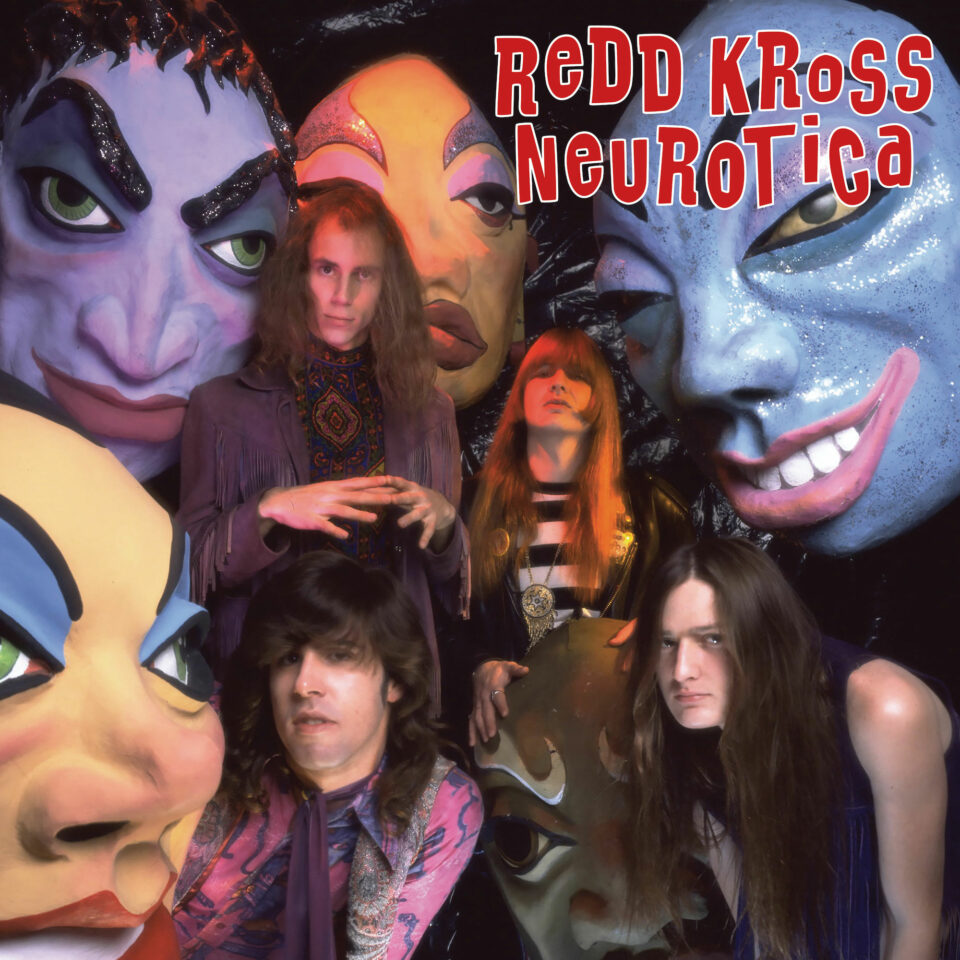

“Come on lose your mind / Now you’re one of us,” sang Jeff McDonald on the title track of Neurotica, the 1987 album that heralded the LA-based quartet Redd Kross’s full transition from KISS-obsessed weirdos with roots in the South Bay hardcore scene to one of the great American bands of the alternative rock era.

Released at a time when hair metal bands were offering irony-free sleaze and most alt-rock acts were grimly imitating either R.E.M. or The Stooges, Neurotica stood out with its giddy blast of bubblegum-flavored hooks, roaring punk guitars, bell-bottomed hard-rock riffage, and lyrics that celebrated ’60s and ’70s pop cultural references. The album wasn’t just a series of flashbacks, however; tracks like “Play My Song,” “Frosted Flake,” and “Peach Kelli Pop” also eviscerated the lame, cocaine-driven culture of LA’s Sunset Strip–centered music scene.

Though the album didn’t sell particularly well, for those who “got” what McDonald, his younger bass-playing brother Steven, drummer Roy McDonald (no relation), and lead guitarist Robert Hecker were laying down, Neurotica offered an alluring invitation to lose one’s mind, indeed. The album’s unique sound and aesthetic—imagine Cheap Trick doing a soundtrack for a John Waters film—would leave a deep impression on bands like Sonic Youth, Nirvana, Stone Temple Pilots, and Teenage Fanclub, to name just a few.

