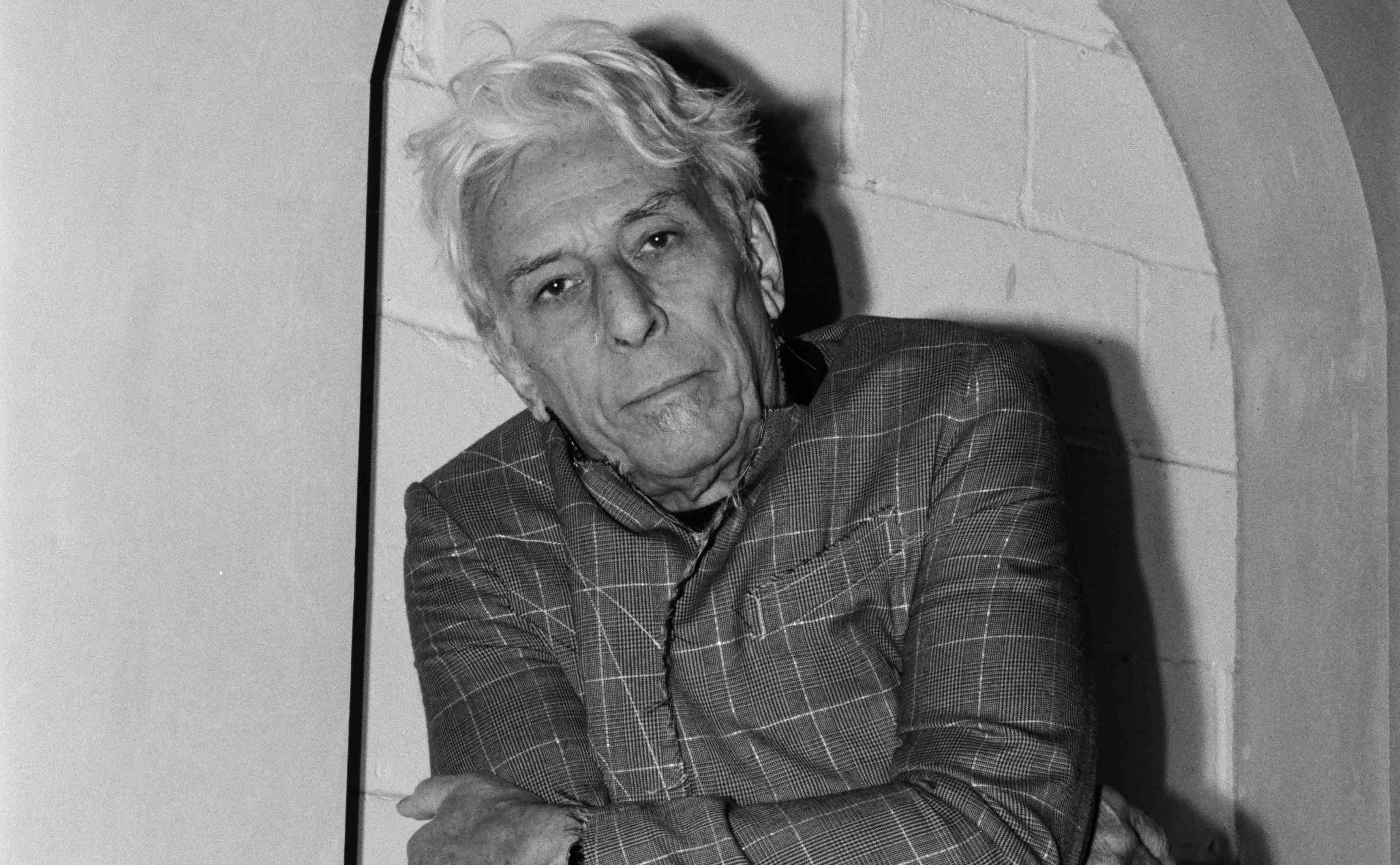

John Cale is about to release his 17th studio album, Mercy. Gone here are the days of droning bows—Mercy is a synth record overcast by the brooding, dark oeuvre Cale has long been cultivating. If you believe there’s a menacing backdrop to his screeching electric viola runs in The Velvet Underground’s “Heroin” that speaks to something greater and stranger than what transpired in Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable, then the pulsing beat and air-locked keys in a song like “NIGHT CRAWLING” may feel apt for a smog-riddled, painstaking render of a dystopian Los Angeles.

