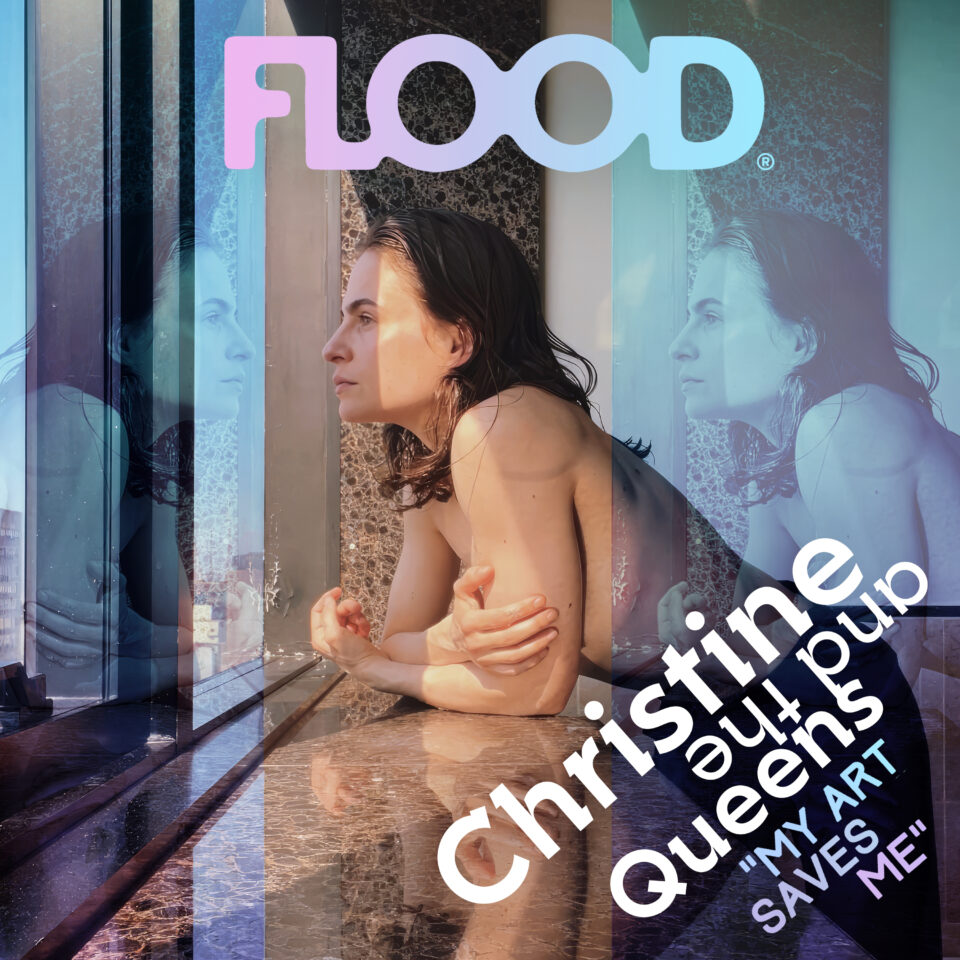

Primavera Sound is interfering with Héloïse Letissier’s rest. Letissier, professionally known as Christine and the Queens, is performing the prime midnight slot at the top-tier Barcelona festival tonight. Music from the previous day permeated Letissier’s room into the early morning hours, a fallout from staying in a hotel across the way from the festival grounds. But Letissier is no worse for the wear. His eyes are clear. His shoulder-length hair is combed back. His black tank top shows off his dancer’s arms. He looks luminous—if a little trepidatious about discussing his latest album, Paranoïa, Angels, True Love.

It’s been four years since Letissier lost his mother, but the pain hasn’t dulled much. “I’ve been wondering if I should talk around this record,” he says over Zoom, where his screen name reads “Red”—short for “Redcar,” one of the artist’s many names over recent years. “I could see myself having to revisit that pain. It still very much is the heartbreak of my life. But my art saves me, in a way, provides me with structure in my bones, makes me want to live for the next day.”

Letissier uses dramatic words to describe his thoughts and feelings. He punctuates his sentences with the French words quoi (what), mais (but) and en fait (in fact). He changes names seemingly with each album release, highlighting his many sides and keeping fans and journalists on their toes. However you address him, he will answer. One thing is for certain: whatever is happening inside Letissier comes out in his art, his lyrics, his music, his wonderfully expressive dancing, unfettered and pure. He doesn’t stop his tears from falling intermittently during our conversation, and he doesn’t wipe them away either.

