Step right up and prepare your ace notes—to commemorate the 20th anniversary of his 14th and 15th studio albums Alice and Blood Money, Tom Waits is pitching limited edition vinyl reissues of both LPs. Both releases possess beautiful translucent colors that befit their unique and complementary styles: blue for the somber and pouting-nymphet melodrama Alice and red for the drug-fueled, knife-glint thriller Blood Money.

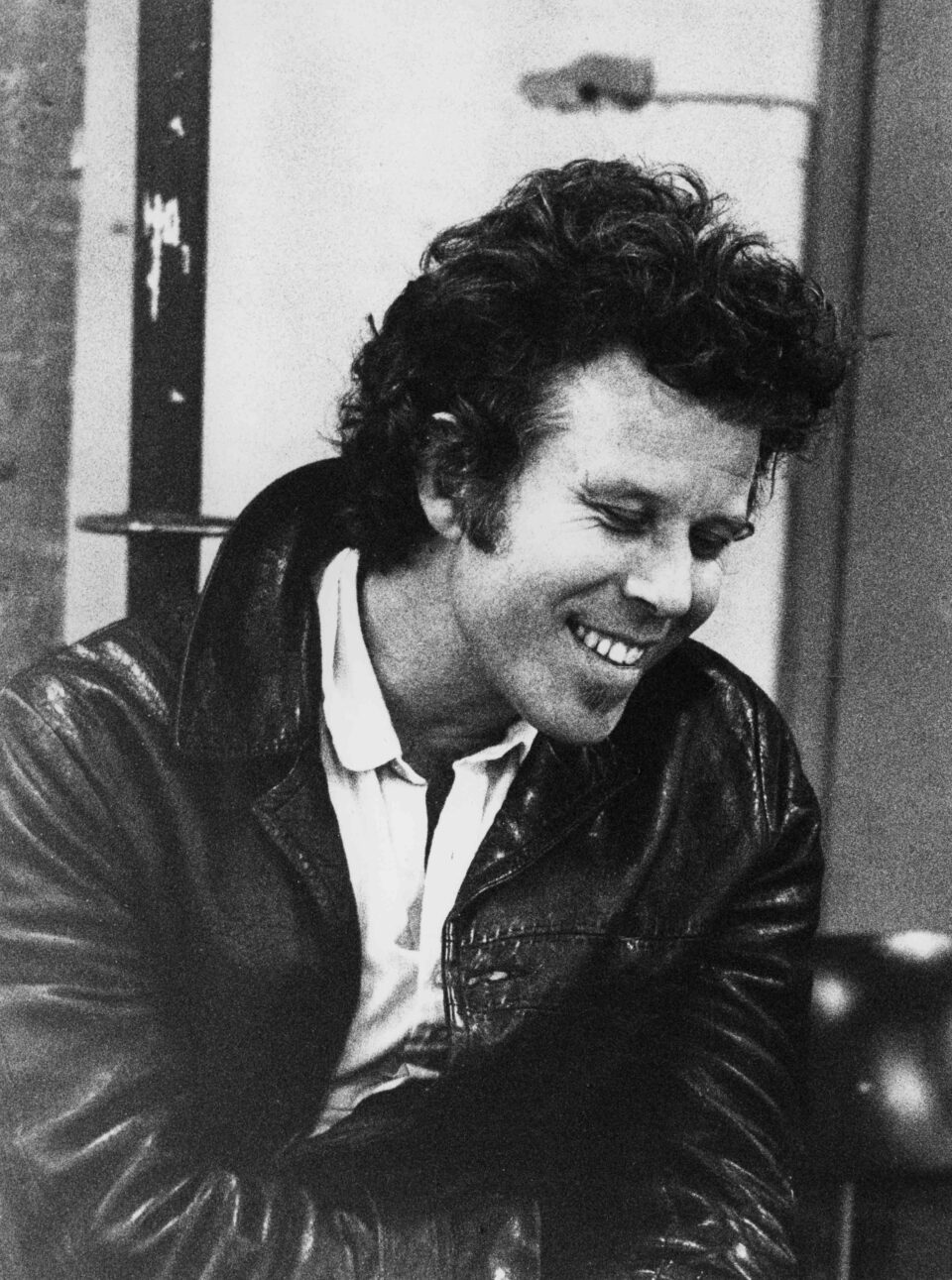

The two albums held up Waits’ fleabag entertainment to the light to showcase past angles on his artistic styles under new circumstances. The music industry’s carnival barker (“I thought high school was a joke,” Waits once quipped, “I went to school at Napoleone’s Pizza House”) folded up his big-top blues like a slice of pizza pie after 2011’s Bad As Me. Waits doesn’t partake in many interviews, tours, or new recordings these days, and