“Weird Al” Yankovic has always relished satirizing pop hits with clever lyrical takes, making popular songs fresh again with his mirthful twists. He originally exploded in popularity in the 1980s, but his fan base has remained steadfast throughout his career. His last album, 2014’s Mandatory Fun, became the first #1 album of his 40-year recording career, and it also won him his fourth GRAMMY, this time for Best Comedy Album (he’s won another since). Al has been getting renewed attention recently because of the hilarious Weird: The Al Yankovic Story, a fake biopic starring a buff Daniel Radcliffe as the alternate-universe Al who truly lives a decadent rock star life.

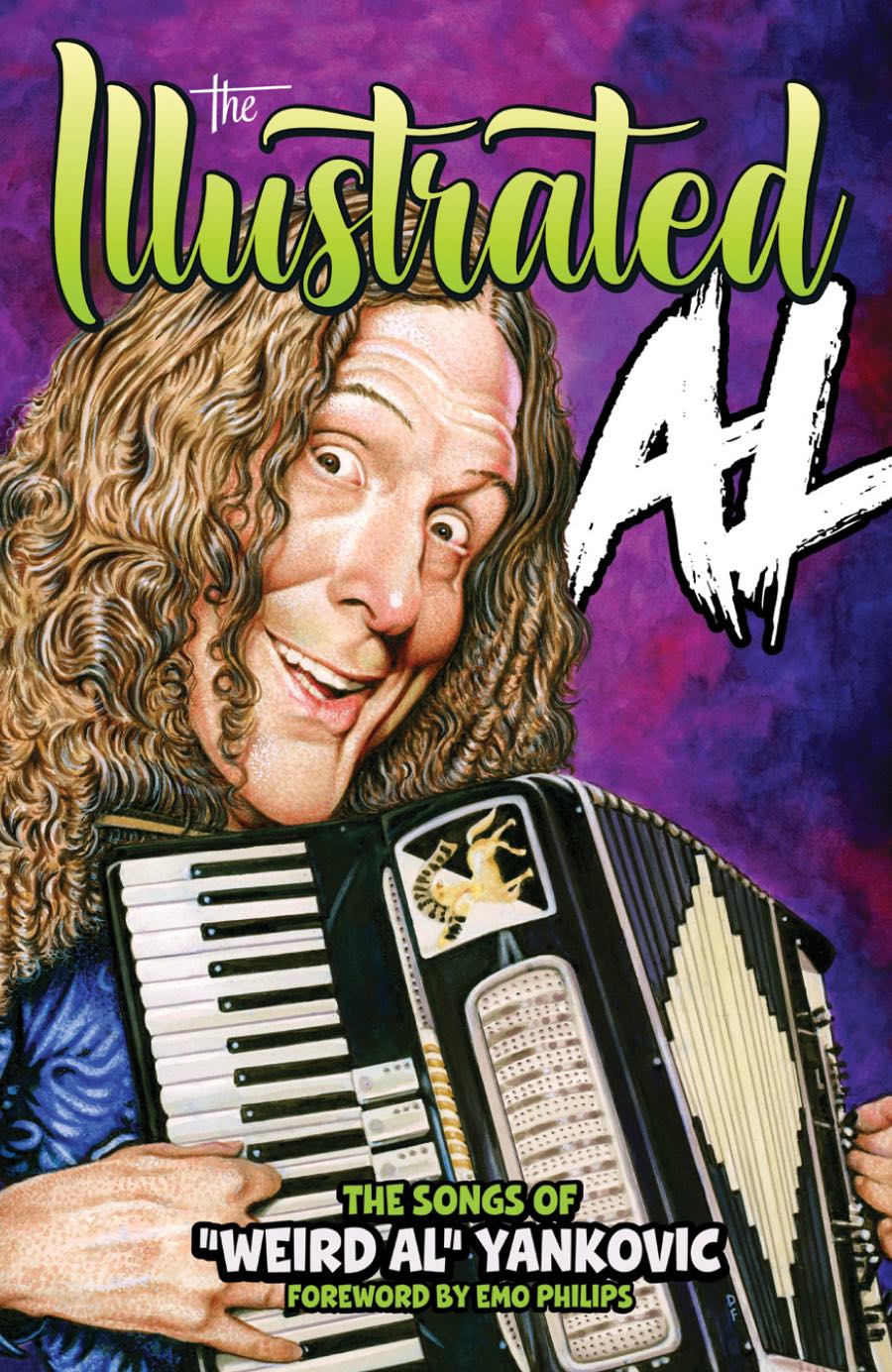

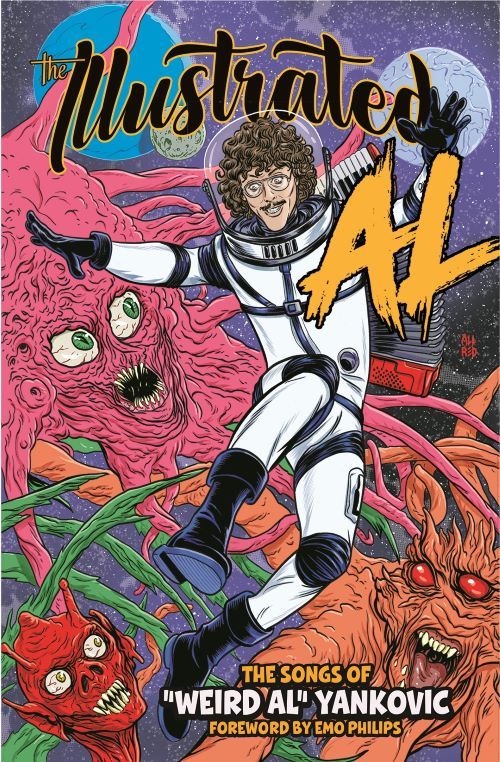

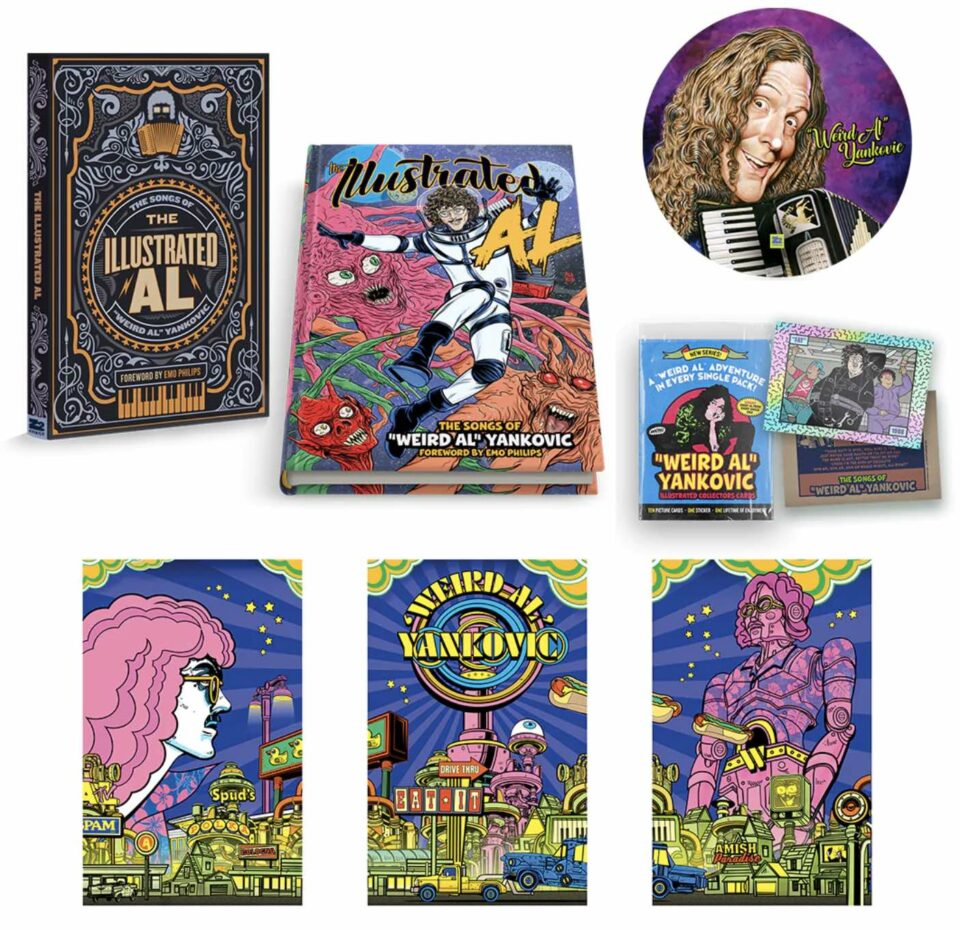

The famed musical comedian has also recently been involved with the Z2 Comics graphic novel anthology The Illustrated Al, inspired by his oeuvre. For this comic collection, Yankovic picked artists he admired to interpret 28 songs in their own special way. It’s quite diverse in terms of artistic styles and interpretations, which range from zany to unsettling. His biggest hits get one to two page spreads, but other tunes receive greater exploration. For starters, we get Ruben Bolling’s Sunday-funnies-gone-awry version of “You Don’t Love Me Anymore,” Brent Engstrom’s trippy take on “Mr. Popeil,” and Bill Plympton’s bloody rendering of “One More Minute.”

In our conversation, Yankovic speaks about the realization of the project, how he felt about the different interpretations, and his love for MAD magazine.

With this collection you get to be a little more off the cuff, even a bit gory. Did you feel like you had more creative freedom than you would in a Weird Al video?

Well, I didn’t give a lot of direction—almost zero direction. I chose the artists, and obviously the lyrics are my own. But other than that I gave free rein. The only time I gave them a note was when they got the lyrics wrong.

In the credits in the front of the book it says “lyrics and stories.” Did you write any of the story scenarios for these?