“My art saves me, in a way, provides me with structure in my bones, makes me want to live for the next day.”

With each album release, Letissier turns a major corner in life. This goes back to his 2014 debut, Chaleur humaine (French for “human warmth,” and alternately titled Christine and the Queens), which came four years after the French native went through a major heartbreak and left his studies at a theater conservatory. Inspired by the drag queens at London’s iconic venue Madame Jojo’s, Letissier created the Christine persona and added “the Queens” as an homage to those at Jojo’s. Letissier’s pansexuality is threaded through Chaleur humaine, including on the quirky earworm “Tilted.” On its follow-up, 2018’s Chris, Letissier further explored masculinity on standouts like “Girlfriend,” and announced that the album title was also his new name.

In 2019, between Coachella weekends, Letissier’s mother died suddenly, leaving him devastated and encouraging him to (rightly) cancel the second weekend’s performance. Last year’s Redcar les adorable étoiles (Prologue)—primarily sung in French—and the new Paranoïa, Angels, True Love are reflections of this loss and function as companion albums of sorts. At the time of the former, Letissier adopted the Redcar moniker and wore a single red leather glove.

Prior to Redcar’s release, he announced he had begun gendering himself as male, then had to unnecessarily defend, rationalize, and explain this development on social media. The reactionary album was recorded within a two-week stretch in Paris, after the completion of Paranoïa, Angels, True Love. Redcar received mixed reception from critics while he struggled through the promotional cycle—both physically from an injury and emotionally from the loss of his mother, as well as from yet another heartbreak.