Fifty years ago, Cale was working primarily with the bass guitar, viola, and piano. On Mercy, he gives a lot of space to the building of an ominous world through electronic synthesis. “There’s a lot of magic in synths and the way that melodies come at you with whatever colors are available to you,” Cale says. “By the time I got into the synth, I was really entering the world of hip-hop and the rhythm was more important than anything. Getting a groove going was the very first thing that you did.” His love for the genre makes sense after learning that he’s particularly enamored by Earl Sweatshirt, an artist whose abstraction obliterates the notion that a song requires a verse, bridge, and chorus, much like Cale’s own musings over time.

For years, Cale has mulled the themes of alienation and grief, but those considerations are at their most immense on Mercy. It’s no surprise that the past half-decade is weighing on Cale now, much like the rest of us. On “TIME STANDS STILL,” he ponders what forlornness arises through cycles of political, natural, and self-destruction. The calamities of the present are footnotes accumulating in Cale’s long history of responding to a multiverse of pain, each forming different shades of his own creativity. Since his childhood, Cale has developed a keen eye for textural limits and has made a career overflowing with improvisation born from a meticulous study of classical music that reckons with modernity.

To be somebody who dares to extemporize through emotion or exploit the barriers of musical scale, you must first be fascinated enough by the human condition to probe its capabilities. Cale is in that domain, as his work of boundaryless improv stems from great articulations of emotion, and Mercy asks listeners to feel everything beyond the bloat of chart-topping bubblegum sheen. The foreboding noise across the record is not an aesthetic, but a thematic companion. Even the love song “NOISE OF YOU” challenges a listener’s expectations of how to translate romance electronically.

“By the time I got into the synth, I was really entering the world of hip-hop and the rhythm was more important than anything. Getting a groove going was the very first thing that you did.”

The most intriguing part about Cale’s artistry is that he’s seen the world enough times over yet still has so much left to say about his interaction with a sonic ecosystem that’s always expanding. When I ask him what parts of humanity are left for him to think about, his answer pokes fun at the sometimes-scholarly catch-all that is so often used to describe his esoteric art: “I guess you could say, with a chuckle, that Shakespearean experiences have not really entered into my realm yet. It’s a little grandiose to say it that way, but if you want to have a laugh, let’s have a laugh.”

Cale’s career is not Shakespearean so much as it is one of human-made magic. Many of his contemporaries also fell in love with Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock” in the mid-’50s and decided they wanted to be showmen, much like how, as Brian Eno once said, everyone who bought the first Velvet Underground record started a band. Though it might not have seemed like an obvious destiny 55 years ago, Cale has spent over half a century with his finger so perfectly on the pulse of what sounds might push the envelope enough to ruffle the feathers of contemporary pop. After Cale was sacked from The Velvet Underground in 1968 for being too avant garde, he helped sculpt the bedrock of proto-punk even further by producing The Stooges’ eponymous debut record a year later.

