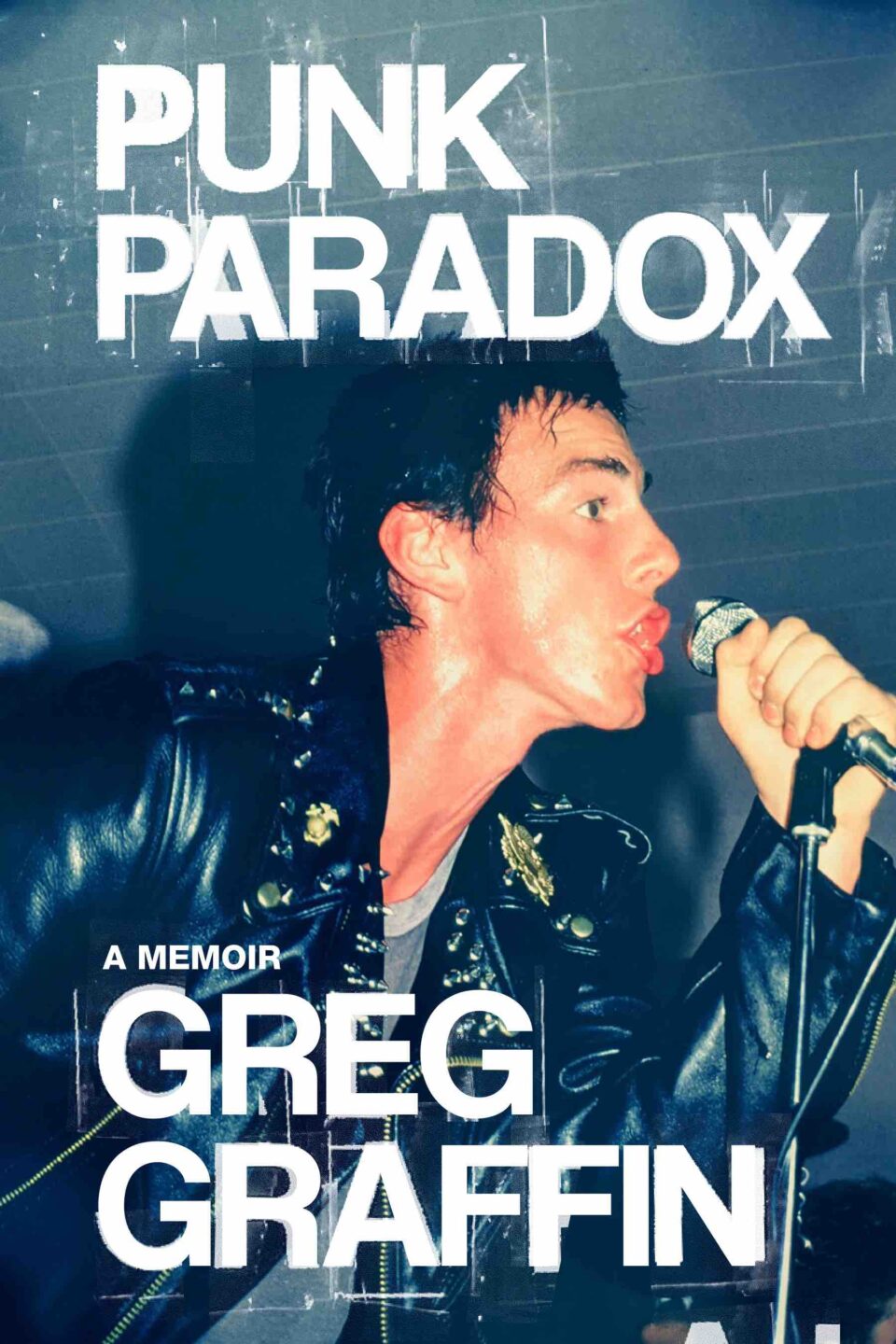

Greg Graffin is many things to many people. To punk fans, he’s been the frontman of the pioneering act Bad Religion for over four decades. To his students, he’s a professor who utilizes his PhD in zoology to lecture about evolution. To his family, he’s a father and husband who grew up in a family of academics that he aptly refers to in his new memoir as “Graffin University.” Punk Paradox is his attempt to reconcile all of these seemingly disparate aspects of his identity into a cohesive whole, and the result is a story that, unlike most memoirs of the nascent punk era, favors self-reflection over sensationalism.