Previously reissued in 2002 and 2007, Neurotica returns on June 24 for its 35th anniversary, this time in an expanded edition via Merge that features both a 14-track version of the album (including finished outtakes “Pink Piece of Peace” and a cover of Sonny & Cher’s “It’s the Little Things,” neither of which were on the original 1987 release) and a dozen previously unreleased Neurotica demos from 1986. The demo tracks make for fascinating listening, both because they’re considerably rawer than the finished album—which was produced by Thomas Erdelyi, a.k.a. Tommy Ramone—and because they really allow you to hear the band’s musical evolution in progress.

We spoke with Steven McDonald about the making of the album, the influences that led to its creation, and why people still love the record so much to this day.

There was a three-year lag between 1984’s Teen Babes From Monsanto, which was essentially a collection of cover songs, and Neurotica. In that time, you guys really evolved, both as songwriters and as a musical unit. Do you remember how that happened?

Those demos were recorded in ’86, which I'm realizing is the year after I graduated from high school. And by then, we had been doing it for seven years. We weren’t very prolific songwriters—we still aren’t—but it wasn't like we were just kind of hanging out and flaking off all the time; we were down in the laboratory trying to get our show together. We were always really motivated to put on a great live show, and that's kind of what Neurotica came out of.

“As much as we’re making fun of the hair metal scene, we’re also kind of saying, ‘Don’t box me into a punk rock scene, either.’”

You guys had a cult following in LA, but what you were doing was very different from what else was happening there at the time. Several Neurotica songs quite clearly express disdain for the hair metal scene.

Sure—but as much as we're making fun of the hair metal scene, we're also kind of saying, “Don't box me into a punk rock scene, either.” We would play shows with some of those SST bands, but we felt like that was limiting, as well. We wanted to go beyond that.

