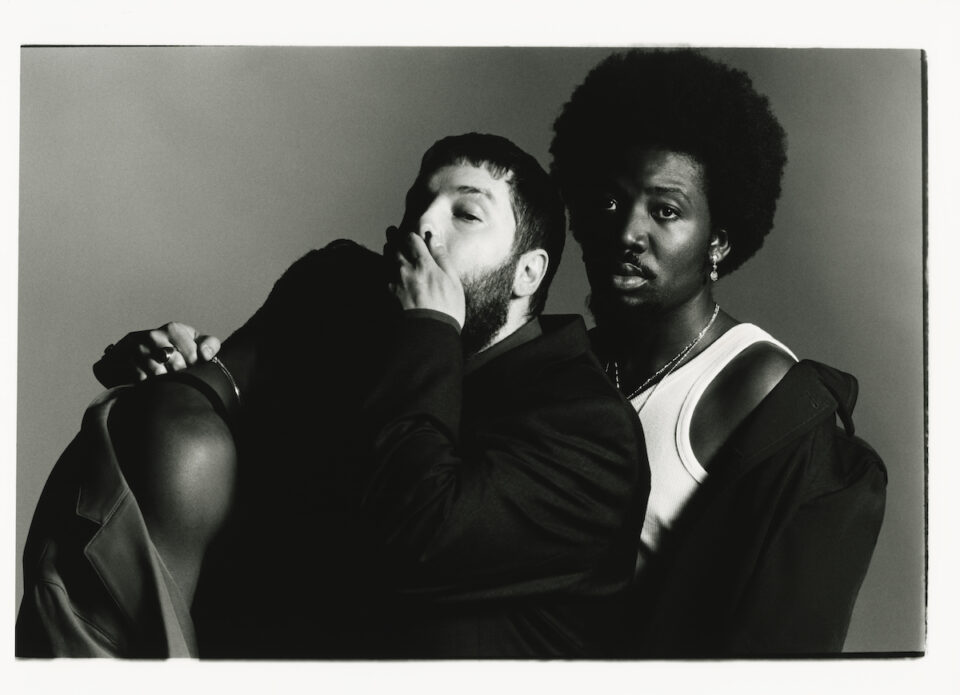

In going back to the basics, Alloysious Massaquoi has an energy as infectious as his band’s music. He brings a conversational liveliness to our interview, like he’s nesting the punch of Young Fathers’ short and sweet songs in each passionate response.

