It’s not often that a humble indie act’s music seamlessly aligns with the mainstream, but in the mid-’90s, the relatively unknown The Folk Implosion—the duo of Lou Barlow and John Davis—entered wider public consciousness with their soundtrack to Larry Clark’s 1995 movie Kids. Written by a then-19-year-old Harmony Korine, the film turned heads for its graphic depictions of sex and drug use among teenagers, as well as for its verité style. Its soundtrack featured nine songs and incidental pieces recorded by the band for the film, alongside one of Barlow’s previously released songs with his group Sebadoh and tracks by Slint, Daniel Johnston, and Lo Down. Somewhat unexpectedly, it introduced Barlow and Davis’ music to a mainstream audience, and single “Natural One” cracked the Billboard Hot 100’s Top 40.

Yet in the age of streaming, rights shuffling has kept the album from being available on DSPs, and physical copies have been long out of print. As of this month, though, Barlow and Davis have made that music available once again. Music for Kids compiles all the music Barlow and Davis recorded during the original soundtrack sessions, including the nine songs that originally appeared on the album. It also features a pair of remixes, a handful of previously unissued session recordings, and two songs that eventually ended up on their 1997 album Dare to Be Surprised. The album brings a critical alt-cultural moment back to life by returning to streaming and physical media an album—with a hit song, even—that found indie and the mainstream in a rare moment of alignment.

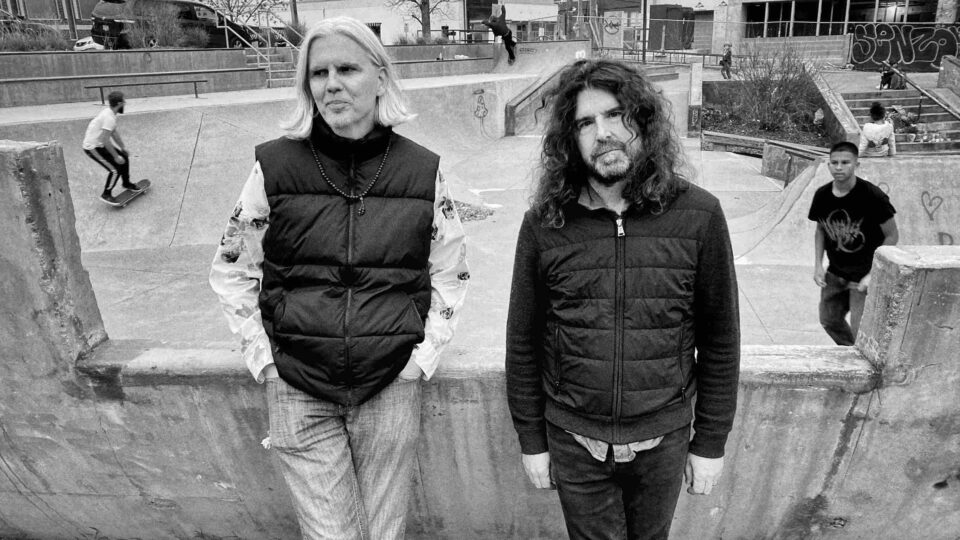

We spoke to Barlow and Davis about the process of getting their soundtrack recordings back in print with Music for Kids, the unexpected consequences of being an underground band with a hit song, and being asked to tour with White Zombie in Southeast Asia.

What was the catalyst for the Music for Kids reissue?

John Davis: A person who helps us collect our publishing for the Kids material encountered someone who had the rights to the masters. I don’t know what the genealogy was of how the movie sold them, but it had been sold a couple times, and this person contacted our lawyer and said, “I’d like to just give this back to them,” basically. I don’t know why he did that, but he sold it to us for one dollar. There’s been a dodgy release history, and people have been asking us, “Why isn’t this on Spotify?” We contacted Domino and they were interested, so we sold the masters to them, and they’ve now released it. But we were very lucky to get the masters back.

How new of an experience was it for you, working on soundtracking a film?

Davis: It was kind of unheard of in that genre [at the time]. J Mascis made music for Gas, Food, Lodging, but it was rare. I was really into film in high school and college, and I lived in a town where there was a very good repertory theater. So having been an independent film buff, I was really interested in soundtracks and interested in how it could make you think about music in a more visual way—like trying to make sound textures that almost sounded like you could see them.