No, they did absolutely their own interpretation. So if there’s any story to be had, that’s purely from the artist. A lot of times, [Z2] do these books with musicians and artists where the illustrators do, in fact, create a story based on the lyrics. That didn’t interest me so much because many of my songs tell the story already, and the ones that don’t, I’d rather them not create something that I hadn’t thought of already. So basically I said, “I’d love to do this book, can you please just have it be the lyrics and have the artists do their own interpretation of that?” Also, it’s cool that most of these songs are originals which never got a music video. I was excited about the opportunity to have somebody attaching visuals to these lyrics.

“It’s cool that most of these songs are originals which never got a music video. I was excited about the opportunity to have somebody attaching visuals to these lyrics.”

I noticed that all the mainstream hits like “Fat” and “Amish Paradise” get one or two pages, while other fan favorites and recent songs get the bigger spreads.

Yeah, because the big hits already have their big music videos to go along with them. I was trying to shine a light on some of the songs that don’t get that much attention. Much like the tour that I’m currently on.

You were guest editor on MAD several years ago, and they said you actually were a guest editor—you didn’t just slap your name on it, you actually edited it. Was that good boot camp for this gig?

In a way, sure. That was an amazing thing because growing up I was obsessed with MAD magazine. That’s one of those things I wish I could go back and tell my 12-year-old self—that one day I would be on the cover of MAD, and that I would be editing the magazine. But yeah, I went through and I fixed their typos, and I made a lot of creative decisions. It was a great opportunity to work with some of my heroes.

There’s always been a racy side to Weird Al, though you never push it too far. Have you ever worried about that, looking back at your own stuff, going, “Oh, I shouldn’t have said that”?

Of course. There’s always stuff that you can be embarrassed by. [On] a lot of my early albums there are amateurish bits that I’ve done. There are some words that I used early in my career, and even more recently, that I’m not happy that I used because language changes and things that weren’t offensive in the ’80s or ’90s are offensive now. Language is fluid, and you just learn and do better.

The spreads for “Mr. Popeil,” “My Own Eyes,” and “Jackson Park Express” have that counterculture psychedelic look reminiscent of indie comics from the ’60s. Were you into Robert Crumb and the like back then?

Yeah, I like Robert Crumb. I made sure that we hired a lot of my favorite indie cartoonists from alternative papers and things like that. Outside of MAD magazine, I can’t say that I was a voracious comic book reader, but I always appreciated the art form. I always felt a certain kinship with those people.

“That’s one of those things I wish I could go back and tell my 12-year-old self—that one day I would be on the cover of MAD, and that I would be editing the magazine.”

Were you a Marvel or DC guy as well?

I liked those comic books. I wasn’t somebody that subscribed to Marvel or DC. It was purely the comedy books—MAD, sometimes Cracked if I couldn’t wait for MAD [laughs]. That was where my interests were. But if there was a copy around, I’d pick it up and read it.

Have you been amazed at how comic book culture has blown up in the 21st century?

It’s made it cool to be a nerd now. I think somewhere about 15 years ago when “White & Nerdy” came out, I really felt a paradigm shift where instead of nerds being the people that got beat up in P.E., they were the people that you aspired [to be]. People are bragging about their nerd cred, which is something you never heard about when I was growing up. I think comic book culture, the Marvel movies, all that, shone a light on the fact that there are a lot of nerds out there, and there are a lot of cool nerds out there. Nerds make some of the coolest things.

“Good Old Days” is a darkly comedic ballad, but the comic book version gets into a disturbingly poignant apocalyptic sci-fi scenario. How did you react when you first saw that?

It was an interesting take, an interesting story. That was Jeff McClelland and Jeff McComsey. I really enjoyed that. It was something that obviously I didn’t think of, but it was a way to tell the story in a very interesting way, which I appreciated.

Have any of the stories in this anthology made you reconsider the point-of-view of the songs?

[Laughs.] That’s hard to answer. I don’t know if they change the song’s meaning in my own mind. I just appreciated their interpretation of it. That’s the thing with these songs—before visuals are attached, people can make up their own movie in their heads. So it was interesting to see what their movie was.

“When ‘White & Nerdy’ came out, I really felt a paradigm shift where instead of nerds being the people that got beat up in P.E., they were the people that you aspired to be.”

In “Trigger Happy,” which deals with gun culture in America, there’s one panel with the lyric, “What have you got to lose?” And there’s a guy holding up a gun to his lips who looks like Kurt Cobain. Was that intentional?

You’d have to ask the artist. I mean, that’s what I got from it. I thought that it was dark and very edgy, but I thought, we’re living in edgy times. I certainly didn’t veto that. I was like, “Alright, go there, fine.”

Are there any artists that you wanted to get for this that you couldn’t?

I’m trying to think if anybody turned us down. I guess a few people did [just because of scheduling]. But we got pretty much everybody that we went after. People were excited to work on this. I had my wish list. [People who said no said] “I wish I could.”

Which of these stories affected you the most, out of all the interpretations of your songs in this collection?

Gosh, maybe the “Trigger Happy” one, just because that was the darkest and the most socially relevant. They all had an effect on me, but that one was pretty, pretty deep. FL