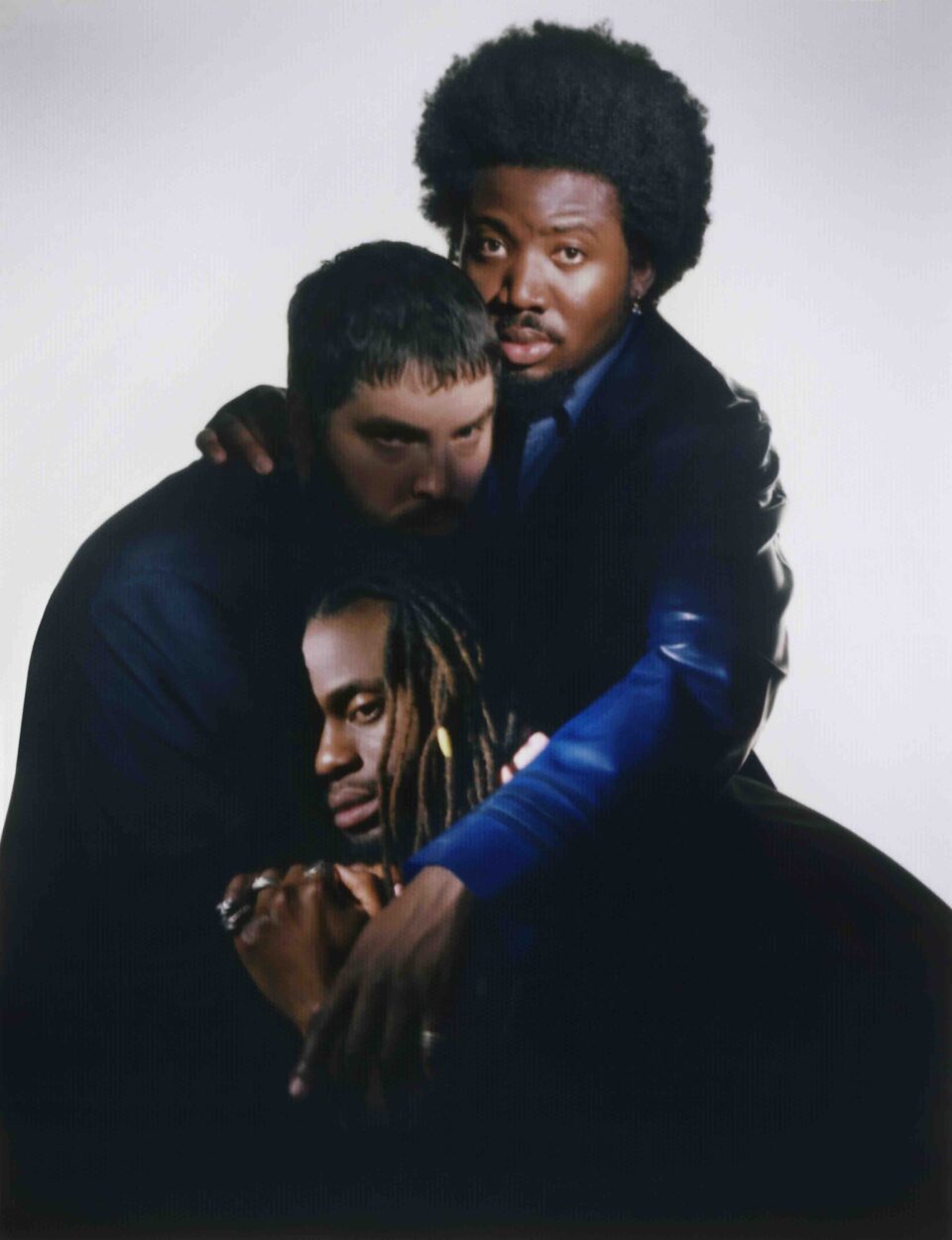

In their time together, the genre-breaking trio of Massaquoi, Kayus Bankole, and Graham “G” Hastings broke through with 2014’s Mercury Prize–winning Dead, but kept steadfastly refusing to rehash what put them on the map, choosing instead to reinvent their sound at every turn. Their latest record Heavy Heavy is no different, while still feeling entirely new. Here, Young Fathers returned to their earliest form: paring the personnel down to just the trio in a basement, leaning into the rawer elements of their sound—a hard left turn from the studio sessions of their previous release, Cocoa Sugar.

Massaquoi’s words about the album are playful yet considered, measured but sincere. At times, he breaks into singing lyrics that best illustrate his points, whether they be ones Young Fathers penned or the soul and reggae classics he references. Near the release of Heavy Heavy, we discuss with Massaquoi how the record breaks new ground for Young Fathers, the songwriting freedoms of recapturing the band’s youth, and the humanity at the core of the album.

The choice to scale back to more of a DIY approach is really fascinating at this point in your career. What pushed you to shift back to that now?

I think it was just time apart. We took a break after 10 years of touring and recording. [Graham] had a baby, Kayus was traveling to Africa, and I was just at home, enjoying the pros and cons of the mundane life. And I think that helped get us into a space where we were like, “Well, things are changing—in the world and within the band—let’s get together and start this process again.” It just made sense. When things just go ’round, we end up back to how it used to be when we were kids.

How did the freedom in going back to these origins help that sound?

I think it stems from everyone having short attention spans [laughs]. There’s a lot of range in what we do, because we all like different stuff, but I think what keeps it together is that we try to identify with the feeling of the song more than anything else. With that, it can splinter off in different conversations and in different sounds. It’s almost like a glorious mess—we’ll find a way [to make it] work. We always say we don’t want to do the same thing twice. We always want to push ourselves, and there’s an excitement there [about] what’s around the corner. There’s quite a few surprises on this record where you think, “Oh shit, we didn’t think we had this in us.” But that’s what you want. You’re trying to feed that beast to create these things.

“We always say we don’t want to do the same thing twice. We always want to push ourselves, and there’s an excitement there about what’s around the corner.”

I’m especially compelled about how that factors into your vocal presences on the record. It’ll almost be like one of you is rushing in when another one is still on a line. Do you feel like that’s part of your spontaneity as a group?

Yeah, I mean, we’re all trying to cram in as many ideas as possible. But again, it’s the short attention span [thing]. You have so much that you want to say. We encourage that sort of thing. When it started when we were 14, we’d literally be recording in Graham’s bedroom, in the cupboard, with the karaoke machine wrapped around the cupboard door, and we’d all be really close to each other. You go back to what you know and what serves you—what’s best for you and what feels the most natural.

I read that you record with mics on at all times to make sure you don’t miss anything. How does the idea of a song form with that?

There’s nothing premeditated except the time and location [of recording]. Everything’s left on because spontaneity is our strongest suit, our calling card. You set things up for that to happen, and then someone says something, or someone grunts or screams or has one line they keep saying—and that’s the essence of the track. “OK, let’s build from this point.” That’s how we made the record—it had this communal aspect all the way through, and those 10 songs had the most togetherness and community.