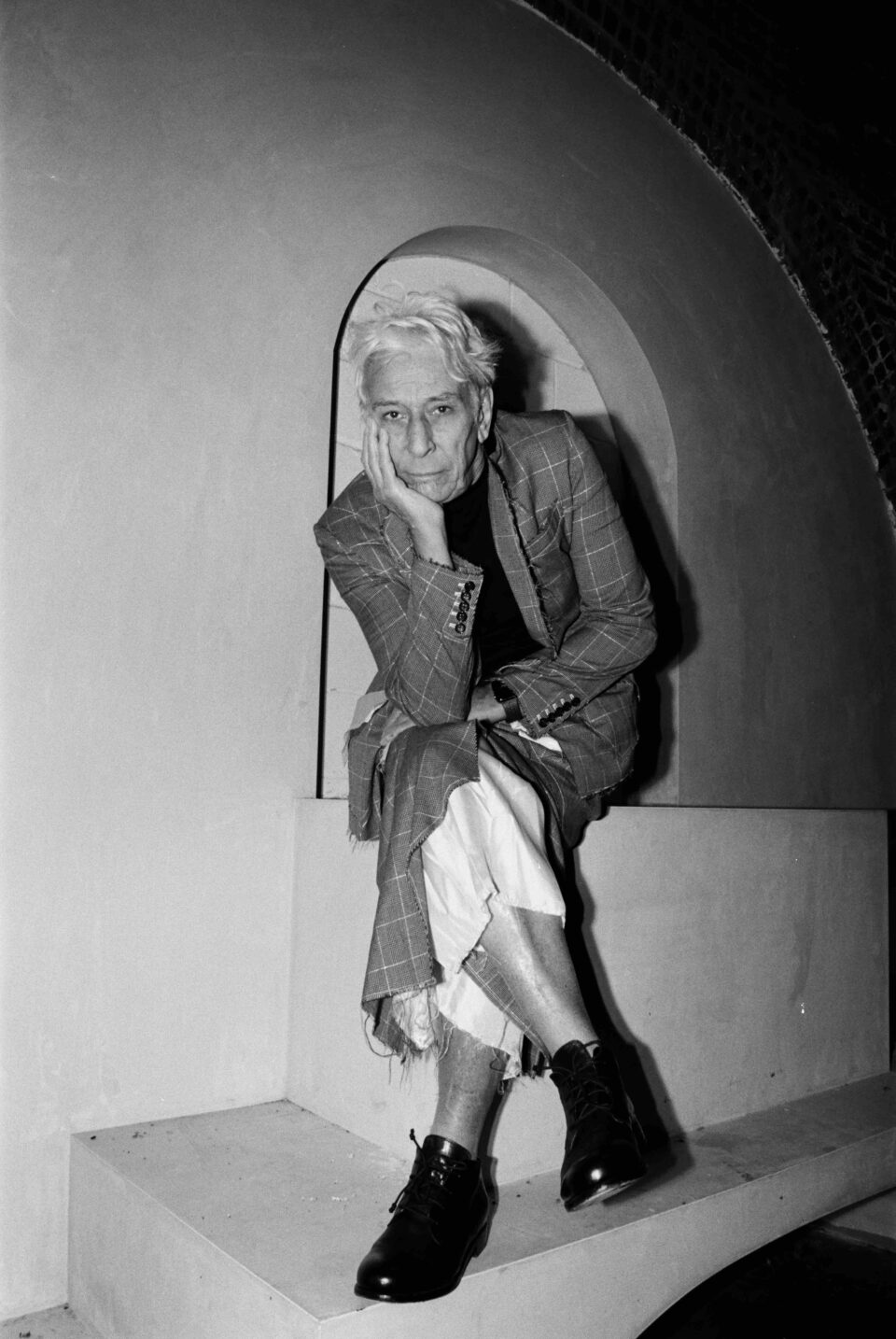

But to really understand Cale’s trajectory as master of aural rebellion, quiet influence, and indescribable, instrumental wizardry, you must go back to his teenage years in the 1950s, when the BBC arrived at his grammar school in Ammanford to cover what the student body was doing. “[They said], ‘Well, what kind of music do you like, and what do you do?’ I lit up and said, ‘Well, I’ve written this piece of music,’” Cale says. The piece he wrote was a toccata in the style of Soviet composer Aram Khachaturian, written on the piano. He had given the score to the producers, but when they returned three weeks later to record his performance, they came with “the van and the tape recorders and all of that,” but not his sheet music. “When I sat down to [play], I had to improvise the rest of the piece,” Cale adds.

A toccata might sound like a grand, fancy composition, and, as Cale notes, it was at the time he got hooked up with the BBC. “When I came out of the recording, it seemed to me that what I was saying to myself was, ‘Come on, it can’t be that easy.’ I was scared into writing the piece, but once I’d done that, I ran the gamut of fear and loathing and so on. Nowadays, I’m in love with improvisation,” he adds.

“I’m looking forward to what I trip over or what I realize about the other collaborator. What is it that I’m going to learn today that I didn’t know yesterday before we met? And it’s always something.”

You can trace some of Cale’s modern legacy back to The Velvet Underground, but his interests were honed before that, while he was living in the Ludlow Apartments on the Lower East Side of Manhattan and working under the tutelage of La Monte Young in his Theatre of Eternal Music. Alongside violinist Tony Conrad, Cale would perform drone and harmonic interval exercises for hours on end.

