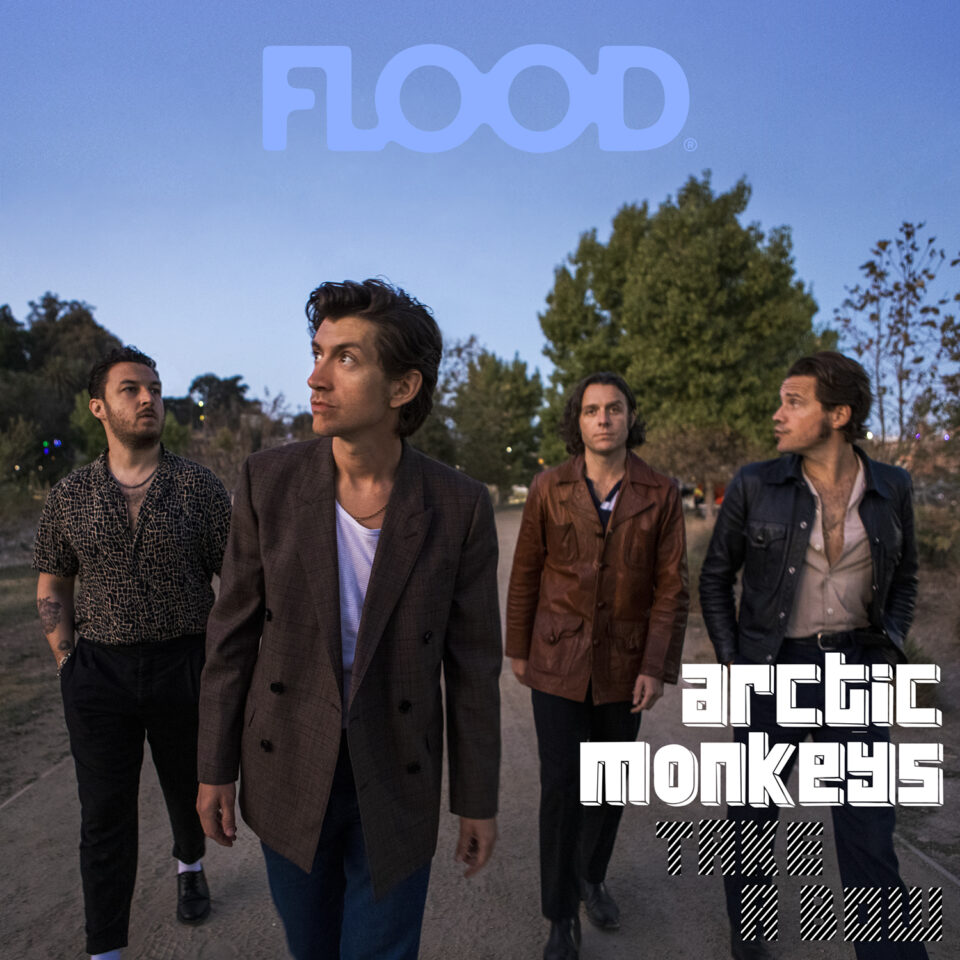

“What a death I died writing that song,” Alex Turner proclaimed in the second verse of “The Ultracheese,” the closing song on 2018’s Tranquility Base Hotel & Casino. A lot has changed since then, and the last two years have sparked a lot of rebirths. Arctic Monkeys know a thing or two about that, as the Sheffield quartet has gone through many eras since their inception in 2002 and their debut album, Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not in 2006. The once-giddy teenagers in tracksuits erupting onstage 16 years ago eventually became crooning greasers with oiled hair and leather jackets, before settling into the tinted sunglasses, slicked-back hair, and rolled-up sleeves persona they’ve fully embraced lately. But the isolation Turner sang about in 2018, under the guise of a rock god vacationing on the part of the moon where Apollo 11 landed, has grown timeless and undefinable by any particular album-accompanying aesthetic.

