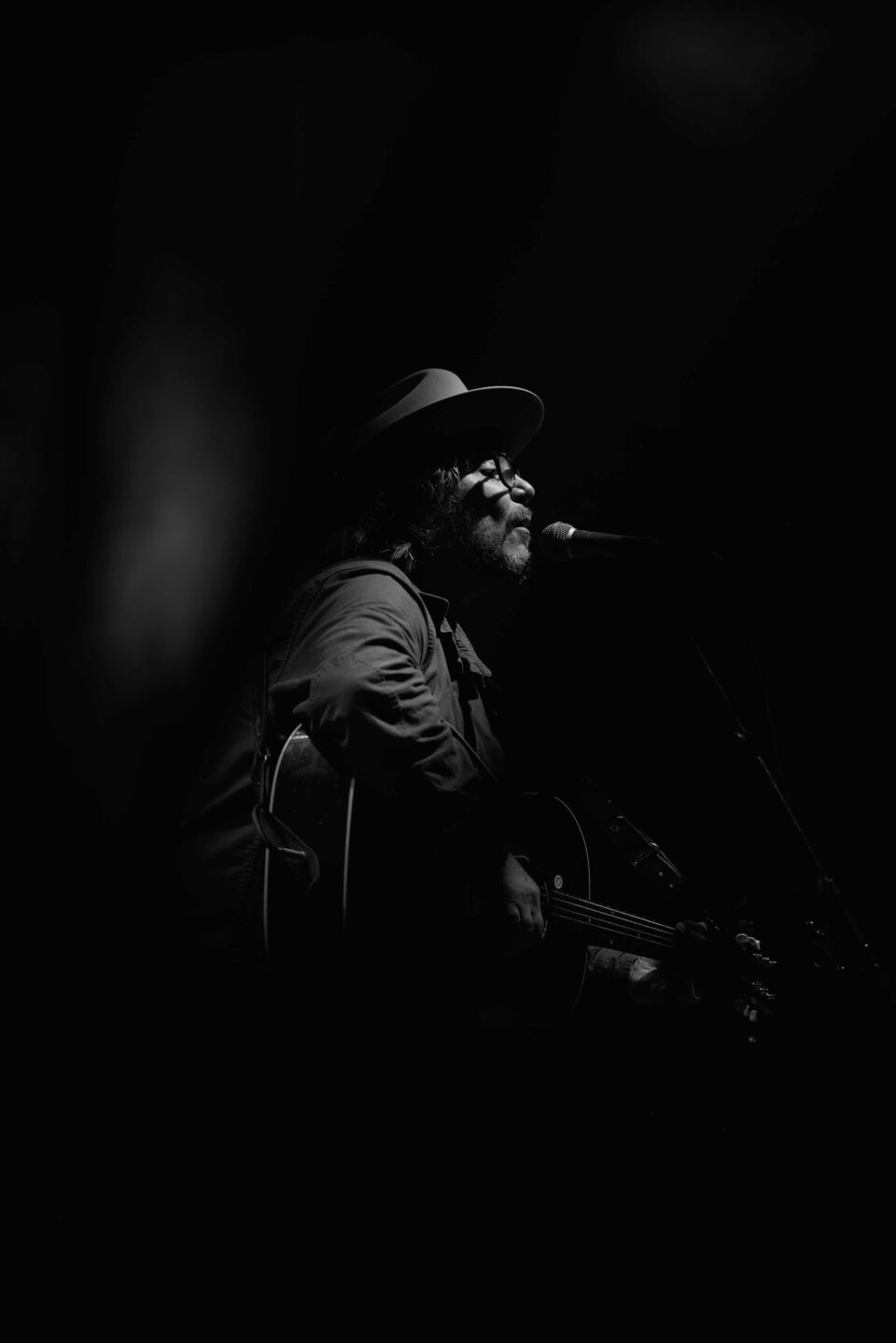

We catch Watt two hours before Breakfast, in a mudded field after a hard rain. The crowd is damp, but thick in reverence of a living, breathing connective tissue.

“The other thing is the movement itself,” Watt told me when we were discussing community. “People, yeah. I mean, later on people like Nels who could really play and stuff. But at first, it was just anybody who wanted to start a band. So go up to Hollywood, you meet all these strange people. And SoCal, it’s really vulcanized, nobody knows each other. But it’s a group—a couple hundred people every week—with funny names and funny clothes. And community. Yeah, there’s something about that. So I think when people are dealing with each other, probably the most ethical way is to take turns. Inhale, exhale, take direction, give direction. Make a new connection. If your mind is open, I think you sincerely believe everyone’s got something they can teach.”