Young’s use of the musical scale, attempting to play the tonic, fifth, and seventh harmonic concurrently, can be felt on Mercy, as Cale explores the compatibility of improbable pairings, most evident in the anamorphosis of the largely improvised “MARILYN MONROE’S LEGS,” which features sheets of metallic noise atop droning strings. It’s akin to something that might have arisen from the suspended apartment dust after an all-night session between Conrad and Cale, a grand callback to the violist’s mentor and his influence. “[Young’s playing] created excitement of its own kind,” Cale adds. “It’s always in the back of my mind, always to be used.”

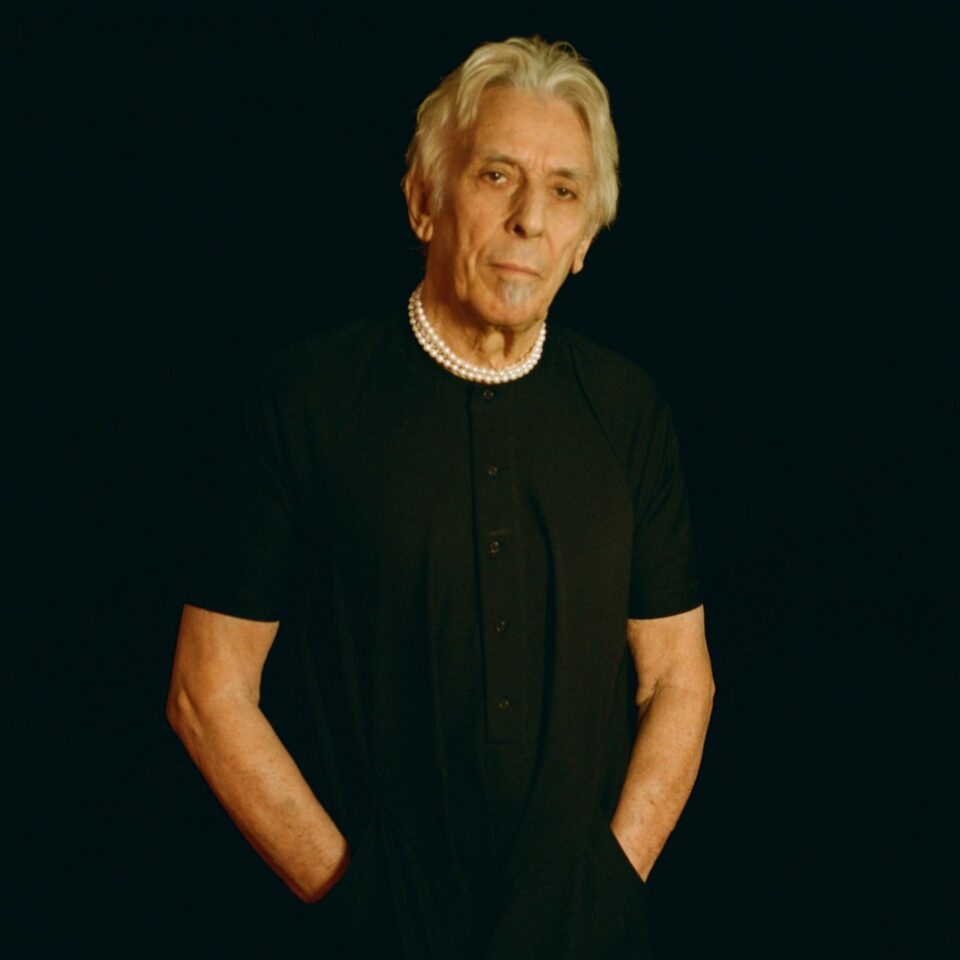

Young’s music project was about the individualistic, but it also sparked an interest in collaboration for Cale, which he has generously brought to Mercy, as he welcomes Animal Collective’s Panda Bear and Avey Tare, Sylvan Esso’s Amelia Meath and Nick Sanborn, Actress, Laurel Halo, Tei Shi, Fat White Family, and Weyes Blood into his world. On Mercy, it’s abundantly clear that Cale, who will turn 81 later this spring, is impassioned by the talents and visions of his peers, many of whom are significantly younger than him. “I generally don’t try and give them a map of where I’m going or where I want them to go,” he says. “It’s a colorful landscape and anything can happen, right? I’m looking forward to what I trip over or what I realize about the other collaborator. What is it that I’m going to learn today that I didn’t know yesterday before we met? And it’s always something.”

