When post-punk pioneers Bauhaus canceled their reunion tour last year in order for vocalist Peter Murphy to enter rehab, fans feared it would be a long time before there would be another chance to see the band members in action again. But the group’s guitarist Daniel Ash, bassist David J., and drummer Kevin Haskins have been in this situation before: when Bauhaus first disbanded in 1983, they went on to form the equally beloved alternative rock trio Love and Rockets.

They’ve followed that pattern again now, resurrecting Love and Rockets for a tour that started this past weekend with a much-anticipated appearance at Cruel World Festival in LA, in addition to reissuing the band’s first six albums on vinyl through the first half of this year. Calling from his home in the mountains north of Los Angeles, Daniel Ash explains how he knows when Love and Rockets needs to exist, the unlikely source of his lyrics, and how the project fits in with the rest of his legendary career.

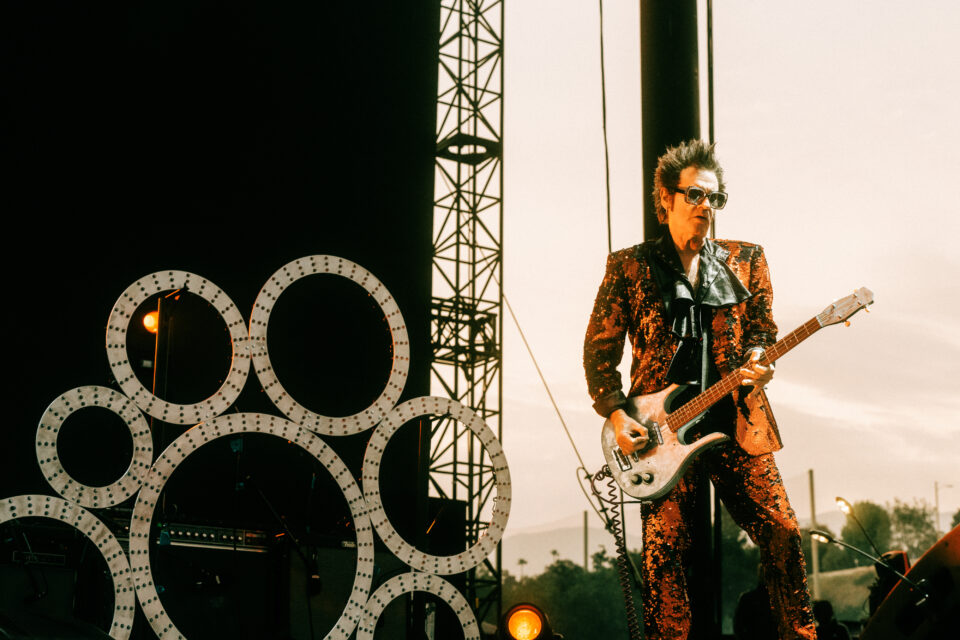

Cruel World Festival 2023 / photo by Pooneh Ghana

It’s been a while since the three of you played as Love and Rockets.

I think it’s been 13 years or something. Everybody’s reminding me that I said I’ll never do this again, but [saying that] is what happens when you go on the road for months at a time and you play the same songs. I’ve had 13 years to recover from that, so it’s time to do it again. Personally, I was very surprised at the amount of interest. I was surprised that we were offered the [Cruel World Festival] gig. I’m surprised that the [tour] ticket sales are really good. It’s amazing. We’re very flattered and excited about it. I can’t put my finger on why people still want to hear this stuff now; it’s just happening. It’s stood the test of time, obviously, the music that we made.

When Bauhaus ended after the tour dates last year, how did you know that you should resurrect Love and Rockets?

This offer [to play the Cruel World] just came out of the blue, and it was a really good offer, so we basically talked about it and said yeah, why not? And then, as always happens, after we get a big festival like that we get offered all these other gigs. So it’s turned into a 16-date tour.

“I said I’ll never do this again, but saying that is what happens when you go on the road for months at a time... I’ve had 13 years to recover from that, so it’s time to do it again.”

How did the three of you realize you’d work well together as a separate band after Bauhaus first disbanded in 1983?

That started off when we were recording the last Bauhaus album [from the band’s original run], Burning From the Inside. Peter had had double pneumonia, so he wasn’t in the studio for the first two weeks, so it was just us three. Initially, we were just going to do backing tracks, but as it turned out, David and myself had some songs ourselves that were fully realized—so we recorded them. After Bauhaus broke up, we remembered the chemistry we had in those sessions when Pete wasn’t there.

How did you decide to also reissue Love and Rockets albums on vinyl now?

About six months ago, Beggar’s Banquet said they wanted to put out the Love and Rockets back catalog. So that, by coincidence, is like synchronicity because that’s worked perfectly for when we’re going to be on the road. I sent [the albums] off to my brother in England. He’s one of these guys who puts albums in alphabetical order, and I’m the complete opposite—my stuff is all over the place. I’ve sent everything through the years to him, so when I’m really old, sitting in a chair somewhere, I can look at it all and reminisce.

How did you decide which unreleased tracks to include on these reissues?

There’s a couple of tracks where we were like, “Absolutely not, that’s not going out, it’s embarrassing, no way is that going on.” But basically, pretty much everything [else] that we never released is on there.

As you’ve revisited your Love and Rockets work with these reissues, have you noticed any particular themes that you’ve tried to get across with your songs?

With Love and Rockets, the songs are either about women or the cosmos; pretty much. When the three of us would travel to a rehearsal room or a studio, we’d be in the car and David and myself would always start going off on the cosmos: “What’s it all about?” Those questions that we all have. And we would go on and on and on. I remember seeing Kevin rolling his eyes, going, “Here they go again.” So those are the two themes that run through all of the records. I think that’s really universal, if you think about it.

“I can’t put my finger on why people still want to hear this stuff now; it’s just happening. It’s stood the test of time, obviously.”

How did you learn to write lyrics like that?

On most of my stuff, I use the “cut up” idea where I get headlines from newspapers and cut them all out, put them on the table, rearrange them, and get a lyric out of them. I know David Bowie used that at one stage, and I think he got the idea from William Burroughs. It’s great; it frees you up [if] you don’t know what to write about. I use the National Enquirer a lot—they have the best headlines. And things like People magazine and gossip columns. It’s a lot of fun doing it this way because it suggests something you wouldn’t necessarily think about at all. It’s much easier, for me, to write that way than any other way.

Cruel World Festival 2023 / photo by Pooneh Ghana

How did you know that you should be a musician in the first place?

Like everybody else at about 12 years old, if not before, you really get into music. Then when David Bowie came along and that whole glam rock thing, and then punk a few years after that, I was like, “This is what I want to do.” Same with the rest of the guys. The idea of doing a nine to five just wasn’t an option. It’s a certain mindset that you have. And luckily, it worked out.

What do you think would have happened to you if it hadn’t?

I don’t even want to think about that. Well, I was trained at art school for four years to do graphics. I did have one interview for this job designing cartons for Weetabix, the cereal company. I really didn’t want the job, but my dad was forcing me to go to this interview. There were a few hundred people going for it, and I got into the top six [finalists]. I was so scared that I might just get this damn job. Luckily, I didn’t. I remember driving away from the place in this old banger of a car that I had at the time, and I was looking in the rearview mirror and the Weetabix sign was getting smaller and smaller, and I was very happy.

What do you think as you look back on your career and the legacy you’ve built?

I really don’t think about that. I just think about right now, and the future. I don’t reminisce about the past—not as far as the bands are concerned. When the band is done, I don’t listen to that stuff anymore, I go on to something new. So far, so good. FL