No one in the music industry could have predicted that a kid from Alberta wearing cherry lipstick and doing an Elvis impression would become the godfather of the millennial slacker revival, but Mac DeMarco defied the odds. Categorized as a “mini-LP,” DeMarco put out the 26-minute Rock and Roll Night Club in March of 2012, which he recorded in his then-home of Montreal. “It’s interesting because I did something that was really strange and that was the thing that all of these labels were like, ‘We want to put this out, this is cool, we can sell this,’” DeMarco explains over the phone from his studio in Echo Park.

Even though the music he’d been making prior to 2012—with and outside of his rock project Makeout Videotape—was a bit more gauzy and not as intentionally retro, Night Club felt like a marketable moment, and labels wanted to capitalize on it. “Even when I signed to Captured Tracks, they were like, ‘How many more of these Elvis albums do you have in you?’ and I was like, ‘Yeah, plenty, no problem!’ But I didn’t have any, so then I was like, ‘Hey, I’m gonna make a record that sounds more like my music.’”

DeMarco started his day by riding his motorcycle around Los Angeles. It’s the 10th anniversary of 2, his breakout album, which critics lauded as a groundbreaking and essential record in contemporary DIY indie rock before the genre became a catch-all term for anything existing outside the top-40, a time when playing 200 shows a year felt unhealthy, but could make or break an artist just clawing to survive.

But 2 wasn’t only a catalyst for a music industry that had merely flirted with bedroom pop beforehand, it sparked an evolution for DeMarco, too. “[2] felt more, at least musically, honest, or personal,” he says. “It’s funny, because I remember sending the demos to the label and being like, ‘These are my new songs,’ and they were like, ‘What the fuck is this?’ and I was like, ‘Shouldn’t have sent these demos.’” But once Captured Tracks heard the final draft of the record, no convincing was needed.

“I never thought I’d be able to do anything like this. I’m just a normal dude from the prairies in Canada. I’m sitting in my studio in my house in LA right now, and I got all these tape machines. It’s ridiculous!”

2’s impact blew the cult appreciation of Rock and Roll Night Club out of the water. DeMarco was finally on the map, critically and commercially, though the latter was often not as lucrative as the former, and his “small-time musician” label was coasting by the wayside. But before critics took note, DeMarco was playing near-empty rooms at 200-person capacity venues across North America. “I toured the States a couple of times, but no one would come to shows,” he says. “It didn’t matter, it was fun to go and do the shows. I never thought I’d be able to do anything like this. I’m just a normal dude from the prairies in Canada. I’m sitting in my studio in my house in LA right now, and I got all these tape machines. It’s ridiculous!”

The industry adopted DeMarco as its prized pupil at the age of 22. How could they not? He was a perfect embodiment of the success story it demanded. He was going to march to the beat of his own drum and make the records that scratched the creative itch rummaging in his brain. He once personified the playfulness of Jonathan Richman with the bravado of Pavement during their most raucous era, but now he’s mellowed out. That’s why DeMarco’s last record, 2019’s Here Comes the Cowboy, doesn’t hinge too heavily on keeping up with the antics of 2. Ten years ago, a song that repeated the line “Here comes the cowboy” with a backdrop of a single plucked chord would’ve been unsellable beyond a very niche market that probably didn’t exist yet. A ditty dedicated to a certain brand of Canadian cigarettes set to addictive, lo-fi psychedelia, however, was a different story.

DeMarco’s rise in 2012 doesn’t feel nearly as alien in the context of contemporary music. Artists whose MO is to troll their listeners and rake in streams from intrusive curiosity alone wouldn’t have a leg to stand on if it weren’t for DeMarco. His onstage antics—which, on any given night, would range from performing absolutely shitfaced to stripping down naked and climbing venue scaffolding—are pretty much absent from his modern-day sets. You can only show your junk to fans so many times before your age catches up with you, and the musician and person DeMarco has become reflects how he’s grown up in a very real and public way. That doesn’t cheapen the environment 2 was made in, though. It’s aged wonderfully, and feels indicative of a certain era in indie that’s now mass-produced.

“I wish I knew less 10 years ago. I think that not knowing what you’re doing, not knowing what a preamp does or what microphone to use, it can make a beautiful thing by accident, and I love that.”

On our call, DeMarco is still the same goofball he’s always been, trying on different accents to emphasize different parts of his stories—though he’s a bit more weathered now, 10 years and a thousand shows later. There’s a bit of retrospect lingering in the air, a momentary longing for the inadvertent magic born from just doing whatever the fuck he wanted. “I wish I knew less 10 years ago,” DeMarco says. “I think that not knowing what you’re doing, not knowing what a preamp does or what microphone to use, it can make a beautiful thing by accident, and I love that. I still try, in some ways, but, over the last couple of years I’ve become very involved with pro audio gear.”

