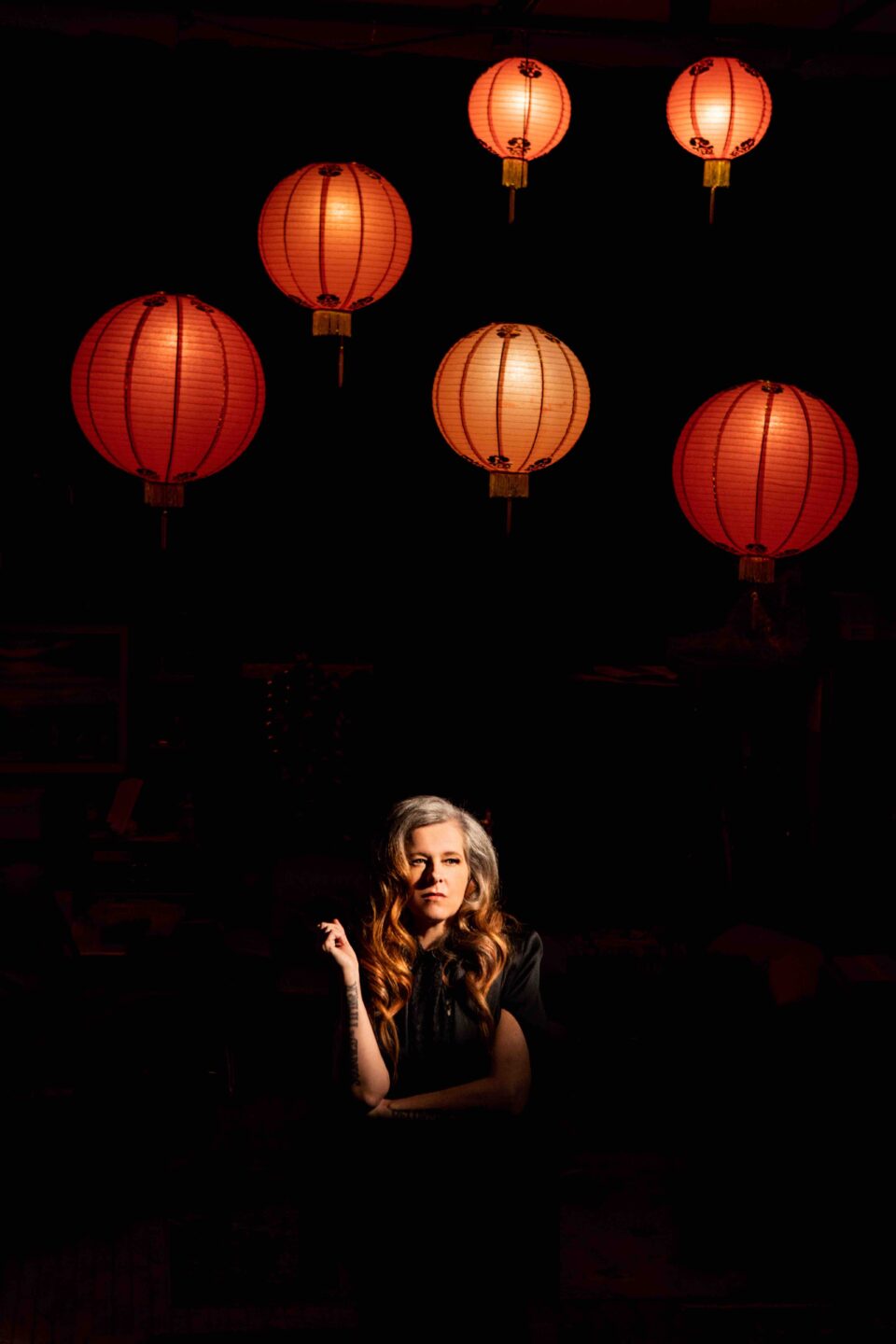

For the past quarter century, and across seven critically acclaimed studio albums, Neko Case has solidified her reputation as a highly unique and innovative songwriter. Her work, which is often beautiful yet haunting, veers from country and Americana to folk- and indie-rock, though her emotive vocals have always remained the centerpiece as she tells cryptic but relatable stories with her lyrics.

So it seems fitting that the New Pornographers co-founder has finally released a solo-career-spanning retrospective, Wild Creatures—the digital version came out last year, and now the CD and double-LP vinyl versions followed at the end of this past June. Wild Creatures features 22 tracks, drawn from across her career, plus one new song, “Oh, Shadowless.” She originally intended to include it on her last album, 2018’s Hell-On, but hadn’t finished it in time—now it seems like a fitting finale for this collection. Altogether, it’s an impressive overview of her chameleonic musical abilities.

As if anyone needed more convincing about Case’s talents, numerous highly respected artists wrote essays or “guest commentary” for Case’s immersive website, singing her praises to mark Wild Creatures’s release. Contributors include Shirley Manson, David Byrne, Jeff Tweedy, Amy Ray of Indigo Girls, Rosanne Cash, Andrew Bird, and Jason Isbell, among many others.

As she takes the measure of her career, in our recent conversation Case admits that it took her a long time to believe that she’s actually a well-established and highly regarded professional musician. Certainly, though, Wild Creatures confirms her legacy, once and for all. We discussed this realization and more in the chat below.

