Few bands have had as unusual a career trajectory as The Zombies. After forming in the early 1960s as teenagers, the English group achieved international smashes with their first two singles—“She’s Not There” and “Tell Her No,” both released in 1964—then spent the next three years releasing forward-thinking, keyboard-driven music to diminishing commercial returns before splitting up at the end of 1967.

Their final LP, the Abbey Road–recorded Odessey and Oracle, failed to chart upon its initial release in 1968, but the album’s closing track “Time of the Season” went on to become a hit in the US and remains an iconic anthem of the hippie era. Odessey and Oracle now regularly turns up on “Best Albums of All Time” lists, and has been hailed as a masterpiece by musicians ranging from Paul Weller and Tom Petty to Opeth’s Mikael Åkerfeldt and Susanna Hoffs of The Bangles, the latter of whom inducted The Zombies into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2019.

All of which would make for a fascinating story in and of itself (one which will presumably constitute much of Robert Schwartzman’s Hung Up on a Dream: The Zombies Documentary) if The Zombies’ keyboardist/songwriter Rod Argent and lead vocalist Colin Blunstone hadn’t started working together again three decades after the band’s initial split. Since then, the revived Zombies have toured the world numerous times and released five albums—the latest being this past March’s remarkably vital Different Game.

Recorded primarily at Argent’s home studio, Different Game—which features the current lineup rounded out by drummer Steve Rodford, guitarist Tom Toomey, and new bassist Søren Koch—is a fitting addition to the band’s recorded legacy. Songs like “Dropped Reeling & Stupid,” “Love You While I Can,” and “Got to Move On” show the band drawing upon the same unique mixture of pop, R&B, and classical influences that characterized their early work, and Blunstone’s instantly recognizable vocals sound as gorgeous as ever.

We spoke with Blunstone about the band’s new album, their distinctly atypical career, and how he manages at 77 to sing like someone 50 years his junior.