It’s my third Solid Sound, and Mass MoCA is one of my favorite places. I escaped an abusive relationship to the 2017 incarnation, soothed by the company of strangers, Big Thief, Kurt Vile, “Kidsmoke.” I have a souvenir of that relationship, besides PTSD—a cheese board she gifted me with our initials burned into it made by Nick Offerman’s Woodshop. Offerman’s here, this year, un-mustachioed and paneling John Hodgman's Comedy Cabaret and a Substack Mystery Hour with Neko Case and Jeff Tweedy. When I ask his publicist for a few minutes to ask him how to reclaim my rightful cheese board, she doesn’t reply—but I get it.

In 2019, I was here just before David Berman died (the last live music I saw before I was supposed to see Purple Mountains on the other side of the Berkshires, in Kingston, NY), before COVID, when the world still made a bit of sense.

I fell in love here once, about a year ago, in the soft rain of an empty Joe’s Field. She was supposed to be with me this weekend, and her absence is tangible. I feel its weight. In the ever-present rain, in friends dancing, in the prescient apparitions of young families, and older couples, in choruses both sung and imagined. She’s an acquaintance of Bonnie “Prince” Billy, and Drag City set up 15 minutes for us to chat. I’ll ask if he’s seen her. If she mentioned me. If her new boyfriend is her old boyfriend, or if that relationship only exists in the nightmares of my freshly broken heart.

With Japanese Breakfast, I’ve found something new—a sense of tomorrow within the cacophony of yesterdays. Songs to play on the drive home, not to look back in the comforting twang of wallow, but forward to something, anything, everything. Anew.

Ultimately, our schedules don’t align, and Bonnie and I don’t get an opportunity to talk about me. But he does play a singularly Will Oldham set, to a courtyard of a few hundred people who may not have found grace in his music the way I have. On this afternoon, he gathered vagabond musicians and new songs handed out on bright fluorescent green paper—perhaps to match his head-to-toe emerald luminescent outfit—to the audience. Oldham’s work has carried me at times, finding comfort in “West Palm Beach,” “Grand Dark Feeling of Emptiness,” and “Hard Life.” Few artists know the strength we find in sorrow like Oldham. Maybe I would’ve asked him about that.

My friend skipped Bonnie and texts me furiously from Joe’s Field and its ghosts of affliction: “Will make strategic sense to lose some BPB and get here for JB + Wilco.” His argot is singular and poetic, and convincing. I sneak away from Bonnie and make my way to the front of the main stage where he has a spot for us. I’m skeptical of Japanese Breakfast—I’ve only heard a few songs and make a joke: What do you call JB fans? Omelets.

The band arrives to a crowd of mostly Wilco fans staking out their front row dance spots. Zauner, the creative force behind the band, tells the audience Wilco is her favorite band. A cynic would dismiss her, but there’s an organic, genuine truth to her that is unmistakable. She walked down the aisle to a Wilco song. Within minutes the crowd is enamored, we’re hers, we’re theirs, buoyed by the JB fans whose enthusiasm is infectious and the band itself, whose performance is transcendent. Cline joins for “Posing for Cars,” and the band is filled with joy and reverence, which comes through the speakers and fills the crowd with the same.

I’m a convert. We are omelets.

In the fall of 2001, another era marred by fear and tumult, a woman I felt connected to—inexplicably, like music, and what could’ve been love—burned me a copy of Wilco’s Yankee Hotel Foxtrot. I was going to celebrate the album no matter what, a young man’s effort to impress her culturally, to find a bond beyond whatever we had in the confusion of infatuation. But that album lasted me longer than the infatuation, than the confusion, than the relationship. From “I Am Trying to Break Your Heart” onwards, I was in love.

