At this year’s GRAMMYs, the first-ever Song for Social Change special merit award was given to the Farsi-language song “Baraye.” The work of 25-year-old Iranian musician Shervin Hajipour, the lyrics to “Baraye” (which translates to “For”) are taken from posts by Iranians in reaction to the brutal murder of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old woman who was arrested and beaten to death by the Islamic Republic of Iran’s morality police for her insufficient head covering. She died on September 16, 2022, three days after her arrest.

“Baraye” has become the global anthem for protests that were ignited by Amini’s death, against the oppressive and dictatorial Islamic regime that has ruled Iran for 44 years. Over five months later, this unrest is considered a revolution with the resistance against the regime still going strong. Where there is Iranian diaspora, there are regular protests—particularly in Southern California, home to the largest concentration of Iranians outside of their home country.

For Iranians across the globe, that moment at the GRAMMYs was seismic. For us North America–based Gen Xers who remember Iran prior to the Islamic Revolution of 1979, the award is redemptive. We were in the line of fire when the Islamic government held Americans hostage for 444 days. We were the ones who rebranded ourselves as Persian, the ones who can’t quite shake that Farsi accent, and the ones who had to justify our family’s immigration struggles.

For Iranian millennials, who only know life under the Islamic regime, the award is a source of pride and motivation to keep resisting. For Iran’s Gen Z, who are the instigators of the current Iranian Revolution, the ones who have had enough of irrational and inconsistent laws, the ones who can only see a future if there is no Islamic Republic, the ones who are risking harsh prison sentences accompanied by rape and torture and violent deaths for freedom, the award is a symbol of their sacrifices.

The slogans heard at protests are cathartic. They’re led by “woman, life, freedom,” followed by “man, homeland, prosperity,” words heard in “Baraye.” This liberating feeling is the opposite of how protests used to make me feel. When I was nine years old and temporarily living in Iran, my safe and carefree existence—which revolved around my American school’s library, Western music, and summer trips to Europe and the States—was shattered overnight because of the 1979 Islamic Revolution protests.

HOW IT USED TO BE

Later-generation Iranians have only heard stories of pre-revolution Iran, and it’s captured their imaginations. Electronic musician Nostalgix was born in the Iranian capital of Tehran post-revolution and moved to Canada as a child. “Every photo I’ve seen of my family pre-revolution has been full of light, smiles, and life,” she says. “People were allowed to express themselves. Everyone was free to live a life full of love.”

“Everything was beautiful, lively and vibrant—it seems like a fairytale,” says traditional Iranian singer Hengameh, who recently collaborated with multicultural GRAMMY-winning group Opium Moon on the song “Woman Life Freedom,” inspired by current events in Iran.