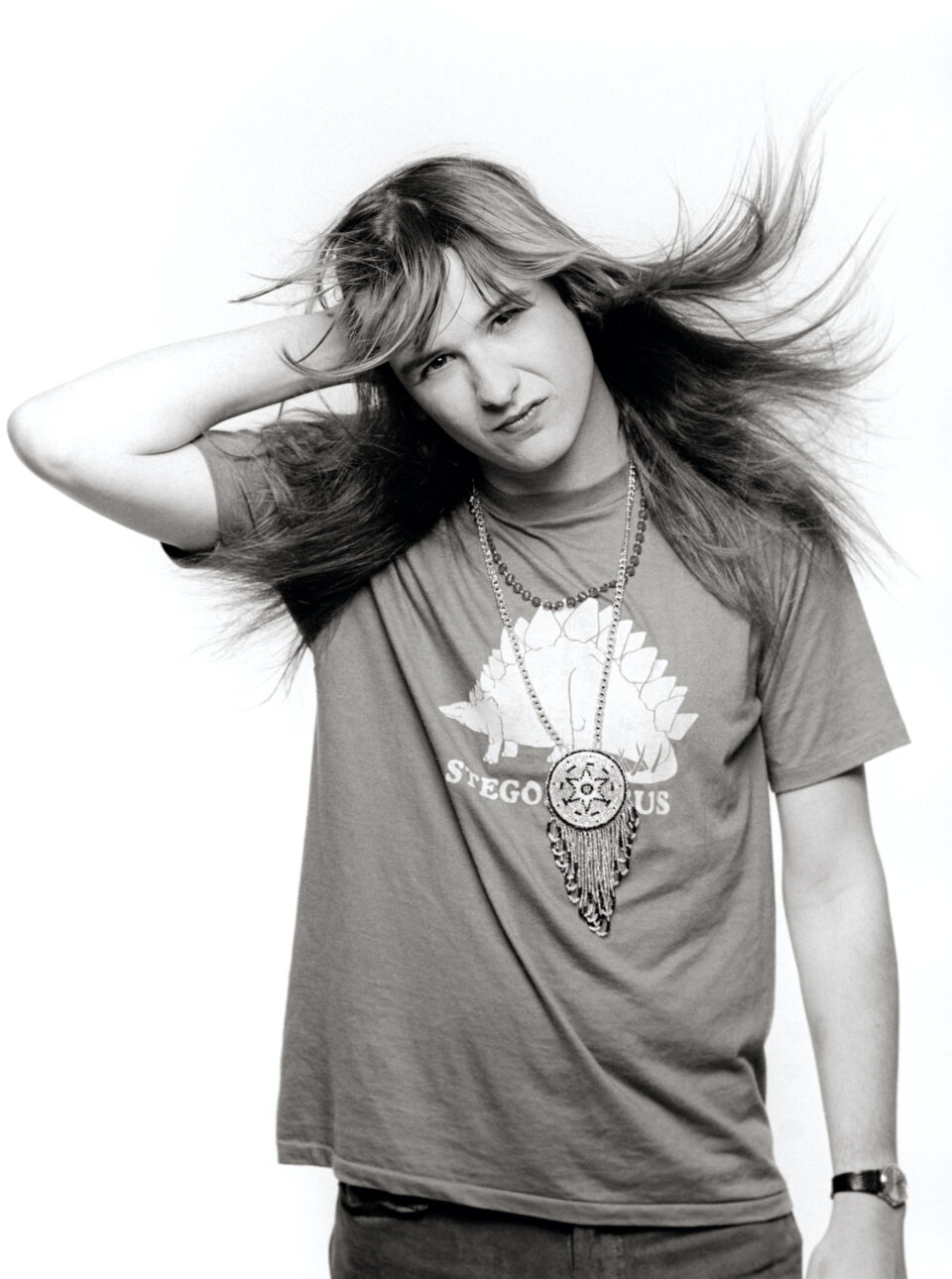

Steven McDonald

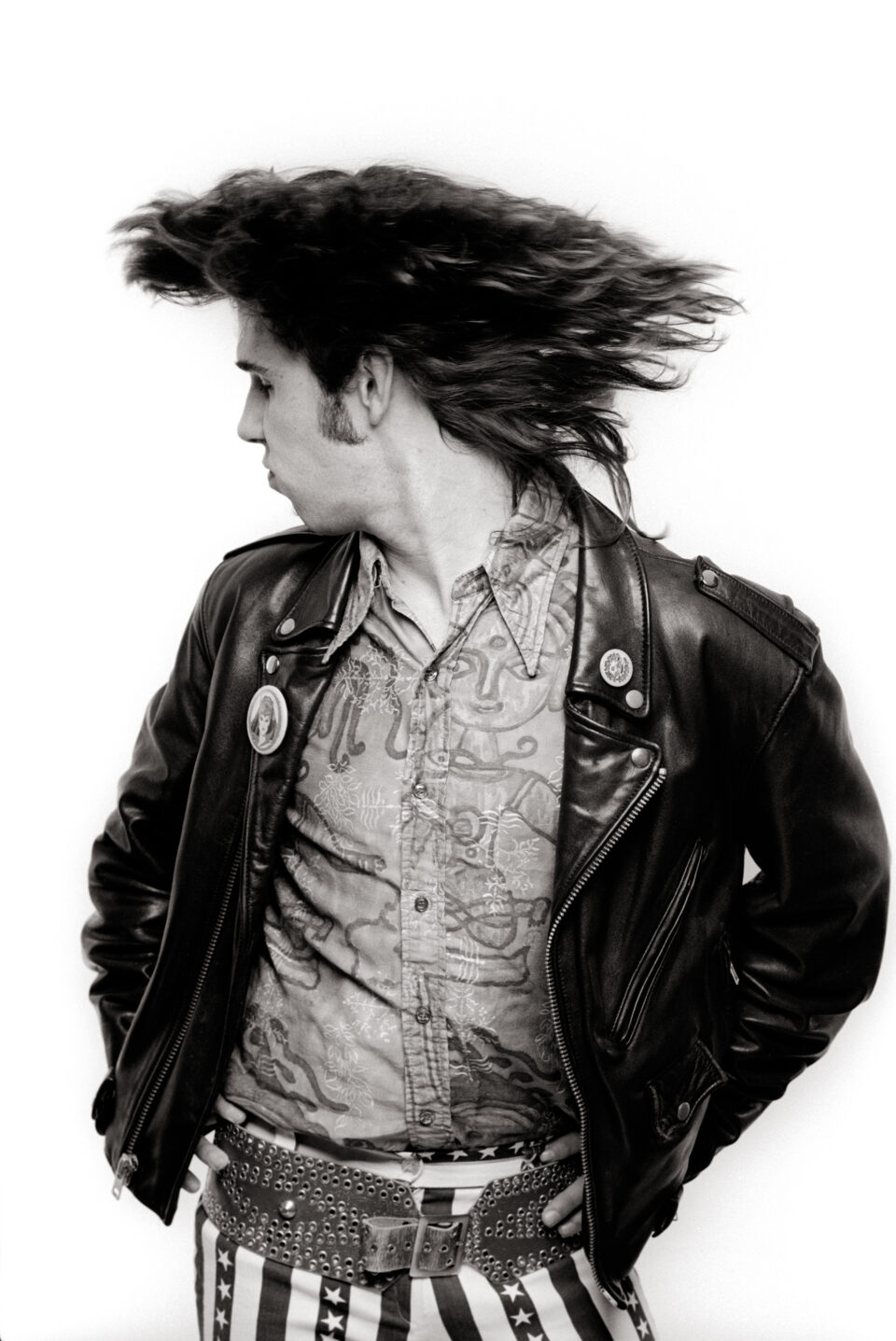

Jeffrey McDonald

Robert Hecker

Roy McDonald

Teen Babes made that pretty clear—you guys covered everything on it from KISS to David Bowie to Boyce & Hart.