“When ‘Natural One’ started to break, London Records was like ‘White Zombie want you to open for them in Thailand!’ and we were like, ‘We’re not even a band!’” — Lou Barlow

How much of a surprise was it when “Natural One” became a hit?

Lou Barlow: I was definitely surprised. We felt very good about it when we finished it in the studio. It felt like magic for us. It’s amazing to just be in the zone, and you got your mojo and songs are falling together. Shit sounds great when you’re playing it back, and with “Natural One” we kind of did it on the tail of everything we were working on. When people heard it and started to agree, it was cool.

Davis: I think we thought it could be a hit. I think anyone who works in a hi-fi studio and hears their song through a huge speaker thinks their song could be a hit [laughs]. I don’t think that some of the things we were doing with the soundtrack were what Larry and Harmony wanted us to do. I think Harmony certainly wanted more rough, lo-fi offensiveness. I think he liked shock value. I liked the way the film was shot, which is one of the few things I liked about it—like an early-’70s John Cassavetes movie. It had really saturated colors. And the tape hiss kind of matched that.

When [“Natural One”] did become a hit, that was really weird. That did open another series of questions that aren’t about purely creative things. Once it actually becomes a hit you start dealing with stuff that people in our genre hadn’t had any experience with, except for maybe Nirvana. That posed a whole series of pretty intense challenges that were hard to deal with.

“Once you’re on TV, it’s like you must be getting a lot of money, you must be getting this mainstream fame, you’re one of those celebrity people.” — John Davis

How did it change things for you?

Davis: It was really surprising how much you get associated with that mainstream culture—like you’d hear one of our songs on NFL on Fox. There were higher commercial expectations around you at that time. Also, what’s good about lo-fi music is people don’t think, “You’re making me feel like an inferior person.” Once you’re on TV, it’s like you must be getting a lot of money, you must be getting this mainstream fame, you’re one of those celebrity people. Even if you don’t intend to send that message, if you’re marketed through those circuits, it’s like you’re up here and I’m down there. It was weird to feel that people I’d known for years were threatened and intimidated and jealous. And we hadn’t actually even made any money yet.

Barlow: I was kind of prepared for it, because I’d been playing in bands since 1985 and I’d toured extensively. But for John it was a lot more difficult all of a sudden being thrust into this thing. When “Natural One” started to break, London Records was like “White Zombie want you to open for them in Thailand!” and we were like, “We’re not even a band!” [Laughs.] For me it was easy to say “No, we can’t do that.”

It was a one-off, and we weren’t really gonna knuckle down and follow through on this kind of success. I had my band Sebadoh that I was touring with extensively, so I had a distance from it that I could appreciate and say, “Cool, we have a hit.” I wasn’t really expecting a whole lot out of that. I wasn’t going to change direction because of it. But it complicated the road going forward for a lot of people around me, because a hit’s a big deal. The blood’s in the water. It got a little dicey after that.

“Looking back on it, it was like, ‘Oh my god, people kill for that kind of a moment.’ Not to say we squandered it, but we kind of continued on the path we were on anyway.” — Lou Barlow

So you never did open for White Zombie?

Barlow: We never did. We were asked to do a lot of shows in New York and Boston promoting the film. And what we did was we played the shows as “Deluxx Folk Implosion,” which is John and I and [Sebadoh drummer] Bob Fay and Mark Peretta. So we promoted “Natural One” by getting together and playing minute-long screaming punk songs. We didn’t care. The powers that be were probably like “You’re taking a gun and shooting your foot, why are you doing that?!” But I just wanted to keep things fun and casual. Looking back on it, it was like, “Oh my god, people kill for that kind of a moment.” Not to say we squandered it, but we kind of continued on the path we were on anyway.

Twenty-eight years later, how does the music from those sessions resonate with you?

Barlow: It’s bittersweet. When you’re creative and your path kind of intersects with the zeitgeist for that moment—that doesn’t happen a lot. I like how context is that thing that makes music resonant. It’s kind of scary because as a musician, with every project you feel wrapped up in it, like “This is my baby!” But it’s funny how the atmosphere and the culture really do determine how it’s received. That’s the soil, you can plant your seed, but it’s kind of out of your control. Which is something artists find really frustrating. You can pour your fucking heart into it and it can be the best thing you’ve ever done—even objectively, like that’s a superior piece of work. But if you plant it in sand, it’s not gonna go anywhere. But [for us] it was the right time for the beginning of that sort of post-indie music experimentation. FL