With those essences you’re talking about, your hooks will often be just a single word or short phrase repeating. What power does that simplicity of repetition hold for you?

Sometimes you just need to say the simplest thing and that’s what people respond to. Like James Brown’s “Please Please Please”—there’s so much power in just saying the same thing over and over, and it sounds different the more you say it and the more the music crescendos and builds. Sometimes one or two lines is all the song needs, because it gets to the essence of whatever you’re trying to say.

“We were the kind of guys who would turn up with three-minute pop songs and dance moves at rap battles—we didn’t want to subscribe to this idea that you have to be hard or tough, or [the idea that] it’s a competition of who’s been oppressed the most.”

I’ve always been fascinated by the role that percussion plays in Young Fathers. It can completely change the energy of a track, especially when you initially withhold it. Where does that come into the process for you?

It’s important for us to put in the percussive stuff when it’s needed, when you’re trying to build up to a certain point. Then you take it out suddenly, and then it comes back in on an offbeat. Or if you want to surprise people, you do something right at the start and they go, “Whoa, I wasn’t expecting that.” And then you maybe break it down as a song continues, or build it up and get this release toward the end. That’s usually how songs work, but it’s how you get to that point that’s the most interesting part of the process.

“Shoot Me Down” has that sense of surprise right at the start with this cut-up vocal sampling. How did that get built?

I think we’re intentional about it being a build right at the start, with that claustrophobia. And then boom, that vocal comes through and just carries it. It’s the first release. It’s all [in] the dynamics, and I think that track is really dynamic. The song went completely wherever, and that’s what we want. We set it up in the best way, and it ended up being something completely different. That’s what we’re addicted to, that surprise.

In a similar vein, there’s “Ululation” right after that. I read you struggled with that track before the vocal part brought it together—what made it initially difficult? And what appeals to you about its place on the record?

We put a couple ideas down and some vocals, but it just didn’t feel right. I have this [expression about a song] where it feels like you can swim in it. You can really get into the track and pop your head up, then go back in. It just wasn’t that feeling. Then Taps [Tapiwa Mambo] came in and did what she did, and it instantly clicked.

“Ululation” felt like a transition in the tracklist, something to take you from one part to the next. Prior to that, we thought the record would be better with seven songs, because it felt so intense up to that point. It felt like something was missing. What “Ululation” did was reset the palate. It allows you to breathe for a moment, go through whatever you need to go through. It felt like a ceremony of some sort—you come out the other end and your perspective has changed.

“Music can be whatever you want it to be—we embody that. We try our damnedest to keep that up and be consistent, to find these ways of being a fucking human.”

Then there’s “Be Your Lady” closing that journey, while taking a really fascinating journey of its own. You’ve talked elsewhere about subverting masculinity and I was wondering if that was something you had in mind writing that.

Kayus, the other day, said it was the most radical track for him because of all the different transitions it goes through. We always love that sort of wave goodbye right at the end of a record. To subvert [expectations] is just to be you in your truest form and express that, and be unapologetic and intentional about that. As soon as you do that, though, you stick out like a sore thumb. A lot of people aren’t ready to do that, for good reason—there’s punishment for stepping outside of those boxes. But as long as you’re staying true to you, there’s strength in vulnerability.

People think that’s a weakness, but to me, it’s a strength. We were the kind of guys who would turn up with three-minute pop songs and dance moves at rap battles—we didn’t want to [subscribe] to this idea that you have to be hard or tough, or [the idea that] it’s a competition of who’s been oppressed the most. So we just went in with that [aim] of being yourself, and [doing] what felt right and natural to who we are. A lot of those attributes are marginalized and othered, but we just go, “This is what we want to do.” Music can be whatever you want it to be—we embody that. We try our damnedest to keep that up and be consistent, to find these ways of being a fucking human.

The title Heavy Heavy gets into all these conceptual complications too. It can refer to anything from the record’s sound to its larger global context. What power does the ambiguity of that title hold for you?

I think it allows the record to live a lot longer. What I find with great art is that you always want to go back to it. In reggae songs, someone can sing the sweetest thing ever, but the lyrics are dark. That duality is happening all at once. If the record was just called Heavy, that would give a completely different connotation. Heavy Heavy is playful. I think that speaks to the creativity and the range of the music. It also leaves an element of surprise, because you read it and go, “What does that mean?” It asks those questions and brings intrigue. Ultimately, in my head, it’s undeniably steeped in humanity. It’s a full human being with faults. That’s the journey: you go through all those things. And then you press repeat.

And there’s the power of repetition again right in the title.

That’s it. We’ve always been that kind of band where you just want to press repeat, because we like stuff short and sweet. With great stuff, you go back and hear something different, something you didn’t hear before. You want to make something where someone will go, “That’s the one that changed things for me.” FL