2 was raw and unfiltered, but only a smidge messy. With a tape reel quality that sounds like a live show, the record found its footing but didn’t send DeMarco all the way to the moon. Not yet. Successor Salad Days would take him to places he’d never been before, but it was recorded almost identically to 2. “I used the same tape machine, maybe even less channels than I did on 2,” he says. “I had a new mixer and some new speakers, maybe some new synthesizers, but everything else remained exactly the same. Everything was pretty ramshackle. I had a very tiny apartment that I converted into this recording space. Right when I was finishing 2, my neighbors finally started knocking and being like, ‘What are you doing in here?’ I’d say ‘I’m sorry, I’m almost done, I’m sorry.’”

Once the songs of 2 hit DeMarco’s nightly setlist, most of them never left—even four albums later. “Cooking Up Something Good,” “My Kind of Woman,” and “Freaking Out the Neighborhood” have all remained just as integral to his on-stage presentation as anything he’s made since. “It’s funny because this year, all of a sudden, these festivals and places were like, ‘If you play some of those old songs, kid, we’ll give you a higher guarantee,’ like I’m some legacy act or something,” DeMarco says. “Like, ‘They never left the set, pal, so give me more money and I’ll do it.’”

But the endurance of 2 often rests on the shoulders of “Still Together,” a tender ballad about his longtime girlfriend Kiera that closes the record and every show, and “Ode to Viceroy,” a scintillating piece of hypnotic rock hellbent on telling us just how much DeMarco loved cigs in 2012. And for 10 years, they’re the only songs that have been in every one of DeMarco’s sets. The outro dialogue of “Viceroy” perfectly encapsulates the importance of 2 altogether: “There really is nothing quite like you.”

“It’s funny because this year, all of a sudden, these festivals and places were like, ‘If you play some of those old songs, kid, we’ll give you a higher guarantee,’ like I’m some legacy act or something.”

When 2 hit shelves, DeMarco was touring relentlessly, a practice he kept up until the pandemic hit. He’d take any gig offered to him, and he did that for years. But the parasocial relationship between musicians and fans has shifted in a much more digitized landscape. “Now, the way things have changed online, immediate and constant access is what people expect. Now, if they don’t have it, they’re like, ‘I bought your record, you’ve betrayed me, I invested in you,’ and that’s not how it works, I’m sorry. It’s almost like scarcity, or privacy—people are more enchanted by it, I think. Nobody does it anymore.”

In turn, DeMarco has become a relatively private person in recent years. He’s completely off social media, eons away from the days of his absurd penis-centric hashtags and Star Wars shitposts. It’s not that he feels the need to hide so much as it is that he doesn’t have anything left to prove to anyone. And, as it’s been emphasized with “Chamber of Reflection” and “On the Level” becoming popular TikTok audios in the last year, DeMarco’s music continues to find new listeners without him so much as lifting a finger.

