On 2018’s Springtime and Blind and 2021’s Between the Richness, Pat Flynn, singer of Massachusetts post-hardcore band Fiddlehead, brandished his grief as a badge of honor. With a voice both melodic and strident, his role in the band has been to make sense of his feelings, of which there are many; those of immense loss set into motion by his father passing in 2010; the unbridled joy at the birth of his kids; the influence and responsibility of working with young minds as a high school history teacher. Fiddlehead’s ardent third album Death Is Nothing to Us finds the singer at a crossroads with grief and wrestling with facets of denial and perseverance, his voice reaching for resolve within a tracklist of relentless and poignant punk rock.

From a Zoom call in his home office, the husband and father of two makes clear that he didn’t intend to make a thematic trilogy. “It was totally organic, coincidental—no long-term plan there,” he says, speaking in a clear and concise tone that I could best describe as “teacher-voice.” This clarification followed a series of quotidian domestic events: he left the sprinkler on all night in the yard, his mother called to ask for help moving out of her office, his toddler barged into the room to say hello. The core of his impetus as a writer is summed up in this duality: the wholesome stability of his family life and the ambience of death that’s coated his understanding of existence from a young age.

On the verge of Fiddlehead’s newest release, we spoke with Flynn about the stages of grief, his reverence for punk culture, balancing teaching and music, the influences of Fugazi and Raymond Carver, and how death and family shaped the perspective of Death Is Nothing to Us.

It seems like you’re sort of a Henry Rollins–level punk rock historian. Did your love for cataloging punk inspire you to become a history teacher?

The timeframe in which I was born was fairly interesting, having two older siblings that had specific tastes for punk-inspired rock music. I was born in ’85, my brother was born in ’80, so he was 11 or 12 when Nevermind came out and went really deep with it. For my brother it wasn’t just radio music, it was a doorway into discovering what created Nirvana—like how a band like Scratch Acid informed how to interpret certain melodic decisions made by Nirvana, for example. Point being, my siblings knew how to dig deep, and I followed along to question the causal equation of why things are the way that they are. It’s a little retrospective, but the idea of digging and trying to explain causation—that’s doing history.

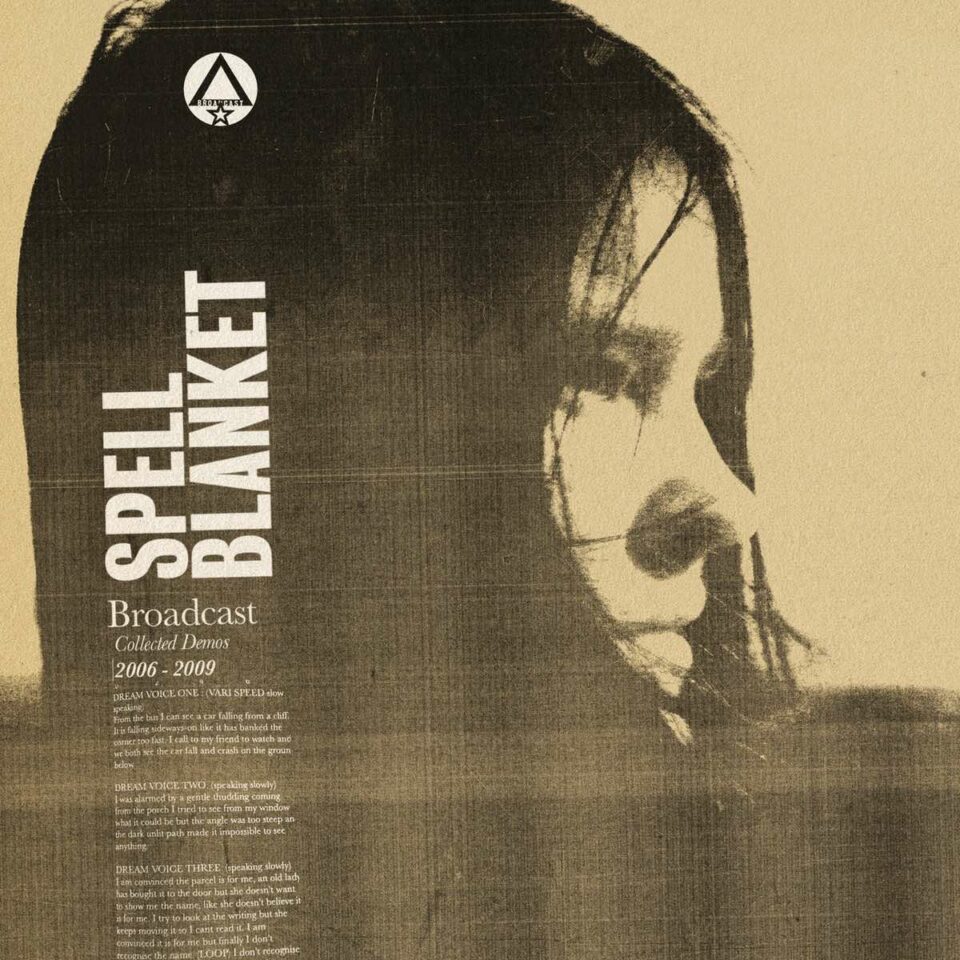

Being in punk and hardcore was learning this method of recognizing that little things are actually quite big. Like discovering Minor Threat. That wasn’t radio rock, that wasn’t popular. They had this tiny little discography, a record with a photograph of a depressed-looking guy on the cover. But I remember listening to it and my whole world changed. The idea that little things can actually be really big if you lean into it and think about more than just its popularity, that helped me understand certain ways of doing history.