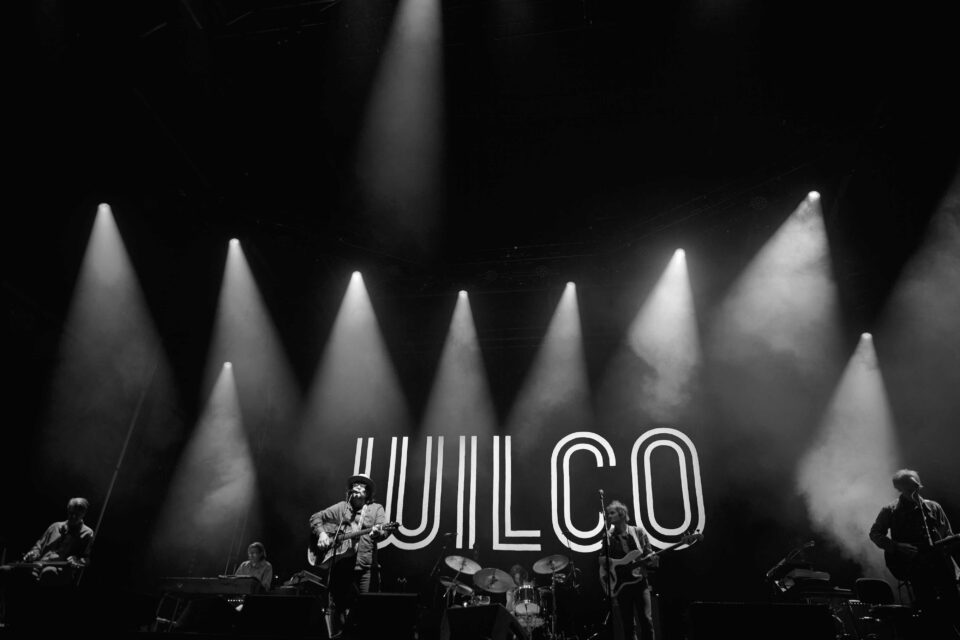

On the opening Friday night of Solid Sound, a Memorial Day weekend traced in a pandemic, Wilco plays their new album, Cruel Country, in its entirety. The double album confronts our cultural present while indulging in the band’s musical past. It’s an achievement, a magnum opus, a realization of a band that has scored the past 25 years with its catalog. All ticket holders were sent a free digital copy earlier that day, but a bold move nonetheless playing a full set of songs that most people in the crowd don’t know. It speaks to Wilco’s sense of community, their understanding of who joins them at Solid Sound. It’s their people, family in a broad sense—those who are brought together by a band that has endured in a time when our collective endurance is being forever tested.

Saturday, after Japanese Breakfast became everyone's new favorite band, Wilco took the stage for a set that rewarded their community’s patience, through rain and new songs, through a public-health and existential crisis. “War on War,” “Muzzle of Bees,” “Impossible Germany,” and “Jesus Etc.” (with Michelle Zauner) punctuated a set of both familiar and new music that reminded the crowd exactly why we endure, why we continue on; for intermission from chaos and threat, for the collective, for moments of community. Bringing Zauner onstage is not an act of pageantry, but rather recognition of their role in her life and hers in theirs. And in ours.

Sunday, Jeff Tweedy and friends put an end to the weekend with a stage of guests and songs that played the weekend to rest. During the encore, Jeff’s son Sammy joined him for a cover of Neil Young’s “Helpless,” a reminder that we would soon return to where we were lost. David Byrne joined for the finale, a rendition of “California Stars.” Then we’re all off, to elsewhere, to the road.

Solid Sound Festival at MASS MoCA

Music isn’t just art or entertainment. It’s a compass with which we map our lives through the work and experience of others, together and apart. It’s the soundtrack to our best days and worst nights, our love and heartbreak. It’s the vessel through which we indulge vicarity without judgment. It’s what brings us closer, and what plays in the background as we pull apart. From Watt to Bonnie to Cline to Wilco, I’ve made my way here, through loves lost and memories faded, haunted and yet eager to continue along the road, to fill in scenes around the soundtrack. And with Japanese Breakfast, I’ve found something new—a sense of tomorrow within the cacophony of yesterdays. Songs to play on the drive home, not to look back in the comforting twang of wallow, but forward to something, anything, everything. Anew.

Somewhere, in the shadows of North Adams’ once-great mills, Watt’s back in the Econoline. “I do maintenance. You’re talking 39 years. That's really 40 years of doing this. But touring, basically do it the same way. Clockwise in the fall, clockwise in the spring. It’s kind of tradition to vaudeville. I let you know, there was a time when you didn’t have recorded things, on cylinders or discs. And the guy working the farm or the factory, he had to wait for you to come to the town and form it for him. In the field.”

Part of me will be forever in that field, in wait, in wonder, for all that music has given me to come back, and dance with strangers to the rhythm of those who have left. FL

Solid Sound Festival at MASS MoCA