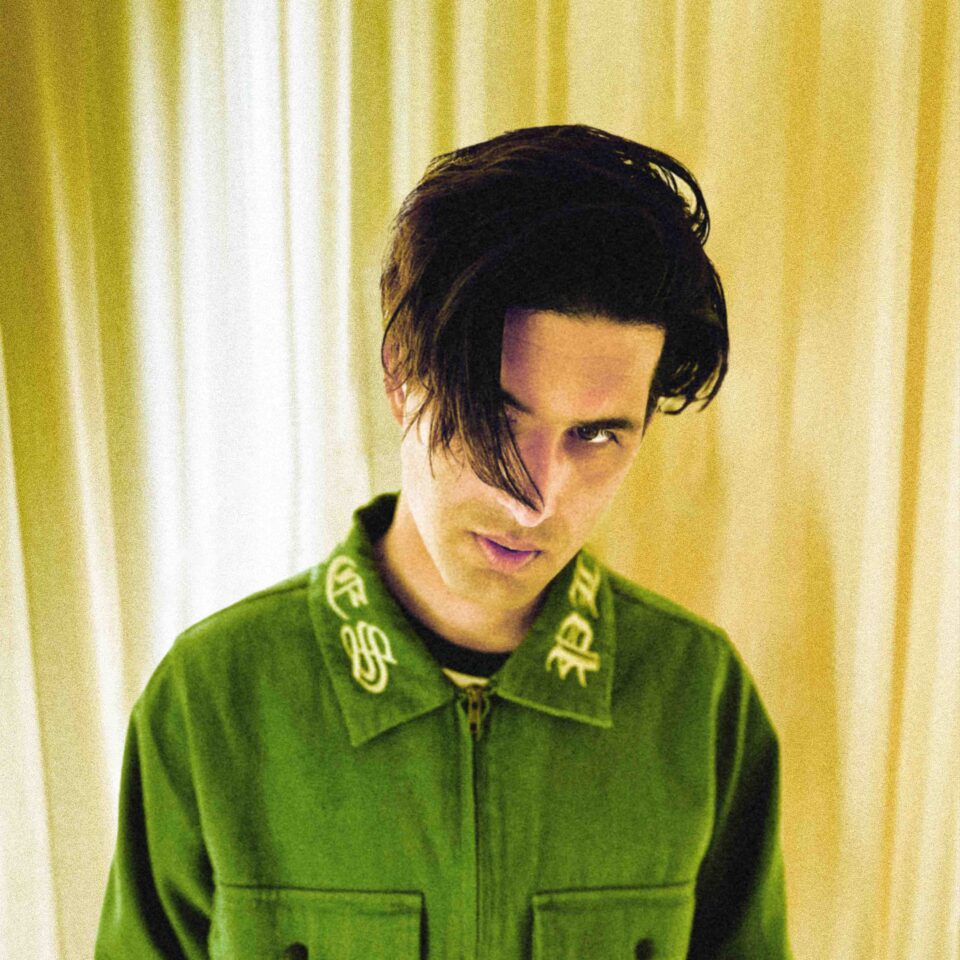

Nostalgix

“Every photo I’ve seen of my family pre-revolution has been full of light, smiles, and life... Everyone was free to live a life full of love.” — Nostalgix

Rudimental’s Amir Amor was also born in Tehran after the revolution and lived there until he was seven. He heard many stories from his parents about “how prosperous life was becoming prior to the revolution, especially for women.” Says Amor, “I was exposed to pre-revolution music in the house, like Googoosh and Kourosh Yaghmaei, which helped me imagine what life was like back then.”

During a trip to Iran in the ’70s, in his formative years Supreme Beings of Leisure’s Ramin Sakurai had some life-changing musical discoveries. Among these was a cassette soundtrack of Bruce Lee’s Enter the Dragon by Lalo Schifrin. “I wore it out,” Sakurai remembers. “I still know every single note of that score. My mother and others listened to Googoosh and other Iranian pop music. You could definitely hear the Western influences in the music at the time, especially disco, some rock, and even funk.”

Amir Amor

Mid-20th century Iran was a progressive place with arts of all kinds being celebrated, music in particular. Still, there was a huge divide between social classes and restriction of political thought, speech, and expression—although nothing like the oppression that has been in place since 1979.

AFTER THE ISLAMIC REVOLUTION

After the Islamic Revolution, all things Western were forbidden, particularly music. Gone were radio stations, discos, dancing of any kind, public gatherings with entertainment. Also gone were movie theaters and television stations. The programming became strictly religious content with a decidedly punitive bent. Iran went behind a dark curtain, not unlike the hijab, or covering of head and body that became compulsory for all women.

“I went from being able to sing publicly to not even being able to sing privately at gatherings with groups of friends,” recalls Hengameh. “I didn’t realize just how much our lives had changed until one night when a group of us were gathered at a friend’s home. The evening was filled with music, dancing, and laughter. I was encouraged to sing a few songs. Next thing I remember is police raiding the home and arresting every single one of us.”

“The evening was filled with music, dancing, and laughter. I was encouraged to sing a few songs. Next thing I remember is police raiding the home and arresting every single one of us.” — Hengameh

For me, the American school I attended was shut down and its extensive facilities taken over by the Islamic government and turned into an elaborate revolutionary guard headquarters. I was at a loose end academically and at a confusing juncture with my identity. I was born in the US when my parents were living here as part of my father’s job. I spoke English as my first language. My Farsi was deplorable, my reading and writing of the language at kindergarten level.

My parents chose to remain in Iran, aiming to legally immigrate to the US when I was entering college. In the meantime, by eighth grade, I was ensconced in public school and a five-year nightmare of fear, berating, and humiliation by school officials began. This was the case for all my classmates, but I was made a particular example of because I was American. I was stifled and oppressed, with high school graduation marking the light at the end of a very dark tunnel.

Nostalgix visited Iran as a teenager and experienced the oppression firsthand. “Self-expression was completely non-existent,” she recalls “I felt like I had to constantly dull myself down to fit in with the image of how a woman should behave. I remember going to the beach and quickly learning that it’s illegal for women to be swimming without being fully covered up. I had to get into the water in my hijab.”

“For me, there were a lot of battles with identity... As a kid, I found myself embarrassed, ashamed, and confused about my heritage.” — Chain Gang of 1974

Composer and santoor player Hamid Saeidi of Opium Moon recalls horrific stories about encounters with the Republic’s revolutionary guard—or IRGC—who were “hiding crushed pieces of glass in the middle of napkins and then handing them to ladies and demanding that they remove their lipstick with the napkins immediately.”

Kamtin Mohager of Chain Gang of 1974 and Heavenward was born and raised in the US. His family is of the Bahá’í Faith, and they had a difficult time post-revolution. Says Mohager, “It was well-known amongst our community that after the Shah was overthrown, Bahá'ís were not allowed simple human civil rights. I heard stories of businesses being taken over by the regime, along with access to education being denied due to their religious beliefs.”

Mohager’s experience post-revolution has both overlaps and divergences from his fellow musicians in the Iranian diaspora. “For me, there were a lot of battles with identity,” he says. “I moved to the Big Island of Hawaii when I was three years old and spent my entire childhood there. At the age of 13, we relocated to the southern suburbs of Denver, which is primarily white. As a kid, I found myself embarrassed, ashamed, and confused about my heritage.

“As I’ve gotten older,” he continues, “I’ve done my best to educate myself more on what the Iranian people have been through and to stand by them as they continue to be persecuted by their own government. My views may be different from a person who is Moslem and lives in Iran because I did not grow up in an Islamic household. But we’re now seeing these differences are being put aside, and the people, regardless of their age, sex, or religious beliefs, are coming together to fight for unity.”