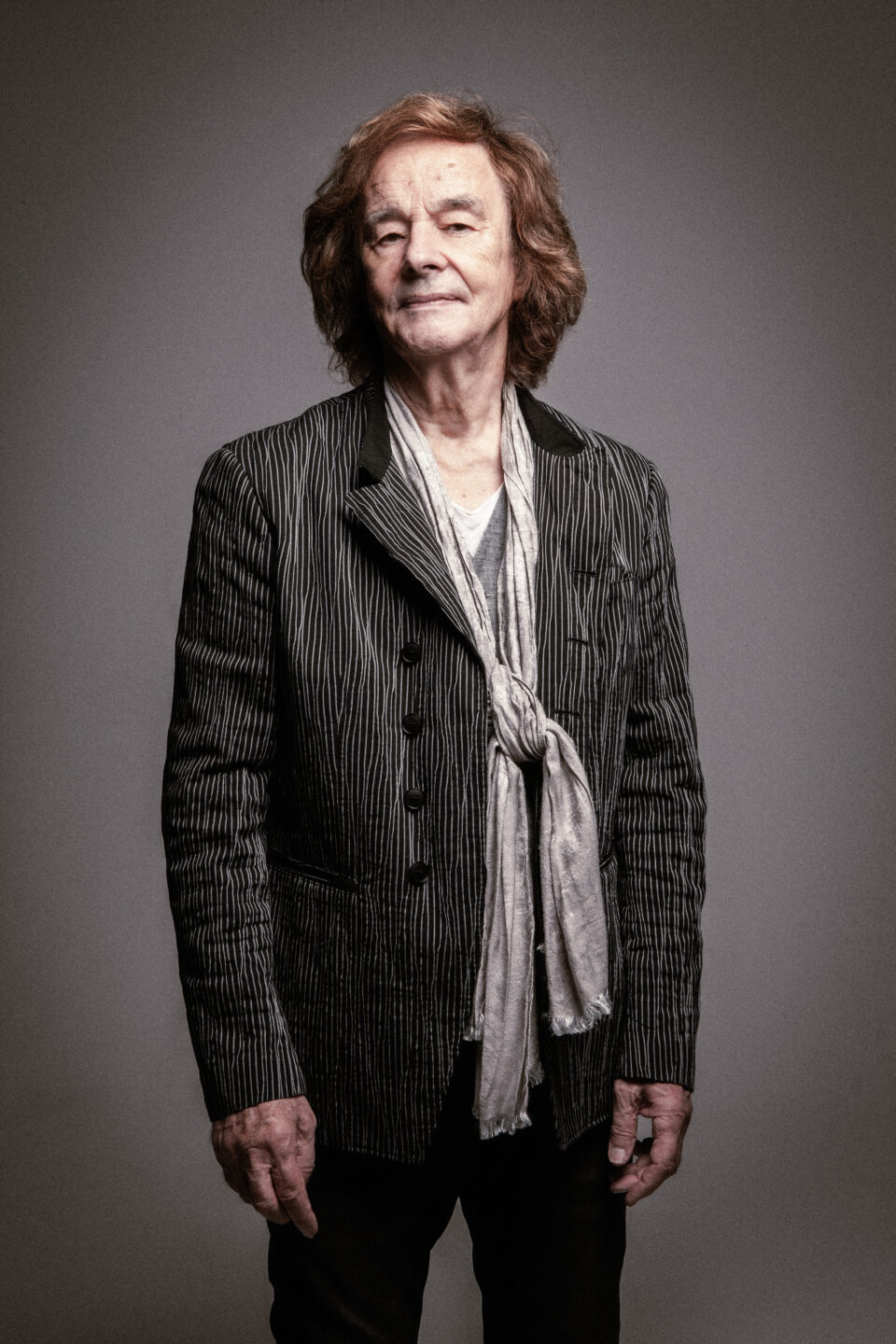

The Zombies – Photography by ALEX LAKE insta @twoshortdays WWW.TWOSHORTDAYS.COM

You played SXSW back in March, and the forthcoming Zombies documentary debuted there at the same time. It must have been a little surreal to be promoting a new album while also looking back at footage of yourself from nearly 60 years ago.

I think it made all of us feel quite emotional. And I think it’s quite an emotional documentary anyway, because The Zombies have not had a traditional career. There’s been a lot of ups and downs in the Zombies story, and all these years later we seem to be reestablishing ourselves. I’m not sure anyone else has ever done that. And believe me, there’s no master plan [laughs]. Rod and I got back together again in 1999, originally to play six concerts. And Rod was quite adamant that he didn’t really want to commit to more than that, but he enjoyed it. We were originally just gonna do those six dates in 1999, and here we are 24 years later, still playing.

We started off playing really small dates in rooms at the back of pubs and things like that. And we’ve just built up quite a formidable fan base since then, just by continually touring and always trying to write new material. I don’t think people realize we’ve recorded as many albums as we have since getting back together. So it’s interesting when a documentary comes along about the past. With a lot of interviews, people want to talk about the past, and they’re fascinated by the ’60s. But we do try to introduce what we’re doing at the moment as well, if we can. That’s where we get our energy.

“Rod and I got back together again in 1999, originally to play six concerts… And here we are 24 years later, still playing.”

Your voice sounds fantastic on Different Game. How have you managed to still sound like you did when you were in your twenties?

I was introduced to a singing coach about 15 or 20 years ago, Ian Adam, who works coaching the singers from West End musicals; he introduced me to a little bit of singing technique, which really helped me, and gave me a set of exercises to practice with. It’s about 35 minutes, and I do it religiously before soundcheck and then again before the show. And of course I do it before recording sessions as well, and I find that it really keeps my voice healthy. When I was 20, I didn’t do any singing exercises, and I stayed up all night and drank lots of beer. You just have to be a little more sensible as you get older.

When did you realize that you had that voice?

Well, there’s probably two answers to that. I met one of my old neighbors quite recently, and she said to me, “Before we knew your name, we used to call you ‘The Boy Who Always Sings’” [laughs]. So I’ve always been a singer, but that doesn’t make you a good singer.