Punk Paradox also acts as an excellent companion piece to Bad Religion and Jim Ruland’s 2020 book, Do What You Want: The Story of Bad Religion (“You can use Jim's book as a skeleton of the events in the band and my book as the guts and connective tissue,” Graffin explains). That said, even if you’re not familiar with Bad Religion or Graffin’s life, Punk Paradox is a captivating character study of someone pursuing his passions in seemingly contradictory fields and staying true to himself and his own inner compass. Ultimately being able to experience that journey in detail as a reader may be Punk Paradox’s greatest gift.

We spoke with Graffin about his approach to writing the book, connecting the dots between different facets of his life and career, and more in the Q&A below.

I’ve always been aware that you were an academic, but this book was fascinating because it really explained the genesis of how that evolved.

For me it’s second nature because it’s my life in a nutshell. But I was conscious about letting the reader know that your cultural milieu that you’re brought up in goes a long way to defining your later course in life. Even though we like to think when we’re younger, “Fuck that, I’m not anything like my parents, I’m going against everything they taught me,” the truth is you can’t really escape it because your values are shaped without your knowledge by those very early impressions. So in the book I tried to write about those early impressions: The smells of the libraries at universities, hanging out in abandoned classrooms while my parents were having faculty meetings. That kind of stuff was happening before I was even conscious that I was being shaped in any way.

So to go into this punk genre of music and write about academic subjects didn’t feel like a stretch to me. It just felt like that’s the way to fulfill, as I say, the dictates of Graffin University, which is where I was raised. In order to do a memoir in general—or a memoir like this, I should say, because I wanted it to be a more literary memoir—I would implore any readers out there to try and summarize the central spirit of your family. In my case it was a university, so I think that’s the way our households were run.

“In order to do a memoir like this, I would implore any readers out there to try and summarize the central spirit of your family.”

Another thing that’s really interesting about the book is the fact that you didn’t realize how bad the drug use was with other band members due to the fact that you were pursuing your graduate degree on the other side of the country.

I would put it this way: Academics really do live in an ivory tower. I was training to be one of those ivory tower intellectuals and one of the things about the ivory tower is that it’s perfect. The really cool professors try to downplay that, but the fact is the ivory tower is unassailable, and that’s why the aloof professor stereotype persists: because professors are really good at crafting a life of perfection. But in order to be perfect you have to reduce other things and get rid of the noise and pretend that the ivory tower is actually attainable by everybody, which it’s not. In fact it’s not even attainable by any professors, but that’s an ideal that they strive for.

Now in striving for this ideal, what you actually are is really out of touch [laughs]. You’re training to be really out of touch with what’s going on in the world, and that’s how I would explain my situation in graduate school in respect to things like addiction and struggling with substances. I was just out of touch completely. I didn’t understand what it was like, and I also didn’t understand the depths of really life-threatening conditions that it could bring with it. As teenagers you’re resilient, and even though it’s going on all around me, I just figured, “These guys are experts, they’ve been doing it their whole life, they know how to handle drugs and alcohol.” In the ivory tower there’s no such thing as being out of control, there’s no such thing as not knowing your own limits.