although some have speculated that he’s constructing a new album, fans will need to patiently wait for Tom’s next winking press conference.

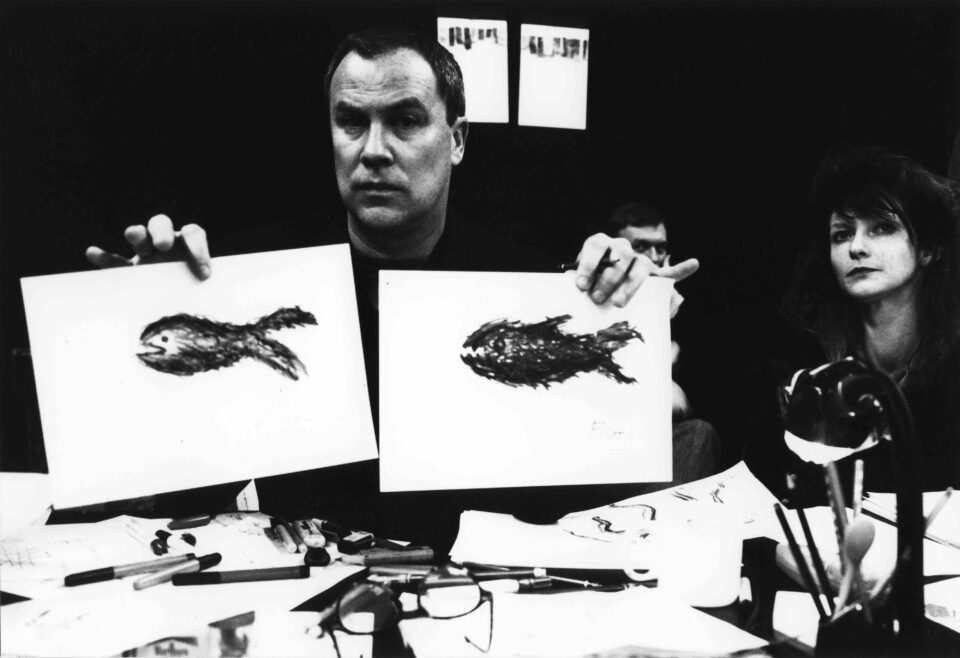

Meanwhile, we tracked down Tom’s longtime friend Robert Wilson to speak about their work together with Waits’ wife, Kathleen Brennan. The renowned artist is currently working on a new theatrical piece based on the life of Stephen Hawking with music by Philip Glass (with whom he collaborated on the iconic Einstein on the Beach) and choreographed by Lucinda Childs.

“I was anxious to do Alice after having made [1993’s] Black Rider with Tom,” notes Robert Wilson from Hamburg, Germany’s Thalia Theatre. Waits’ classics Alice and Blood Money were influenced by the stories around Wilson’s staged productions and were released three years after Waits’ hugely successful 13th album, the GRAMMY-winning Mule Variations.