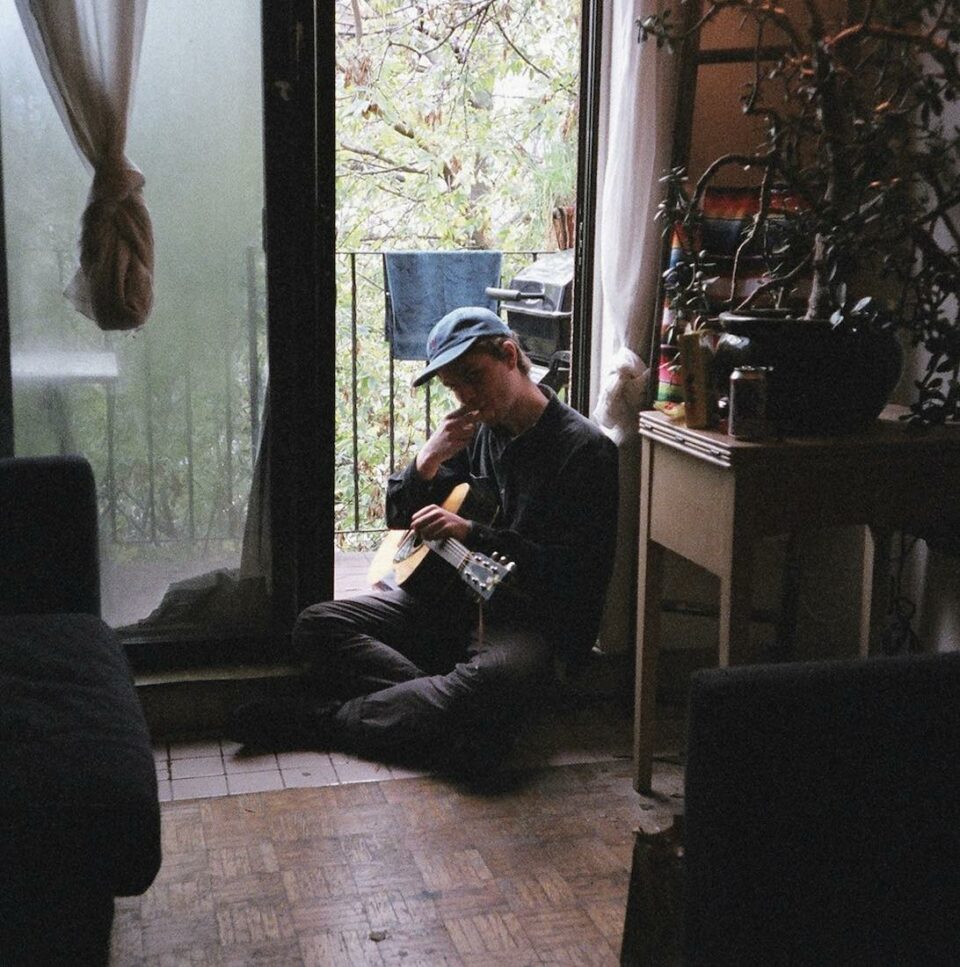

Mac DeMarco / photo by Adam Maresca

But he’s also never felt more in touch with the people he sings to every night. After playing gigs, he’ll stand outside of venues for hours, talking to people and taking pictures with anyone who wants to come by and say hello. At the end of the day, he’s just Mac DeMarco. And to him—and to so, so many others—that’s more than enough. “I was thinking about this as I was riding my bike earlier. I’m still willing to be whatever anybody wants. My thing for years was like, ‘This isn’t a stage name, the songs aren’t make-believe—this is just me, you can have me, here I am.’ And that’s still true. I still write songs like that. But I need some time or space for myself. If you want to be angry at me, if that helps you, go ahead. If you don’t need me at all, that’s fine. I’ll be over here if you do.”

The crowds at Mac DeMarco shows are filling up with new fans who are late to the party but just as eager to share a night of communion and inside jokes with longtime Pepperoni Playboy ambassadors. He cites a particular performance of “My Kind of Woman” in São Paulo, Brazil, where he couldn’t hear anything on-stage because the fans’ singing was drowning everything out around him. Out of all of the shows he’s done, that’s the one that immediately pops into his brain when he considers what legacy the tracks of 2 hold for him a decade on. “I’ve played these songs hundreds of times all over the world,” DeMarco says. “I always say, too, they’re not really mine anymore. It’s been that way for a long time.”

“I’m still willing to be whatever anybody wants. My thing, for years, was like, ‘This isn’t a stage name, the songs aren’t make-believe—this is just me, you can have me, here I am.’ And that’s still true.”

It’s 2022 now and DeMarco is no longer punching upward like he was in 2012. He’s comfortable with his place in life, more than happy to kick back and listen to Frank Sinatra and video game soundtracks in his studio that he rarely uses nowadays. On the walls behind a cluster of synths, pianos, and computers are mementos he’s collected over the years: a cue card from a talk show appearance, trinkets gifted to him from fans, a copy of Playboy with Marge Simpson on the cover. He hasn’t made much music there since Here Comes the Cowboy. Instead, he looked for inspiration by recording an entire album in his car, family members’ homes, and in motel rooms as he drove across California and up into Canada during the pandemic. The sparseness of Cowboy might have initially signaled that DeMarco was softening out and winding down—that he’s as far away from the world of 2 as ever—but in actuality, he’s just not that interested in upgrading.

“I don’t really care about, like, ‘Oh, this delay pedal is amazing.’ I’m interested in, ‘This is an acoustic instrument that makes a real sound in the real world. The real sound and the real world is influenced by what kind of room you’re playing it in,’” DeMarco says. “It’s like, ‘Well, now I’m in a very strange little motel in Crescent City, California, and I wonder how the drums are gonna sound in here.’ And I get a kick out of that, be it good or bad. It sounds like that hotel room in Crescent City, and I think that’s important.”

The pursuit of happiness in music for DeMarco is not one of monumental financial success, but one of an unrelenting curiosity—regardless of whether or not his interests align with those of the industry. Though he doesn’t think he could make a record exactly like 2 again, he’s not done tapping into what got him excited 10 years ago: The rawness of music-making that so often eludes artists who’ve got more than enough means to play it safe. That’s what 2 was, and is, all about: making sounds that defy the limitations of what you’ve already done. DeMarco’s chords sound much different now, but the hopeful energy of what a song or an album of his can become remains magnificently the same. FL