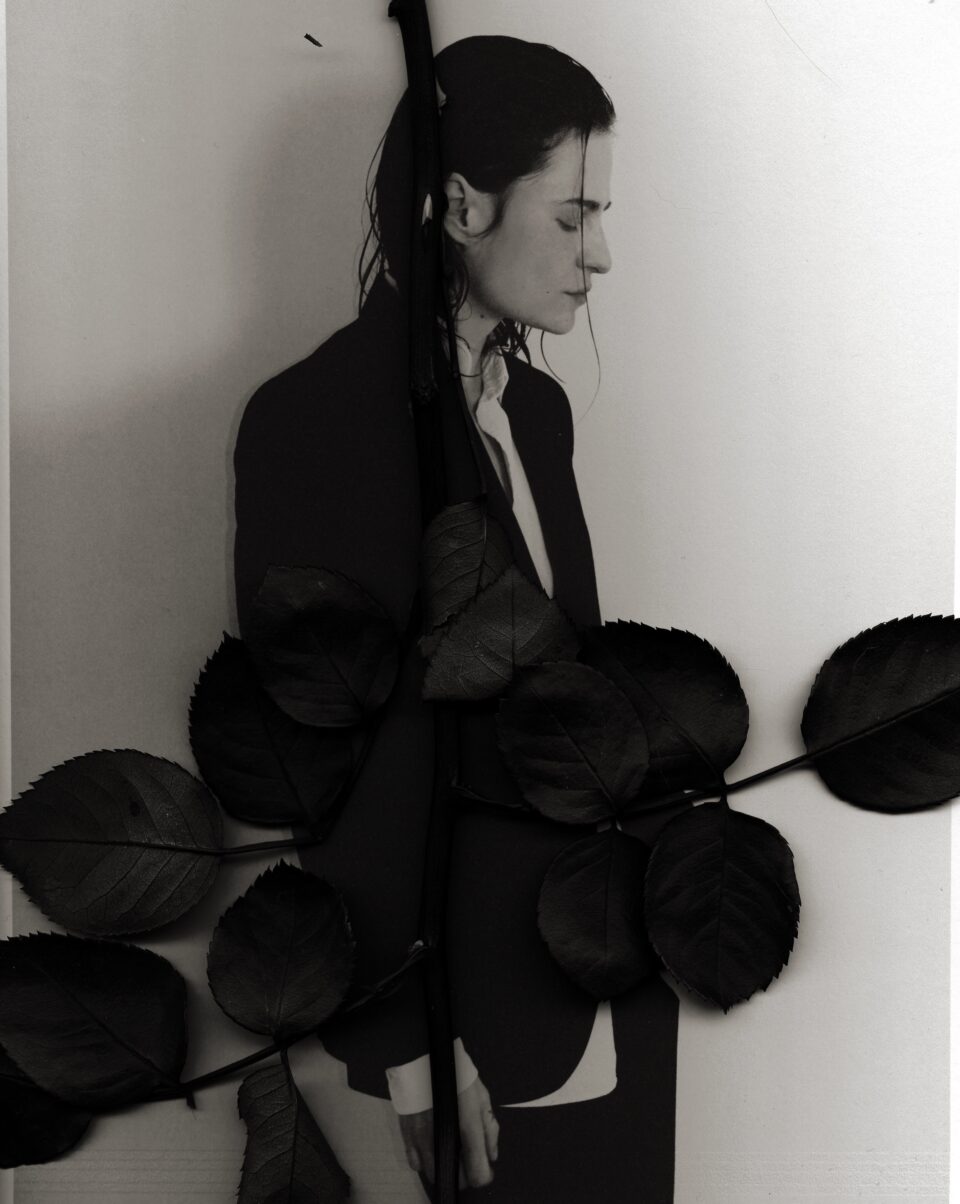

Jasa Muller

Yet, as he told The Guardian at the time of Redcar’s November 2022 release, “When my mother was alive, I think I had to be a daughter for her. And, by the way, I loved her, so I was not super mad about this. But there was a huge chunk of me that did not even connect, I think, to my trans identity when she was alive, because to be feminine was an element of what she needed also.” In the same Guardian interview, Letissier also expresses resistance to the “hormones and operations” associated with trans identity, stating, “I don’t owe anyone scars.”

Talking about the making of the albums may not be helpful to Letissier, but the creation of them definitely was. “The soothing part of it was to become as brave as I could, as precise as I could in my practice,” he says. “I do it for us. I do it for all the beautiful things she made me fall in love with. But I was very de-socialized. I was praying all the time. I did my inner questing, my shamanic journeys to try and understand the multi-dimensionality of the grief. I disappeared into the practice. I couldn’t relate to people. Music always was a shelter, a cathedral of light for me. But this time it was the asylum in the cathedral. I was there all the time. I was gone in the music.”

“Music always was a shelter, a cathedral of light for me. But this time it was the asylum in the cathedral. I was there all the time. I was gone in the music.”

Letissier’s raw, unfiltered emotion has connected with many, including actress/model Louise Donegan, girlfriend to super-producer/mixer and musician Mike Dean. Donegan introduced Dean to the music, which led to Dean sliding into Letissier’s DMs, suggesting they work together. “The musicality of what [Letissier] has created in the past is extraordinary,” says Dean over email.

In 2021, Letissier found his way to Dean in Los Angeles—a city that isn’t the most nurturing to non-residents, and which can feel isolating, particularly if you’re in an emotionally fragile state. It’s the city Letissier was in when he received the news of his mother’s passing.

“That made me want to turn back to it,” he says. “The story I have with Los Angeles is of empowerment, of finding my truth, of being myself. I love France. I love living in Paris, but for who I’m becoming, for my reality as a man, for my freedom, the otherness I needed [in order] to be myself—I experienced it in another city. Paris feels like a trap, the trap of me being overexposed at 24, dysphoric. It was great, but I feel trapped in the past. The oddness of Los Angeles was perfect. I feel comfortable there because I feel like I can reinvent things.”

Paranoïa, Angels, True Love was written in a house in Los Angeles’ Los Feliz neighborhood that Letissier assures me is haunted. Initially, he was in Dean’s studio, but soon realized he had to work on the songs on his own and bring them back to Dean for co-production. Early mornings proved to be the magic time for Letissier, which he surrendered to without overthinking it. “I wanted to heal, I wanted the music to save me,” he says. “I was a bit insane by grief, but also ready to unleash. I don’t think I could have opened up this way with just anybody. I was blessed with this coincidence of meeting [Dean], someone who could let me rage, relate to music in an extreme way and never tarnish that. It felt quite guided and appropriate.”

“Music heals. My studio is in my house, so we make music and then eat together, family style. We embraced [Chris] into the heart of our musical family.” — Mike Dean

“I, too, have suffered many personal losses in my time on this planet, and I felt a deep connecting empathy with that raw emotion,” adds Dean. “Music heals. My studio is in my house, so we make music and then eat together, family style. We embraced him into the heart of our musical family.”