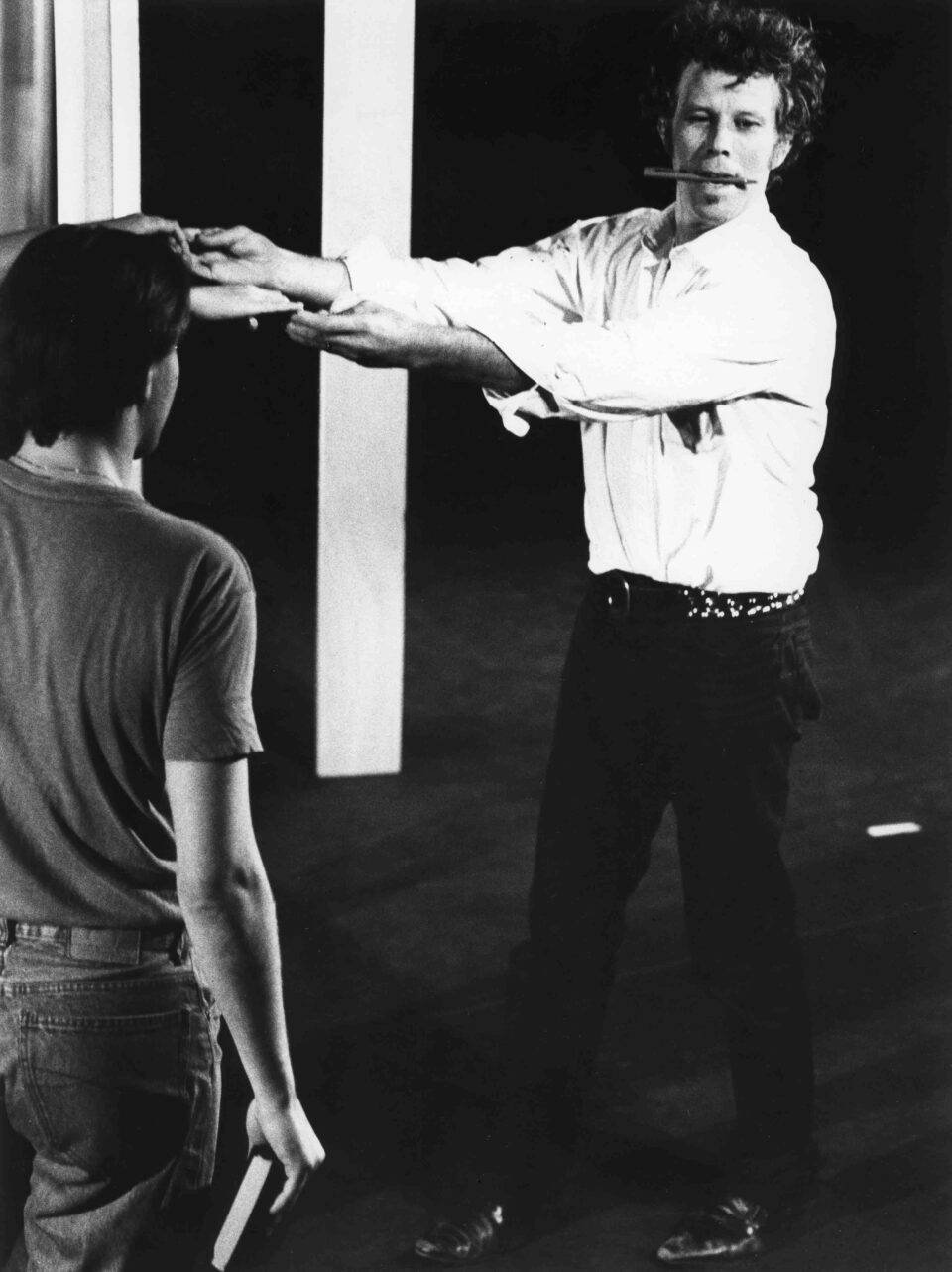

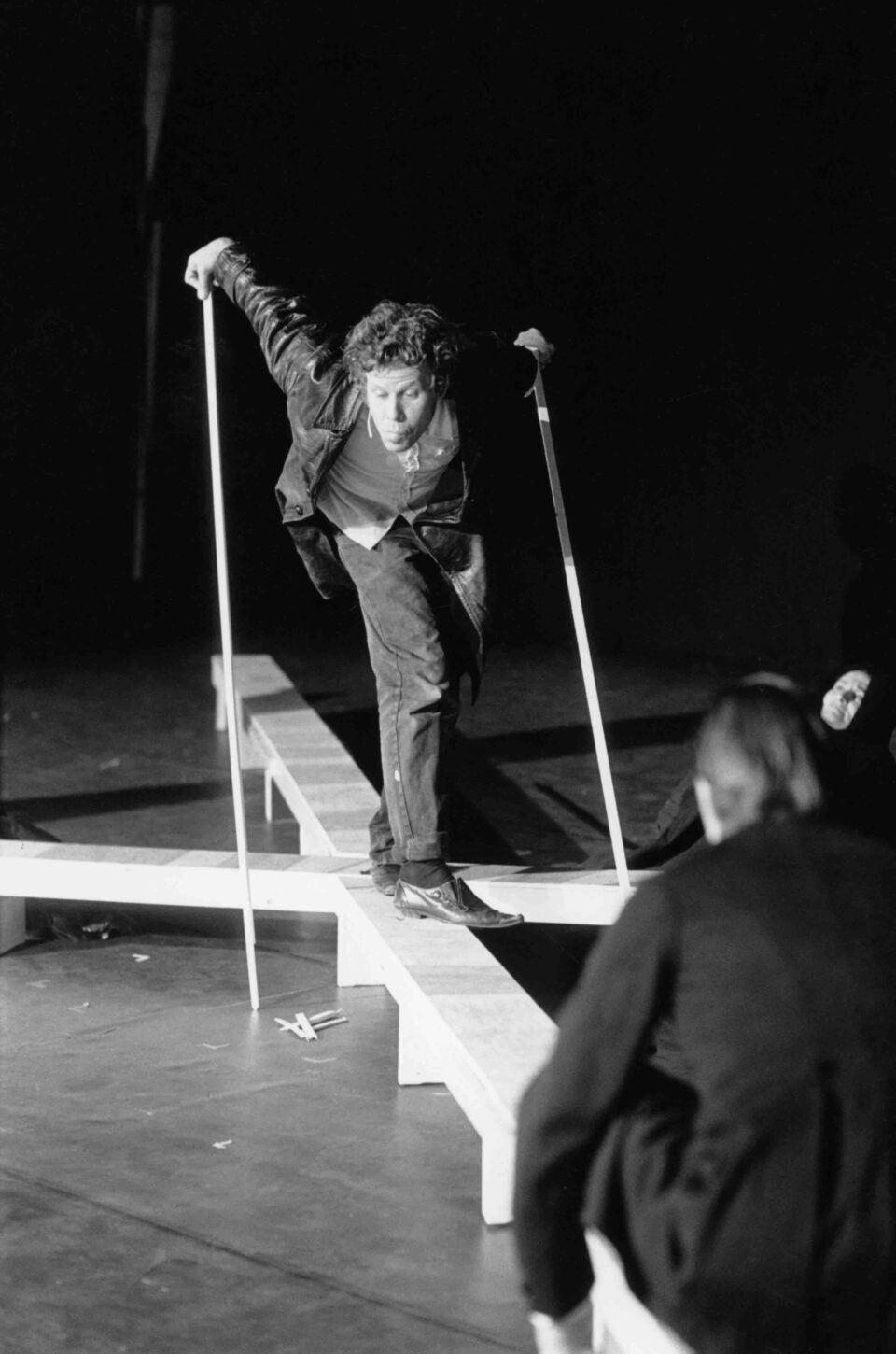

“I love to hear Tom Waits sing. His deep interior sense of music touches me and moves me deeply. Everything he does is extremely musical. Walking, playing an instrument—it is all dance.”

Wilson regards the two 2002 works very distinctly in his mind when looking back decades later: “Alice is much lighter, more transparent, like the reflections of glass. [Blood Money] has sharper edges.” His friend Waits also holds a special place in his memory, as the praise for his former collaborator tumbles out of him like luggage from the belly of a moored ship: “I love to hear Tom Waits sing. His deep interior sense of music touches me and moves me deeply. I love to hear him play piano, I love the sound of his voice. He knows his body extremely well. Everything he does is extremely musical. Walking, playing an instrument—it is all dance. I always saw Tom as Woyzeck.”

Blood Money darts between portraits of carnality and mortality like the eyes of a serial killer haunting a carnival. “Misery is the river of the world” after all. Based on the play Woyzeck, the theatrical piece was originally written by German poet Karl Georg Büchner in 1837 and inspired by the true story of a German soldier driven mad by outlandish military drug experiments leading him to drown his wife and humiliate her lover. Wilson had challenged himself with two of Büchner’s three total works and pursued the final piece with keen interest. Waits and Brennan penned the songs of Blood Money based on the production of Woyzeck, a third collaboration with Wilson that premiered in 2000 at Copenhagen's Betty Nansen Theater. The show later won the Danish equivalent of a Tony Award for Best Musical.