How did you decide it was the right time to release a retrospective album?

It was an idea that my record company had. I’ve been working on a new record, but it wasn’t going to come out anytime soon, and they were like, “You have so much stuff—why don’t we do something?” And I was like, “Sure, love that!”

How did you decide what songs to put on it? You have so many you could’ve chosen.

I’m way too close to them, so I asked [ANTI- Records president] Andy Kaulkin to choose the initial round, and then I took some things out and put some things in. So he made it a lot easier for me. And he wanted to do it, too, because he’s just one of those people. He’s the playlist maker. He was really excited to do it.

“Music is not sport. There’s room for everybody. I’ve never had that competitive feeling toward other people.”

Did putting this together conjure up any particular memories for you?

I remembered all the years I’ve been touring, and I felt a little sad about how little I remembered. Like, I remember the big things and some really weird small things, but I think there’s a lot of stuff that I was probably so anxious about—I was just using all of my energy for forward motion, getting to the next place. It’s not that I don’t remember those times or don’t appreciate them; I just wish I could sit in them like a hot tub a little more.

Some would say that you need to work that hard if you’re going to make it in the music business, because it’s so competitive.

I guess, but I also know—and I’ve always known—that music is not sport. There’s room for everybody. I’ve never had that competitive feeling toward other people. Art is not a sports model, but we use sports methods to measure it, and it’s really a disservice. Ranking systems are things that I really, really loathe. It makes people feel bad. I understand about “What song sold the most this week” or something, but it’s kind of a sad barometer for art, in a way.

We portray art as though there’s only this tiny, tiny little piece that can be beneficial, or can be big or famous. I’ve had friends before that were like, “So-and-so is getting all this attention, man! We should be playing that show!” It’s like, “No, you’ll be playing some show and it’ll be great and you’ve got to love it when it’s happening. But there’s not a world where somebody is taking something away from you.” It’s such a strange mentality to me. But I see it makes people unhappy, and then they don’t enjoy what they’re doing, which was supposedly the whole point.

A minute ago you said you worked so hard all the time, and you didn’t always let yourself enjoy it—so what was your motivation, then?

It was very abstract. It was like, “I’ve got to go to the next show, and I have to do a good job because I won’t get another show, or nobody will know that I make records.” It was more like a dog who doesn’t know where his next meal is coming from, rather than competitive. It was like a weird survival instinct thing. There’s a lot of mythology in the music business about, “You’ve got to strike now or it’s going to dry up.” Which is also kind of bullshit. I’m definitely not as frantic now, but it’s hard to shake that feeling, even though at the show I’m definitely much more present than I’ve ever been. It’s not to say I wasn’t present during those old times; I just was more afraid in my life.

“There’s a lot of mythology in the music business about, ‘You’ve got to strike now or it’s going to dry up.’ Which is kind of bullshit... It’s hard to shake that feeling.”

Given that being a professional musician can be difficult, how did you know you were meant to do this work in the first place?

It’s all I ever wanted, and I never would admit it to myself. It was the elephant in the room all the time. I was a girl brought up in the Gen X [attitude of], “Girls can’t do that.” Nobody was encouraging me. I grew up in the Reagan era where music and art were being taken out of public school. Music and art were popularly mocked as things that were pipe dreams, even in popular culture. I guess the desire was such that it was a river I was already up to my waist in, and so the current was there.

What was the moment when you realized it was actually working out as a career for you?

I remember the first time I called myself a musician. I was in my early thirties, and it was because I had to write it on a tax return. It was like, “Oh shit, I made money playing music—I’m a musician, and that’s what I have to put on here.” It was so startling. I felt kind of like a fraud writing it down. But playing music up to that point was always like, “Hey, this could be gone tomorrow,” so I wasn’t gearing up for, “I want to be a musician and I’m going to do this, this, and this.” It wasn’t like that until maybe my forties.

It was probably a lot clearer to other people that you were on your way long before it was to you.

Yeah, which is a very common, very sad reflection of American society underestimating all female-identifying people and non-gendered status. We were just so underestimated and so underrepresented, it was hard. We were always just like wallpaper, not really in any major role. I remember looking at bands and videos and record covers. Whenever there was a woman on the cover of a record, with the exception of Donna Summer and Dolly Parton, usually they were posing, like the cover of Candy-O. There was way more of that than there were women on the cover of their own record, especially in rock and roll music.

“Whenever there was a woman on the cover of a record, usually they were posing, like the cover of Candy-O. There was way more of that than there were women on the cover of their own record.”

Judging by all the artists singing your praises on your website, you’ve helped make things better for women in rock. How did you know who to ask to contribute quotes for that?

I didn’t ask them—my manager did it as kind of a surprise, because she’s a really nice person. I was really gobsmacked and overwhelmed and cried a lot [when I saw the contributions]. I was so overwhelmed that people wanted to say anything at all. I’m still not over it.

What do you think it is about your work that’s enabled you to connect so strongly with listeners?

I think people like stories, and they like to hear the language they speak used in a playful way, maybe. I hope that’s what it is. People have told me that sometimes a turn of phrase will evoke a feeling they couldn’t access another way. And that can be a good or a bad thing. But it always makes me feel good if that helps someone to realize something. FL