CURRENT UNREST

The current uprisings are not an isolated occurrence. There were revolts in 2009, 2011/2012, 2016/2017, and 2019/2020. Each revolt—which carried on for months—was sparked by dissatisfaction with the government. In turn, each protest had its share of imprisonments, killings, and inventive brutalization of Iranian citizens by the government, which covered its human rights violations by shutting down the internet in the country.

The present moment’s protests-turned-revolution are the most visible on the international stage. They’re led by a generation who grew up watching the free world outside Iran on their devices. In their late teens and 20s, this group is on the cusp of their adult life and is seeing no future within Iran. Educated or not, with the escalating rate of inflation in the country and lack of employment opportunities that would pay enough to support a family or buy a home, it’s a situation equivalent to no life at all. Despite two prior generations suppressed by fear, Iran’s Zoomers are putting themselves on the frontlines of this revolution, knowing that they could be maimed, imprisoned, or killed.

“The economy has been in absolute shambles. When you take away everything from people, they have nothing to lose.” — Kittens

“The people are exhausted,” says Iranian-American DJ/producer and podcaster Kittens. “The economy has been in absolute shambles. When you take away everything from people, they have nothing to lose. There have been multiple uprisings since the regime took over, but now it’s the perfect storm. People have had it, and we have social media to connect and share like never before. They’ve made sure the whole world knows.”

Nostalgix concurs: “Without platforms like TikTok and Instagram, the world would have no idea what’s going on in Iran and how the people are being treated. Gen Z is at the forefront, risking their lives to speak out. Without the power of social media, the people of Iran would be silenced.”

IRANIAN ARTISTS TARGETED

The Iranian voices that have been heard the loudest are those of the country’s artists, musical and otherwise—for which the Islamic regime has made them pay dearly. Hajipour was arrested the day after posting “Baraye” online. He was released on bail and is awaiting trial on nebulous charges.

After Hajipour, dissident rapper Toomaj Salehi is perhaps the most notable artist behind bars. Salehi has been in solitary confinement for over 120 days. One of his eyes is close to losing sight due to severe beatings he received when he was first arrested. His charge is “enmity against God.” This is a hazy “crime” the clerics ascribe to anyone who goes against their hardline government, and its punishment is execution. This is not Salehi’s first arrest. He’s prolific, and his rhymes speak of the Islamic regime’s injustices. He delivers truths with such clever precision—he was never going to fly under anyone’s radar. To quote Sakurai, “Music is beautifully dangerous, the ultimate weapon of truth.”

“To think that Iran—a place that is so rich in talent, culture, and art—has become a place where artists can be arbitrarily detained, jailed, and put to death is something I still have a difficult time processing.” — Hengameh

Also under arrest is rapper Saman Yasin Seydi and numerous other creatives, professionals, and innocent, peaceful protesters who all face the possibility of the death penalty. Says Hengameh, “To think that Iran—a place that is so rich in talent, culture, and art—has become a place where artists can be arbitrarily detained, jailed, and put to death is something I still have a difficult time processing.”

Working as an artist in Iran for 13 post-Islamic regime years, Saeidi has direct experience with the fear attached to expressing yourself. “I feel the pressure in my heart,” he says. “The fear for your life, the life of your loved ones, losing everything overnight, of torture and the ultimate sentence of a rope around my neck—I remember it all. I salute the brave artists who have stayed in Iran and are fighting with their art, their talent, and their voice.”

“Throughout history, artists have always been an integral part of political and social resistance,” Kittens points out. “It’s an important role that comes with risk. But when you have a platform to express feelings that millions of people have, you have the ability to support the needed change. Everyone in Iran knows the current regime isn’t scared to make an example out of people who are leading the revolution in any way. Artists who are stepping out know what comes with that.”

NON-IRANIAN MUSIC ALLIES

There are a small number of non-Iranian musicians who have been vocal about the dire situation in Iran. Among the most prominent are Coldplay, Yungblud, and Dua Lipa, who have all used their massive platforms to bring attention to what’s been happening in the country and to its people. Additionally, Bonobo and RÜFÜS DU SOL wore #FREEIRAN pins on the GRAMMYs red carpet. These pins were furnished by United Iranian Americans, an organization aiming to bridge the gap in knowledge between Iranians and non-Iranians, who are the conduit between the Recording Academy and the sequestered Hajipour.

Most outspoken and proactive has been Taylor Hanson, who started a nonprofit foundation called For Women Life Freedom. Hanson is using his star power to create a “We Are the World,” so to speak, for Iran, based on a new chorus arrangement of “Baraye” called “Baraye – For Women Life Freedom,” which Saeidi is co-producing.

Freedom is at the core of the Iran Revolution. It’s the goal for which all the lives that have been lost and those who are being detained and tortured are working toward. It’s the overarching fundamental human right that eradicates oppression and persecution, while encompassing equality, safety, and peace.

As Amor says, “It’s vital that we keep speaking about it to keep it in the mainstream psyche.” FL