“Blood Money is flesh and bone, earthbound,” said Waits in press materials for this anniversary. “The songs are rooted in reality: jealousy, rage, the human meat wheel. They are more carnal. Kathleen and I are well suited to this material. She is hilarious, blasphemous, and ominous. I like a beautiful song that tells you terrible things.”

“Tom and I are very different, but we share a common sense of time and space. He was very interested in my pictorial sense of space.”

Turning back the dial a bit, it’s no stretch to agree with Wilson’s assertion about Tom being a modern Woyzeck when it comes to his live performances, where he resembles a Tin Pan Alley mutation of court jester, carnival barker, and a smoking Mephistopheles draped over black and white keys. Prior to the re-release, Waits shared previously unreleased live versions of songs on both albums, beginning with “All the World Is Green” from Blood Money and “Fish and Bird” off Alice. Incredible live versions of Alice’s “Table Top Joe” and Blood Money’s “God’s Away on Business” trailed shortly after.

Waits dancing, talking, and smoking onstage is where these songs from 2002 truly shimmer and shine. They gleam like the grill of a 1957 Chevrolet station wagon speeding down Route 66, or the gold teeth of a carnival strongman grinding for his daily take. Waits is the X Man, a fairground exclusive in the old-timey parlance. Wilson has a wholehearted predilection for Waits’ type of artistic brinkmanship with no room for any flim-flam and no hanky panky for any detractors.

Wilson and Waits first watered the roots of their relationship in their shared experience of living in Texas. “That is the blood of both of us,” he remarks. Wilson now lives in Europe, but his first home, Waco, is where he initially saw Elvis perform, a palpitating sight of raw sensuality that he couldn’t shake, similar to “the acoustic atmosphere of carnivals” from his youth. These are shared touchstones for both artists who grew up in post-WWII America. “Tom and I are very different, but we share a common sense of time and space,” remembers Wilson. “He was very interested in my pictorial sense of space.”

That sense of space reverberates throughout Blood Money’s soft and solemn companion, Alice. The album and avant-garde opera piece are based partially on the life of Alice Liddell, the girl who inspired Lewis Carroll’s 1865 classic Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. The opera was directed by Wilson for Hamburg’s Thalia Theater in 1992. It was the second collaboration for Waits and his wife Kathleen with Wilson—the couple previously worked with the director and playwright on the 1990 production of The Black Rider: The Casting of the Magic Bullets, which was formulated by Wilson, along with Waits and William S. Burroughs. Wilson describes the process of making the opera in a succinct fashion like an architect of art, “I made a structure of a work, an outline, and a drawing, so I could see the whole. From that, I worked with Tom and William.”

“Tom’s singing touches all of us regardless of religion, politics, et cetera. We have a shorthand that works very well between all of us.”

The songs of Alice are dark and brooding affairs, drooping like a dewdrop rose in its death throes, but as rich as a silent film score—it’s “dreamy weather” after all. The record is plump with instrumentation—a brass section, pump organ, vibraphone, bass saxophones, and a string quartet fill out the range of sounds. Waits was sick of the same violins that sat on top of his ’70s work like an elephant, so the strings on this record are fainter than before and are more of an accent than a driving force throughout. Wilson sees Lewis Carroll’s story that inspired Alice as something “full of time…it is not timeless, but full of time.”

“Full of time” seems like an accurate description of the balanced works of Tom Waits and Robert Wilson on the conjoined twins of Alice and Blood Money. Wilson still keeps in touch with Tom and would be open to working with him and Kathleen “any time. Tom’s singing touches all of us regardless of religion, politics, et cetera. We have a shorthand that works very well between all of us.”

The best artists possess a strong level of abstraction in their art by not putting themselves into the light as much, but instead pushing unique characters from other times and places into the circle. We all look forward to the next characters Tom Waits may reveal under his musical big top. Pass the popcorn and stretch your legs if you want. This next number’s gonna make the hairs on your arm stand up like tombstones. FL