On their seventh and latest LP, The Car, the band has undergone another transition. At times, the record sounds like an incubation of everything they’ve accomplished so far. But it’s not so much a victory lap as it is that all of the roads they’ve traveled for 20 years have now become one. After releasing five albums in seven years, it’s taken the band nearly 10 to make two more. Turner recognizes that, and sometimes wonders if he could get back into his productive headspace from the Humbug years. “Everything we’ve done recently seems to have taken a long time to complete,” he says, chuckling. “I guess there’s other factors involved, but [Loren Humphrey and I] were saying, ‘Wouldn’t it be great to try and do something in a week?,’ kind of in the spirit of how I used to.”

“I think there is still some of that band on [The Car], the ones who did the riffy stuff 10 years ago. It’s difficult to completely take that off the table.”

When the band made their long-awaited return to the forefront of rock music in 2018, Turner had ditched his Outsiders costume for a shaved head and tinted shades, sat down at the piano, and spun webs of hubris and daydreams. That lounge-singer persona Turner embodied is still there on the new record, but paired with other checkpoints in the Arctic Monkeys timeline, like the ballroom waltzes and string movements he composed for the 2010 movie Submarine, or the distortion tricks from 2013’s AM. “I think there is still some of that band on [The Car], the ones who did the riffy stuff 10 years ago,” Turner adds. “It’s difficult to completely take that off the table.”

Turner is at his best on The Car. His vocal range, a patented croon gliding into a captivating falsetto no longer underused, is fully fleshed-out as evidenced by the band’s recent performance of “Body Paint” on The Tonight Show, where Turner employs a specific grandeur in his onstage mannerisms. He’s an acolyte commanding the stage, and a bravado pours out of him, one of sensual and undeniable color even at the slightest twitch in his supersonic hips. But when he talks in private about his own work, he’s patient and takes as much time as he can to fully articulate what the work means to him. A full arc of personhood like that, in which there’s as much theatricality present as there is generosity, is a wealth Turner gleans across his records.

What makes The Car so different from something like AM or 2011’s Suck It and See is how Turner approaches the conceptual side of his own creativity. The algorithm of an Arctic Monkeys album now blurs the lines of its own tracklist, the throughlines extending beyond the limitations of one singular performance. “I stopped putting up those boundaries quite a long time ago,” Turner says. “For a while, I’ve been trying to get ‘the thing’ across over the 10 tracks or the 45 minutes, rather than try and do it in three. I’m not suggesting that that’s how it should be forever and always, but this time it seemed to go that way.”

In turn, The Car’s wholeness pulls in the same direction, the continuity building from track to track. Themes repeat in the lyrics like a connective tissue, but the record’s soul is held together by the feelings the arrangements evoke, which will be different for every listener. The music takes many shapes throughout, much like the early sketches of Whatever People I Say I Am. In the beginning, Turner wanted that record to tell a story across the timeline of one weekend, lyrically, with arrangements that fluttered across the large scope of the band’s interests. “I do feel like as time has gone by I’ve hopefully done a better job of joining up those dots,” Turner adds.

The dots arrive on opening track “There’d Better Be a Mirrorball,” which begins with strings, piano, and a harpsichord that feel very much like an intentional extension of where Tranquility Base left off. It’s only momentary, though, as Turner and company ooze quickly into a Funkadelic-esque odyssey on “I Ain’t Quite Where I Think I Am.” But Turner is a dramatist, a sonic thespian unafraid of threading his own restlessness and desire through 40 minutes of music. He sings of yesterdays and forgotten pleasures. The car on the album’s cover is just a MacGuffin; the mirrorball Turner yearns for is also a chandelier, a hotel notepad with a lump sum written on it, and a long goodbye.

Turner wrote most of Tranquility Base on the piano, because the guitar had lost its ability to give him ideas. That wasn’t entirely the case with The Car, as some songs were recorded while Turner was, as he phrases it, “stood up” playing the guitar, though he’d still sit on his piano bench and look at the possible directions of each track from there. The real magnitude of the band’s shift in sound comes, however, through Turner changing his approach to building the architecture of the songs themselves. “I think the main thing that’s changed in the last 10 years, versus the period before that, is I’ve been using the studio as part of the writing process, sketching out ideas for songs and recording them as it goes along,” he says. “How I was doing it before I had that space was writing on an acoustic guitar, or putting it through the rehearsal room, rather than the demo-recording, studio phase. I feel as if it’s had more of an effect on the way the records are coming out now, or at least as much as the introduction of the piano.”