And then at our first [Zombies] rehearsal, this was when it really came home to me. Rod was gonna be the lead singer in the band. I was the rhythm guitarist; I thought I was gonna stand at the back of the stage looking at my shoes. No thought of being in the middle at the front; I think that would’ve really put me off, because I was very shy. There wasn’t gonna be a piano in the band, but at a break in the rehearsal Rod went over to an old piano and played “Nut Rocker” by B. Bumble and the Stingers. And I was absolutely amazed—I’d only just met him, so I was being a bit forward, but I said to him, “You should play keyboards in the band!” And he said, “No, this is a rock band, we want all guitars; we don’t want keyboards.” It wasn’t fashionable at the time to have keyboards, so that was the end of that conversation.

At the end of the rehearsal, I was just putting my guitar away, and “The Boy Who Always Sings” started singing to himself. I sang, “It’s Late” by Ricky Nelson, and Rod looked at me and he said, ‘I tell you what—if you’ll be the lead singer, I’ll play keyboards” [laughs].

“People are always looking for a reason to not write about you. And now it’s because we’re a ‘classic’ band that records new material. There aren’t many ’60s bands still touring that write and record new material.”

There’s always been a big R&B influence running through The Zombies’ music. But since you mentioned Ricky Nelson, what were some of the band’s other formative influences?

Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley, and Little Richard—they were the three people who got me interested in music. But I’ve always thought that we drew our inspiration from a really wide spectrum of music. And it starts with classical and modern jazz, and then blues, rhythm and blues, rock and roll, and pop. And that’s been our advantage in that we sound different because of our wide variety of influences; but in a way, it can be a disadvantage as well, because the industry likes to categorize your music. Certain magazines will only cover you if you play a certain kind of music. Certain radio stations will only play you if you play a certain kind of music. People are always looking for a reason to not play or not write about you. And now it’s because we’re a “classic” band that records new material. When you stop to think about it, there aren’t many ’60s bands still touring that write and record new material.

The Zombies – Photography by ALEX LAKE insta @twoshortdays WWW.TWOSHORTDAYS.COM

You had to contend with so much to make Different Game—there were the COVID delays, and then this was your first record without bassist Jim Rodford, who died not long before you started the album. So I don’t think anyone would have blamed you for throwing in the towel at that point.

I think one of Rod’s greatest assets is that he’s very tenacious. We started two tracks before the pandemic, and it was never in any doubt that, if it was at all physically possible, we would finish this album. It was made more difficult because, we realized on the last album, we really like to record with us all in the room at the same time. In a lot of recording nowadays, people record separately, but we find there’s a different energy in the studio when we’re all there recording together. A lot of those vocals on the album are live vocals; the band plays differently if I’m singing, and I sing differently if I’m playing with the band. So, you know, in many ways it’s nearly a live album, but recorded in a studio environment.

“I think some people would expect us to repeat closely what we’ve done in the past, but it’s never been our intention to do that… We can’t go on re-recording Odessey and Oracle; we have to move forward.”

Jim had been playing with you and Rod since you got back together. Was it difficult to carry on without him?

He was a superb musician and a wonderful performer, and in many ways he was the cornerstone of this band. He could bring people together if there was a problem. He was very sensible, a great calming presence in the band. So when he had his terrible accident, the first conversation we had was whether the band should continue; we had to make a really quick decision because we were due to play in New York in about 10 days’ time. But Jim lived for performing, and we quickly decided to keep the band going. We were very fortunate to find Søren, who we were introduced to by a friend of a friend; he already knew all the bass parts and the harmonies, and he was note-perfect from our first play-through. But of course Jim is really sadly missed.

Different Game feels very much of a piece with your past body of work, but it also sounds really fresh and vital.

Oh, thank you. I think some people would expect us to repeat closely what we’ve done in the past, but it’s never been our intention to do that. I mean, obviously we’re thrilled that Odessey and Oracle has gotten the recognition that it has, but we can’t go on re-recording Odessey and Oracle; we have to move forward. I think there’s a very obvious link between Odessey and Oracle and what we’re doing now, and it’s easily explained because we have the dominant writer from The Zombies involved in this band, and we’ve got the lead singer from The Zombies involved in this band. So in a way, it would be a surprise if there wasn’t an obvious link to the original band. We don’t have to try—it’s genuine, it’s real. FL