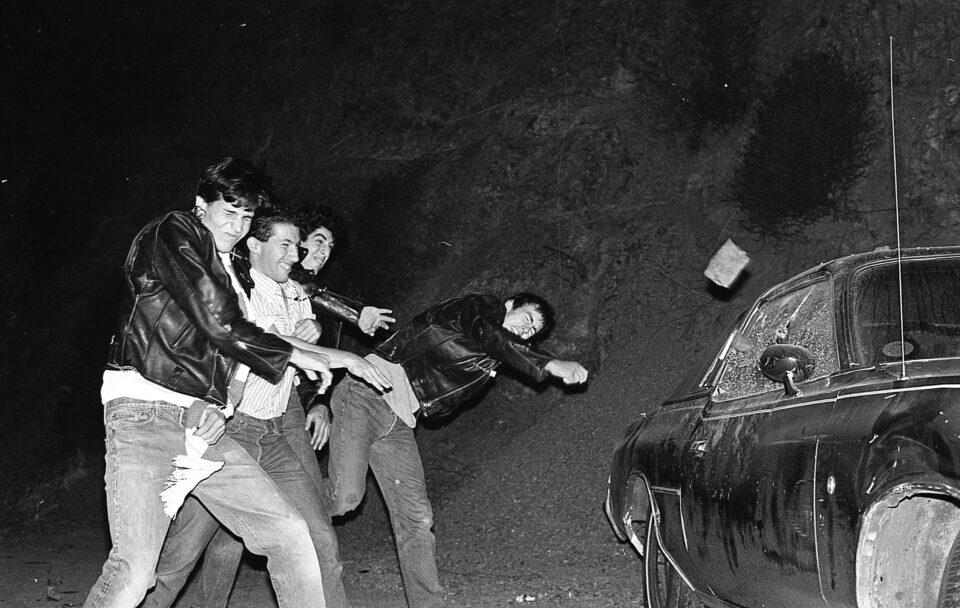

Bad Religion, circa 1980-81

What was it like going back over your life in order to write Punk Paradox?

The process of living it was probably a lot more harrowing than I would let myself admit at the time. No one is an expert at writing a memoir. It’s an exercise of choosing from your own life. Your life is full of multitudes of possible stories, and your job, if you want to communicate it in a memoir, is to choose one of those trajectories and try to give it some shape. So why are so many memoirs based on tragedy and redemption? Because the tragedy or single event in your life dominates your memory, so you choose that as a memoirist and you focus on it. That’s why there are so many drug memoirs or overdose memoirs where they talk about how they deal with that tragedy.

“Life is a lot more interesting if you can present it as a kaleidoscope, and the really thoughtful person is someone who can take those multifarious events and shape them in a way that other people can identify with.”

That’s one story in a life that has a multitude of possible stories. Honestly, I think life is a lot more interesting if you can present it as a kaleidoscope and something that has numerous events, and the really thoughtful person is someone who can take those multifarious events and shape them in a way that other people can identify with. I think that’s a better explanation of what I was trying to do, because there’s not one central tragedy. Yes, there are tragedies along the way, and I detail them in the book, but I don’t dwell on them in order to redeem myself of those tragedies, because I just don’t believe that makes for an interesting story.

So I had to go through the attic, find a bunch of photographs, remember what it was like, and do a little digging emotionally in order to talk about them. But ultimately all of them surrounded this evolution of a larger purpose that was defined by the first generation of Graffin University, which were my parents, who had to start anew. They infused us with those values, so to make the kaleidoscope consistent with those values I think is a really interesting story for everybody.