“In those first few years, if somebody got a Moog synthesizer out, we’d be like, ‘What the fuck is going on? Are we gonna play this tomorrow night?’ We put limitations on [ourselves], certainly for the first two records.”

The songs on The Car are also a lot more collaborative than those on Tranquility Base were. One song stemmed from an idea that guitarist Jamie Cook had, and touring guitarist and keyboardist Tom Rowley even snagged a few co-writer credits after giving Turner some input during sessions. “I wrote around other people’s ideas a bit on this one,” Turner says. “On the first few records, I would always work on the lyrics, largely by myself and then bring them into the rehearsal room. That’s how the process worked then.” Writing around The Car began with the instrumental at the beginning of “Mirrorball.” The song’s story reacts immediately with those opening phrases in the music. “I figured out how to bridge that [opening phrase] into something that could be a pop song by the end. I feel as though the lyrics now take a lot more cues from what’s going on musically,” Turner adds. “And maybe, once upon a time, that was closer to the other way around.”

On Whatever People Say I Am and 2007’s Favourite Worst Nightmare, the lads weren’t thinking about the recording process. Instead, they were giving more consideration to how they would play each song live. “The criteria for the recorded version, when you eventually got to that point, was to make it sound as much like it did on the stage as possible,” Turner says. All of that’s changed, though. The band’s tenacity is strong enough to build a live set around compositions that are heavy sonic detours from previous work. “I think you arrive at that conclusion over time. There’s a confidence that didn’t exist then, that you’ll find a way to translate what you do on the records into something that may or may not fit into a show,” Turner adds. “I remember in those first few years, if somebody got a Moog synthesizer out, we’d be like, ‘What the fuck is going on? Are we gonna play this tomorrow night?’ We put limitations on [ourselves], certainly for the first two records.”

Arctic Monkeys have remained such a totem in popular culture since then that it’s hard to believe their first record’s success is partially due to the influence of MySpace. “I remember playing a show—I want to say it was in January 2004, in Sheffield—and word had gotten around about the band and people who’d come to see us from out of town,” Turner says. “I think we had a CD that had been passed around at some other shows before that. I remember that being quite overwhelming, the first time I can remember people knowing our songs and feeling as though they had a connection with them.”

This past summer marked 20 years since Turner, Cook, Matt Helders, and Andy Nicholson (who’s since been replaced by Nick O’Malley) first struck up the band, and the anniversary has been on Turner’s mind. Before they had a record deal they were broken up for a period and, when they reconciled, their goal didn’t extend too far beyond just going out and playing the small batch of songs they had booked. “I remember that in the beginning, to do a gig was the extent of our ambitions, to be quite honest,” Turner says. “Just getting on stage seemed pretty far out. Once we got through that first show, the whole thing shifted and I realized that I wanted to make this happen. Then, over the next few years, it got brought into focus.”

“I remember that in the beginning, to do a gig was the extent of our ambitions, to be quite honest. Just getting on stage seemed pretty far out.”

Songs from Arctic Monkeys’ first two decades, like “505,” “I Bet You Look Good on the Dancefloor,” and “Do I Wanna Know?,” have never left the setlist. Though the band has tumbled through different compositional habitats on tape, the songs always take different shapes once they cross the threshold of a crowd. As the guys have grown older, so have their performance styles. The rowdy stuff of old gets a new, more-composed sheen. The newer material explodes into wider versions once they’re played to a venue of hundreds. “I can’t lie, I think sometimes when we’re playing the old [songs], I do feel myself taking a moment to have a deep breath before we set off into those,” Turner says. “It’s been a while, anyway, since we played the way we did in 2005. The songs tend to all end up in a different place than where they were at the time the record was pressed. I think that keeps it exciting.”