Blood Orange’s Dev Hynes plays guitar on “I KNOW YOU’RE HAPPY” and introduced Cale to Tei Shi when they were together in London. “He heard I was looking for a certain kind of background singer,” Cale says. “I wondered if he knew anybody that would have this sweet but really outrageous vocal quality that [Tei Shi] has. It really covers a lot of ground.” The list of collaborators Cale has tapped to fill out the Mercy tracklist is long, a product of one question that stretched across the record: “What kind of vocal do I need here?” To expect Cale to misplace one of his guests’ voices on Mercy would suggest a misunderstanding of just how much perfection the multi-instrumentalist exudes compositionally.

“I was very lucky to have [Weyes Blood] and all of the other people. They all contributed just by their creativity with voices that you don’t really get every day.”

And perhaps that’s how Cale bestowed us with “STORY OF BLOOD,” which begins with a Tom Waits–esque piano that transitions into crunchy static, a breath of atmosphere, and then a chopped-up beat that begs to keep up with the harmonies of Weyes Blood’s Natalie Mering. While recording together, Cale delightedly discovered that Mering was such a malleable force that she could bend her voice to fit the alchemy of the music. “The way I approached all of these songs was I had a concrete plot for how [they] worked out,” he adds. “I broke many of the songs once or twice. I was very lucky to have [Mering] and all of the other people. They all contributed just by their creativity with voices that you don’t really get every day.”

In 1972, Lou Reed and Cale came together to perform at Le Bataclan in Paris. They played a stripped down version of “Heroin,” which you might remember from the credits of Todd Haynes’ 2021 documentary The Velvet Underground. Reed plucked the acoustic guitar better than he ever had before, while Cale sat to his left, bowing his viola less jaggedly than on the studio recording five years prior. Behind them, Nico looked on as Reed and Cale kept time with each other without ever making eye contact. I think about that singular performance often, as, for just a few minutes, the three collaborators held no vendettas against one another and allowed themselves to, again, be transfixed by the music they so beautifully made together.

While Cale was making M:FANS in 2013, Reed passed away from liver disease. Upon the record’s release in 2016, he reflected on how his perspective on storytelling from opposite points of view had changed, seemingly pointing to how sorrow had turned to anger, and sadness to strength, in the wake of his former bandmate and collaborator’s death.