Jeff was always exposing me to weird music, and he's only three years older than me. So, you know, how did that happen? I mean, there was never a time in my life where “I'm Eighteen” by Alice Cooper didn't exist. And then I remember in Christmas of 1972, our uncle Shane, who's like 12 years older than me, had an 8-track copy of Ziggy Stardust, and he wasn't really interested in it. Jeff was immediately attracted to it, and Shane said, “You guys can borrow that if you want.” We never gave it back, and within a few weeks, Jeff had gotten all the Bowie back catalog, so I was listening to Hunky Dory when I was, like, five years old!

Jeff always talks about how he went to the local shopping mall when he was 10 and bought Aladdin Sane, and the hippie girl behind the counter just looked at him with disgust, like he was buying a bestiality magazine or something. She said to him, “Do you know what this is?” Like she felt it was her responsibility to warn the kid of what a gross thing he was getting himself involved in [laughs].

“I think we were always trying to find that sweet spot between the Partridge Family and The Who Live at Leeds. I don’t know if we nailed any of it, but we definitely came up with our own thing in the process.”

Jeff was not one of those older siblings that didn't want their younger sibling around; he really liked introducing me to all this stuff. And he had that same mentality in 1983-84, when he started collecting songs that he wanted us to cover for Teen Babes—or, as he called it, “our Pin-Ups, a rock n’ roll history lesson.” He’s barely 20 himself at this point, but he’s already schooling everybody.

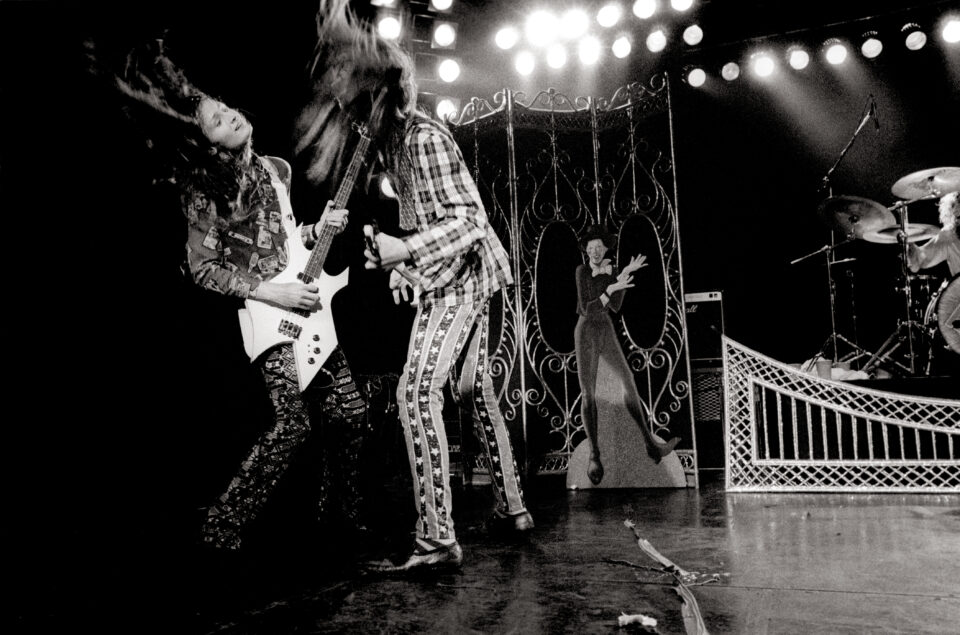

Steven McDonald and Jeffrey McDonald, Variety Arts Center, Downtown Los Angeles, California. 23 September 1988.

Neurotica had a similar thing, in the way that it drew upon and mixed up all these influences from the past, but it didn’t sound like throwback music. You weren’t copying a specific period sound, like the bands in LA’s ’80s garage scene.

I think we were always trying to find that sweet spot between the Partridge Family and The Who Live at Leeds. I don't know if we nailed any of it, but we definitely came up with our own thing in the process. It’s funny you bring up that Greg Shaw/Bomp Records/Cavern Club scene in Hollywood, which was a very small, insular world. In the later years of high school, I spent a lot of time going to the Cavern Club, because although I didn't want to limit myself to only dressing in mod clothing from, you know, November ’65—and those people were very specific about their references [laughs]—I didn't really relate to popular music of the '80s, either, and I preferred what was happening at the Cavern Club.