“The idea that little things can actually be really big if you lean into it and think about more than just its popularity, that helped me understand certain ways of doing history.”

I’ve recently been lobbying a friend who’s Fugazi-curious to get sucked into the wormhole of it.

I’m very opinionated on Fugazi. This is stuff that Fiddlehead could talk about for hours. One thing we like to do in the band is imagine how to make a band’s discography better by downsizing it to just one record. Not in a greatest-hits way; it has to flow. But with Fugazi you can’t do it with just one record, it has to be two records. I made a playlist of 20 songs that flow. We get really neurotic—

About Fugazi?

About anything [laughs].

If you were going to whittle down your discography, what would make the cut?

Right now I’d just say our new record if I had to whittle it down to one. I’m so happy with how that came out.

Is it weird for you if your students approach you about your music?

Totally not. Historically, my lyrical content is not something I’d be ashamed of having anyone read in any way. I’ve written pretty openly and honestly about death and grief, love and life, dying, sadness. My upbringing in punk music and culture, leaning into the “come as you are” mentality, makes me feel like this is who I am, and if you have a problem with someone expressing their woes, then I don’t know what to tell you. I’m a human being.

“My upbringing in punk makes me feel like this is who I am, and if you have a problem with someone expressing their woes, then I don’t know what to tell you. I’m a human being.”

Being the last album in a coincidental thematic trilogy, you’ve said Death Is Nothing to Us “rounds out some stages of grief that weren’t addressed previously.” How would you describe those stages you’re singing about here?

When I was in middle school I was subjected to death in a pretty strange way. I was an altar boy and I’d get pulled from class a few times a week to serve the day funerals at the church associated with the Catholic school. The day funerals were services where not many—if any—people would be attending. So the churches would be completely empty except for me, another altar boy, the priest, the organ player, and a completely barren pine coffin in the center aisle. And I’d think while I was on my knees participating in the service about how there was a life here that’s lost and forgotten. That really left an impression on me.

I got to high school and took an elective called “Death and Dying,” which I was drawn to having been surrounded by instances of death around me. The course was extremely impactful on me, thinking about death, and sometimes overthinking it. While it was great to take a course essentially on the stages of grief, it caused me to get lost in the trance of the power of death. One of the stages is about the anger of it, and also depression; the last couple records, I felt myself compelled to understand the depressive side through my mother’s eyes and losing my father. Between the Richness, in many respects, is an acceptance record in terms of those stages. [Death Is Nothing to Us] has a variety of it with elements of denial. But the stages aren’t supposed to go in order.

How has having kids changed your perception of your own struggles with mental health?

We’re rebuilding in the cycle of life. We’re keeping it a cycle, as opposed to breaking the cycle. In terms of writing in this band, I’ve been able to look at things as not a process of cycle-breaking, but to just accept that there’s no end stage until you die. The waves of sadness and happiness, they’re always out there because life is always happening. Perhaps it’s better to accept that the cycle can’t be broken, but you can ride it a little bit better.

I guess that kind of explains why our records have a juxtaposition of happiness and sadness all at once. Like the song “Sleepyhead” on the new record, it’s the brightest-sounding song. I remember writing it and thinking, “This is a cross between a Juliana Hatfield song and a Michelle Branch song.” And I love Juliana Hatfield, but I don’t know how I feel about Michelle Branch. So I approached that bright-sounding song and said to myself, “I’m going to pour some darkness on this.”

“The waves of sadness and happiness, they’re always out there because life is always happening. Perhaps it’s better to accept that the cycle can’t be broken, but you can ride it a little bit better.”

I feel a sense of honesty and vitality throughout the record, like how pushing through pain and grief doesn’t always yield happiness, but reveals strength and perseverance. But if you had to choose, would you rather be resilient or happy?

I love Raymond Carver. I think there are some unbelievably amazing philosophical takes on life delivered in single lines. There’s a line, and I forget which story, but it’s a typical Carver character who’s woeful and dealing with failures and a woman leaving him. She’s writing him a letter talking about her happiness and he says, “As if happiness is the only thing that matters.”

There’s another poem of his called “Happiness” about this guy observing life in the morning. He sees these two boys walking, and one of them puts his arm around the other. And that’s it! This wonderful, split-second moment. I don’t think you can have those wonderful, transcendent moments, these tiny, trivial moments, if all you’re doing is trying to look for happiness. It’s a good philosophical question; I’d go with resilience.

Does naming the album “death is nothing to us” mean that you’ve come to the conclusion that you’re not afraid of death?

I don’t fear its power anymore. But I want to see my family and my friends forever. That’s something that haunts me about life, especially if you’ve cultivated very meaningful and close relationships. But the point is to enjoy the ride. I’m driven by working with young people in the classroom, motivated and energized, and a hundredfold when I’m with my little family. FL