Letissier and Dean bonded over the Bristol Trip-Hop Holy Trinity of Massive Attack, Tricky, and Portishead, as well as various other musical influences such as Malcolm McLaren, Marvin Gaye, Freddie Mercury, and The Who’s Tommy. The sonic inspiration is apparent on the decidedly trip-hop sensibilities of Paranoïa, Angels, True Love. “Tears Can Be So Soft” has the dark dissonance of Massive Attack’s “Teardrop” and features a sample from “Feel My Love Inside” by Marvin Gaye, who also gets name-checked on the dreamy “Marvin Descending.” The elegiac orchestrations of “Full of Life” are a sharp contrast against the drum ’n’ bass beats skittering through “Track 10.”

What’s on Letissier’s current playlist is likely reflected on the lineup of this year’s Meltdown Festival, which he curated—following in the footsteps of David Bowie, Patti Smith, and Robert Smith, and which kicks off on the same day as Paranoïa, Angels, True Love’s release.

The album’s 20 songs, which clock at just under 100 minutes, are arranged in three movements. 070 Shake (whose track “Body” Letissier appeared on in 2022) is featured on the titular “True Love” and its partner piece, the frantic “Let Me Touch You Once.” But perhaps the most unexpected presence on Paranoïa, Angels, True Love is Madonna, whose appearance on “Angels Crying in My Bed,” “I Met an Angel,” and “Lick the Light Out” creates cacophonies.

Madonna is “the voice of everything,” according to Letissier. “It could be the dystopian voice of simulation, it could be the Holy Mary, it could be my own mum. I respected her before, and I do even more now, because she seems to look at the thing with the poet’s eyes, quite precise. The way she delivered was very exquisite, very moving.”

“I wanted to heal, I wanted the music to save me. I was a bit insane by grief, but also ready to unleash.”

Paranoïa, Angels, True Love’s cover depicts Letissier as a marble carving, possibly an angel, which quite obviously figures largely into both this album and Redcar. This fascination and association with angels began at the time of Letissier’s mother’s passing and continued growing. Mike Nichols’ award-winning HBO miniseries based on Tony Kushner’s 1991 play Angels in America resurfaced for Letissier during lockdown.

“I like to put to myself a canvas that gives me a structure,” says Letissier of his adoption of the series’s framework. “The arrival of angels, that terror of the flesh, the fact that the invisible was populated with those creatures, that I needed the invisible to be populated with myself—I just fell in love with that canvas. I decided that the record would be shaped with this core idea of angels appearing. It was almost me praying for them to appear. You can tell it is musicians who dreamt about theater rather than a hard canvas.”

Be that as it may, theater is in Letissier’s blood and ingrained in his life from an early age with formal training in dance and drama. Presenting his music through movement is as much part of his expression as its sonic aspect. His choreography is natural yet deeply emotive. Every gesture is nuanced and carefully placed; its delivery intentional, never extraneous.

“Dance functions at the core of everything,” says Letissier. “It’s so intertwined with the theatrical expression in the body, where it comes from. Every record is always, ‘How am I going to move inside of it?’ The records redefine the relationship to the body. I literally shelter my humanity and I make a lot of sense of things through dance. It’s part of the language that exceeds the words I rely on.

“Dance functions at the core of everything. It’s so intertwined with the theatrical expression in the body, where it comes from. Every record is always, ‘How am I going to move inside of it?’”

“This record, in particular, questioned me a lot about dance,” he continues. “It was kind of a hammer breaking all the certainties I had about everything. I had to think differently of dance, more extremely even, to go back to the core of why I was moving, to develop the notion of performance, of choreography, of perfection, and to think of angel bones, which was almost at first a question of immobility. The dancers who give me the most emotions are the ones with imagination. They live the whole story and it puts so much intention in the body, so much vibration. Theirs is very skilled choreography—if it’s empty from the heart, it’s just agitation to me.”

Through movement, through Paranoïa, Angels, True Love’s three-part title, through the inspiration of Angels in America, the album has unintentionally—or intentionally—developed in three acts, which, Letissier says “became solidified as I was doing the work, the title I already had in my head for two years.” But, he admits, “I haven’t figured out what true love is enough to even claim that last part.” FL