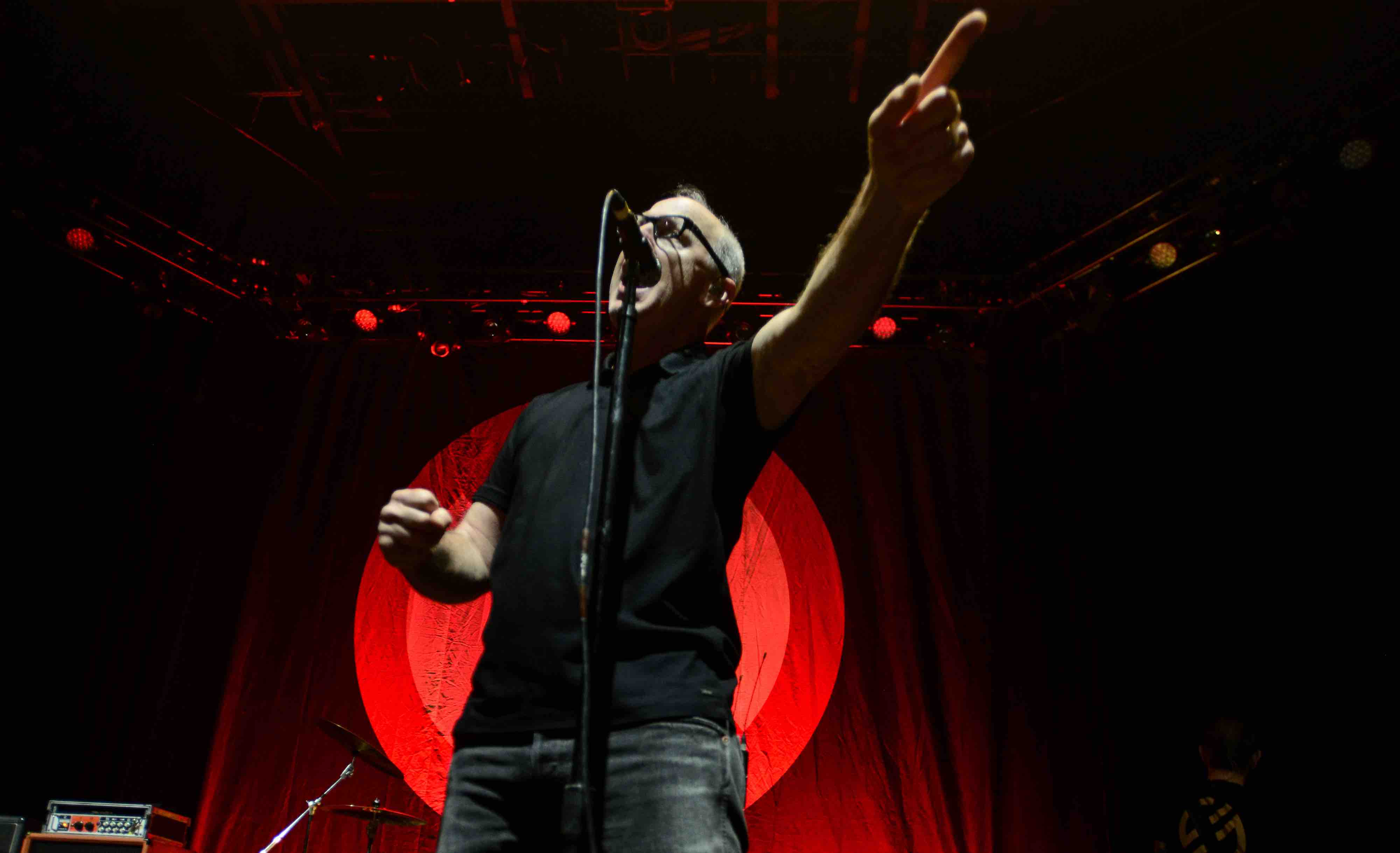

photo by Per Schorn

In the book you say that you thought blink-182 was NOFX the first time you heard them. Is that true?

[Laughs.] Yeah, that’s an absolutely true memory that I had. I mean, basically everything in the book is from my memory, but that’s something that struck me that I never forgot. When I first heard blink-182 on the radio, I thought it was Fat Mike because Mark [Hoppus] was trying to sound like he was on Fat Wreck Chords at the time.

Your book ends after Bad Religion’s co-founder Brett Gurewitz reenters the band and you make 2002’s The Process of Belief. Why was that the place to end the book?

The book was long and I wanted to focus on the most upheaval in the band’s history, and the most upheaval occurred during those times that Brett left and then came back. Then after he came back we entered into, as I say in the book, a long period of summer touring and a record every couple of years, which really persists until this day. I haven’t even seen the finished copy but it has photographs in there and the last photograph is a picture of when we did The Roxy show last year. We did a streaming event, and so I use that as the last photograph because that brings it right up to the present day.

“If you’re interested in trying to define the culture to which you belong, you should look at it as a journey, because the endpoints, both origin and extinction, are unknown.”

The book put so many things I didn’t really understand into context, like how how you ended up working with Todd Rundgren—all of these things that seemed so random to an outsider now connect.

That’s really great because it’s presented as random because it requires a book of this length to unravel the details. But it actually makes a lot of sense, especially given the fact that I really appreciated not just Todd Rundgren but also Ric Ocasek as creative collaborators, because Brett played that role. We were collaborators and when he left the band there was a big void not only in songwriting but in making the records.

When it comes to the mission statement of the book, what do you hope the reader walks away with after finishing it?

That’s funny because I never thought of a mission statement. That would be a mission statement for my life. I wouldn’t call it a mission statement, I would just say what you’re left with is that if you’re interested in trying to define the culture to which you belong, you should look at it as a journey, because the endpoints, both origin and extinction, are unknown. FL