Steven McDonald

We kind of existed in this great charmed space, where we were granted access to environments that other people may have been excluded from. We could jam with Sky Saxon—which we did during that time, “with mixed results” as Jeff would say—but at the same time we were accepted in that Paisley Underground scene that The Bangles and The Three O’Clock and The Dream Syndicate came out of; those bands were our friends, and we had friends in the SST world as well. We even played a show with Poison once, before we ever saw them, and it was so mortifying to us that anybody would think that we had anything in common with these assholes. [laughs].

“We played a show with Poison once, before we ever saw them, and it was so mortifying to us that anybody would think that we had anything in common with these assholes.”

But my point is, we got to interact with all these different kinds of movements or scenes without ever feeling any kind of exterior pressure to somehow conform to what that scene was. At least amongst the music makers, the scene makers themselves, we were given a certain amount of respect. And, you know, I think Jeff stopped wanting to be a part of anything around 1981. I was definitely more of a standard teenager who would've been glad to conform to whatever was popular in 1981, but I remember the day he told me he was no longer cutting his hair, and he suggested that I stop, too. I was like, “Wow, I just got a cool punk haircut!” And he was like, “Yeah, well, I don't know; I'm not doing it anymore.” And that was him rejecting the whole Orange County punk scene.

How did Thomas Erdelyi get involved with producing the record?

Well, when we were still on Enigma Records, who put out Teen Babes, we had a loose idea that Kim Fowley would produce our next record, but Enigma wasn’t really offering us any money for it. Kim had told me that Enigma had given Poison $25,000 to make their record, and I was outraged. I was incensed! I walked into [Enigma co-founder] Bill Hein’s office, an indignant 16 year old, and I told him that he was making a grave error and that Poison would never do anything [laughs].

So, flash forward to '86 and we finally get our 25 grand or whatever—Big Time Records is gonna give us some money to get a producer. We really loved the most recent Ramones album that had come out, Too Tough to Die; it was definitely a return to form and they’d done it with Tommy producing. And then Tommy had just done that Replacements record, Tim, and he was kind of available at that moment—and we were this happening band in LA, and we had some money and enough things going for us to get him to come to Los Angeles and record us.

How was it working with him? Did he give you guys much guidance?

Yeah, I think he tried to help us refine our performances, maybe not rush the tempos, a lot of technical things. Some stuff, looking back now, I kind of wish that no one had ever tried to impart to us [laughs]—things that I feel kill some of the spontaneity in our recording—but I understand where he was coming from. At the time, the model of a band that was coming from the underground and then making it into that college radio world would've been R.E.M., so that might have been a secret point of reference for him, like, “Maybe we can sort of get some of those qualities onto this recording.” But that was nothing that we really cared about. We were mostly listening to '60s records [laughs]; Too Tough to Die was the most up-to-date thing I had given two shits about.

Redd Kross on set of “I.R.S.: The Cutting Edge” taping at Windows of Hollywood, Hollywood, California. 17 August 1987. L-R: Jeffrey McDonald, Roy McDonald, Robert Hecker, and Steven McDonald.

On the demo for “What They Say,” Robert Hecker sings it like he’s doing a Paul Stanley impression, but he takes a much different vocal approach on the actual record. Did Tommy tell him to stop singing it like Paul Stanley?

That would've been Tommy, not us. We would've been encouraging it 100 percent [laughs]. Another thing about Tommy I remember, we told him, “Yeah, we like the bass sound in ‘Good Times, Bad Times’ by Led Zeppelin.” And he was just looking at us like, “What are you talking about?” Like, “That's so yesterday, we gotta move on!” He’s thinking about competing with his peers who are having success with bands like R.E.M. or whatever, you know? And we're like, “We don't give a fuck about that—we’re into Led Zeppelin!” I later would have that similar experience when I produced The Donnas; they would play me early Motley Crüe records and I would just be like, “Are you kidding?” [laughs].

35 years on, what does Neurotica mean to you—and why does it keep finding new fans?

For me, it's just another record. But in terms of why I think it might keep coming back, I think it's the moment that it intersected with. It’s where my brother and I were in our development—we were these weirdos who were a little ahead of the curve with our graduating class—and then it just happened to land in certain environments a little bit before anybody else had gotten a chance to put some of those pieces of the puzzle together. And then I also think there's just a certain kind of authentic joy being captured, which still really speaks to people as well. FL

Redd Kross, Los Angeles, California. 11 May 1987. L-R: Roy McDonald, Robert Hecker, Steven McDonald, Jeffrey McDonald.