During their recent show at Kings Theatre in Brooklyn, the band played “Mirrorball” and “Body Paint” for the first time. With a catalog as diverse as Arctic Monkeys’, it’s hard to gauge how the band’s large, still-growing fanbase will receive new work. Naturally, it was all copacetic, and the material is beginning to take on a life of its own onstage with an ensemble wider than what the band could fit into The Car. “I think things tend to become more exaggerated versions of themselves,” Turner says. “When we played ‘Body Paint,’ which gets a bit Mark Ronson-y at the end, onstage the other day under the lights, suddenly it became more robust. The energy in the room when we were playing [‘Mirrorball’] at the top of that show, it was quite remarkable. It made us all sit up straight.”

“I can’t lie, I think sometimes when we’re playing the old [songs], I do feel myself taking a moment to have a deep breath before we set off into those.”

Tranquility Base toyed with the idea of rock operas, sci-fi, and meta-contextual strokes of detachment. It was a colloquial achievement, as Turner coiled his way around a gilded thesaurus. The record was sleazy, futuristic, and absurdist—a far departure from the bluesy, dive-bar world of AM, where Turner and the band lampooned fantasy in the name of Elvis aesthetics and retro fuzz tones. The song suite of Tranquility Base was where Turner could fully embrace being a disciple of David Foster Wallace’s “strange objectless unease.” At the heart of every song were momentary lines that harbored great, prismatic proclamations of love, paranoia, and sorrow, each enveloped by these mountainous, incomparable fits of language that made you feel immense, discernible memories within yourself.

But The Car is most often quietly beautiful, with a sparse melancholy only Turner can translate into such formidable art. Even when Turner’s prose meditates on jet skis shot in CinemaScope, or a Lego movie about Napoleon written in “noble gas-filled glass tubes,” there’s a new kind of lonesomeness in his delivery. It’s as if everyone’s holding festivities he wasn’t invited to. Four years ago, he was at a moon resort, dissociating with his own qualms about the American Golden Age permeating 238,000 miles away. Now, back on Earth, he’s wrestling with the fleeting affectations existing just beyond his grasp.

“The whole record is a long goodbye, in some way, shape, or form.”

In 2019, as he began working on The Car, Turner was reading a lot of Raymond Chandler books and stepping into the mind of the author’s most famous character, the private eye Philip Marlowe. Turner’s interest in Chandler’s The Long Goodbye and how, as he puts it, the “whole record is a long goodbye, in some way, shape, or form,” isn’t a signal that the band’s end is near. Instead, the “goodbye” that awaits us at the end of “Perfect Sense” is Turner’s idea of letting go of the yesterdays he eulogized in “Mirrorball.” In reality, there’s a sense of hope lingering for Turner and the band. The shows they’re playing now feel different than they did four years ago. After 20 years together, Arctic Monkeys are shifting their focus on where the songs will take them next. “There’s something untapped, in the distance, that we’re moving toward,” Turner adds.

The way Arctic Monkeys presented themselves in 2013 during the rollout cycle for AM was perpendicular to the landscape of social media at the time. While people were starting to cultivate intimacy online, sharing floral graphics with “Let me be your coffee pot” pasted over top of them on Tumblr, or discovering hordes of like-minded fans within private Facebook groups, Turner and company were dousing themselves in a rugged, sensual retroness signifying some utopian, otherworldly freedom from long ago.

But now, as audiences have grown older and matured alongside the band, something has changed. Turner is writing songs with a sense of detachment, romance, and wonder that’s widely understood and felt, which is what makes The Car such an important record in the band’s history. He’s feeling a bit morose and trying to navigate his way through it with poetic meanderings that conjure vivid imagery many of us haven’t seen in a long time. It’s not all cuddles in the kitchen and puppets on strings anymore, but a chapter of popped travel-sized champagnes and stackable party guests that’s quickly winding down. And surely there’s a mirrorball awaiting all of us when we reach our destination. All we need to get there is a car, a shave, and a bit of sleep. FL