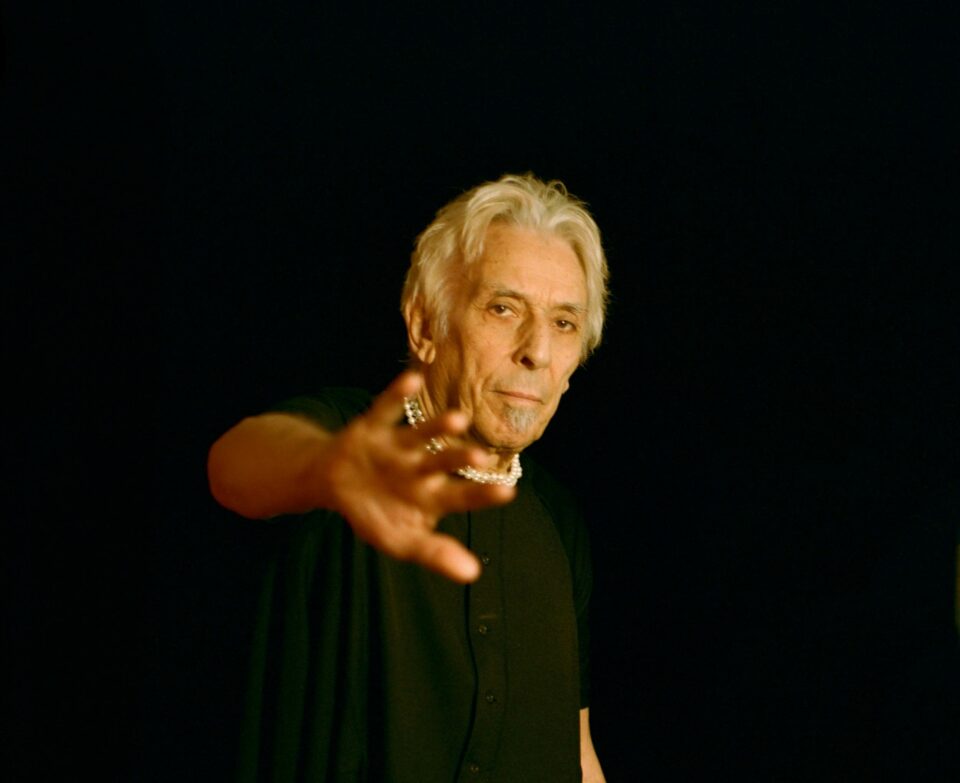

In our conversation, Cale clears the air on what he really meant and notes how he got the idea about opposites from Orson Welles, which allowed him to embrace not just his own ability to let a song become what it demands to be, but the mantra of La Monte Young once more. “It was the way in which [Welles] would approach the collection that went into the work, that he would have opposite ideas working,” he says. “For the song, you’re not attributing any kind of origin to what you’re doing, but you’re ready to listen to what was there already. And this is one of those [La Monte Young] things, that you listen to what is coming at you and you don’t jump at it, but you know it’s there and you listen to what it gives you. Take the values that come at you from other people, try not to get in their way, and let them carry on and finish what you started.”

“In the past three years, I’m listening to Nico’s music and I’m finding something new and different. She, herself, built her own castle.”

The centerpiece of Mercy sees Cale at his most delicate. On “MOONSTRUCK,” he pays tribute to his dear friend and collaborator Nico, who passed away in 1988 from a cerebral hemorrhage. It’s the first time Cale has honored her in song, a moment that he never forced into his discography. When speaking with Cale about Nico, it’s clear that his affection goes far beyond their partnership in music, which included performing on and producing five of her records, from Chelsea Girl in 1967 to Camera Obscura in 1985. “I think nowadays is when I started realizing how much improved her writing was,” he says. “The songs were getting better and better. And don’t ask me why, but a lot of people suddenly realized how there was nothing tricky about how she approached songwriting and the future of music, so I did [‘MOONSTRUCK’] with a lot of gentility and respect.”

On the subject of Nico, one thing that came out of our conversation that I found particularly heartwrenching was this: “In the past three years, I’m listening to Nico’s music and I’m finding something new and different. She, herself, built her own castle.” That remark stood out to me after we discussed the drone exercises he and Tony Conrad did under the guidance of La Monte Young. Young had come from the tonal scale of West Coast jazz and was very strict about what notes he used; on the contrary, Cale wasn’t as formulaic, but he hung onto how he adjusted himself to Young’s playing style. Cale, at the time, shifted from bowing a viola to bowing into a free-string drone. “It was a great noise that we made, just the three strings,” he says. “I filed the bridge of the viola down and it was like having a B-52 coming into your living room.”

“Take the values that come at you from other people, try not to get in their way, and let them carry on and finish what you started.”

Cale and Conrad, along with everyone else in the Theatre of Eternal Music, were also tasked with approaching their position in music—and in life—in different ways and addressing the question of, “How do you get out from this hole that you’re in?” Cale’s response now registers some 60 years of learning, genre-breaking, and collaboration, and it succinctly emphasizes the singular truth of how deftly underrated his influence on three generations of music has become: “You suddenly realize it’s not a hole anymore. It’s just living your life and building your castles.”

January 30 marks the 55th anniversary of White Light/White Heat, the last Velvet Underground album Cale played on. The band recorded it in 12 days, leaning heavily on the improvisational techniques they’d employed on-stage while tinkering with complex levels of distortion. The song “The Gift,” sung by Cale, was a feat in stereo engineering: The lyrics, culled from a short story Lou Reed had written in college, are delivered like a monologue by Cale and play through the left speaker while the dynamic rock instrumental, laced with feedback and untuned guitars, pierce through the right. If The Velvet Underground & Nico grandfathered proto-punk, then White Light/White Heat stapled it to a rocket and shot it at the sun.

Two of the four players on that record have since passed on, leaving Cale here on Earth, pondering a new sense of mortality catalyzed by an epidemic of illness and political extremism. But in the darkness, a clarity awakens: “I hear you now,” he beckons on Mercy, his castle built from the noise he’s broken, reshaped, and renamed over and over. FL