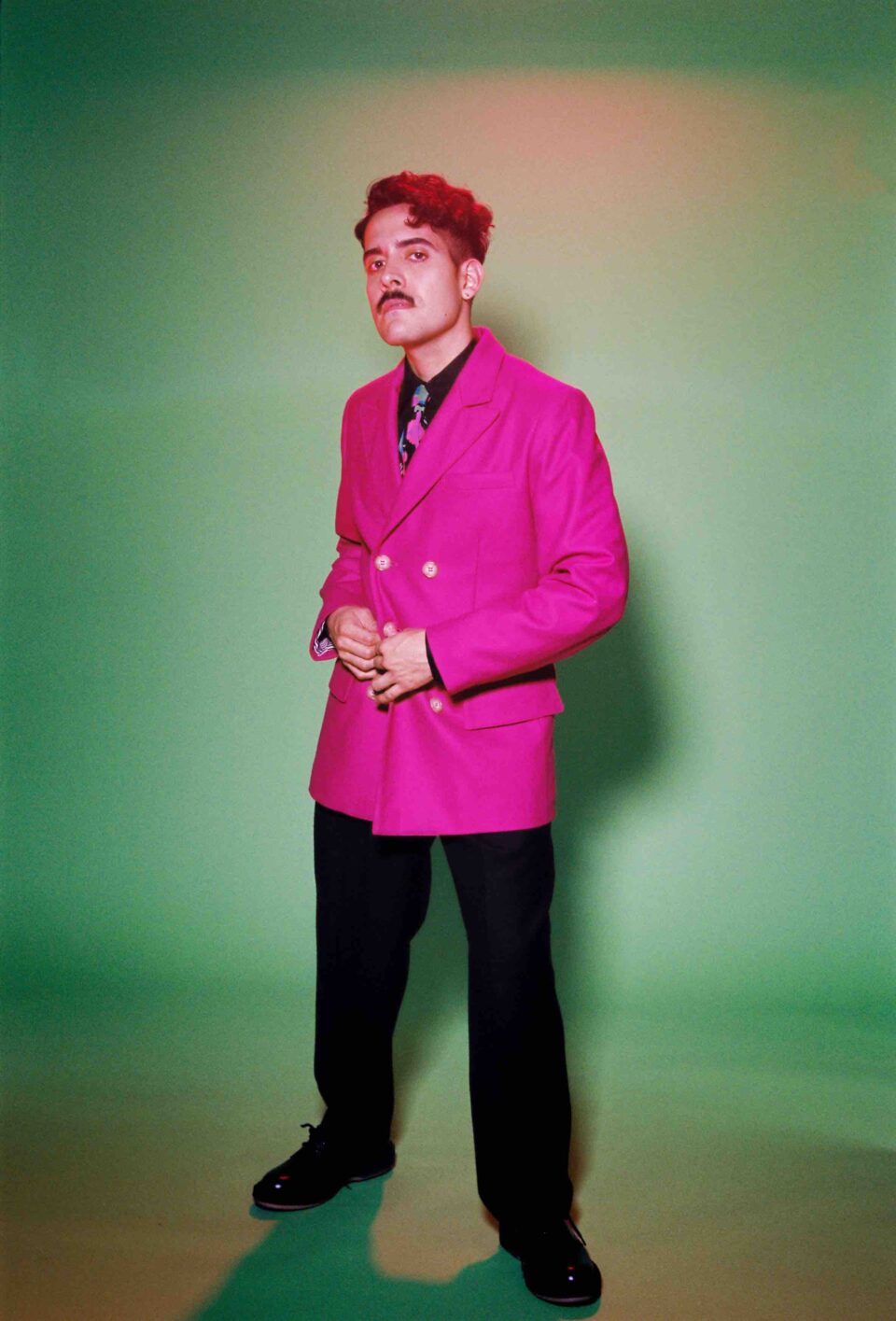

Back in 2016 or so, Alan Palomo began envisioning the next chapter in his career as songwriter and producer Neon Indian. He recruited his brother, who had begun playing in his live band on the tour supporting Palomo’s 2015 album VEGA INTL. Night School, and they embarked on making a cumbia record. He envisioned it as his version of The Wall—a direct response to the Trump era politics that were just beginning to infest this country. But Palomo learned rather quickly that he didn’t work well with such a direct prompt, and the idea slowly began to dissolve. Then, when COVID struck, Palomo took some more time to figure out his next steps—he bought a piano, learned to sight-read, and before he knew it he was approaching a decade without a new album to his name.

With World of Hassle, Palomo’s first release under his given name, he wanted to make an album that reflected the improvisatory spirit of his live show. Alongside his brother and two friends from Denton, Texas, Palomo had been moving his concerts into jazz-infused sophisto-pop territory. World of Hassle embraces this style wholeheartedly, creating a collection of sultry synth grooves and saxophone solos that are sweet without being saccharine. The album features contributions from Mac DeMarco and L’Impératrice vocalist Flore Benguigui, and was partially recorded in Daniel Lopatin (a.k.a. Oneohtrix Point Never)’s studio.

We sat down with Palomo to discuss the new record, releasing music in the streaming era, the influence of Thomas Pynchon, and more.

How did your time off help inform this new record?

Everyone had a project during COVID, and my mind was like, “Alright, I finally want to learn how to sight-read, so let’s start digging into that.” I wanted to bring more of a jazz influence into what I was writing. My brother joined my live band, and he went to Berklee, so I needed players who could speak his language but bring a different energy, too. I lucked out and I had these two friends from Denton. Suddenly we had this band of shredders, and on tour I’m improvising covers every night. It was cool because I’d never had that kind of freedom before. But the flip side of that was that I realized I was the least technically adept person in my band. I mean, obviously they couldn’t fire me because I write the songs, but it did light a little bit of a fire under my ass.

“I realized I was the least technically adept person in my band. I mean, obviously they couldn’t fire me because I write the songs, but it did light a little bit of a fire under my ass.”

How does that influence inform World of Hassle?

It’s such a tried-and-true, ’80s male rock cliché to suddenly have a crisis in your thirties and leave your band to write a jazz-influenced sophisti-pop record. That was the whole blueprint for it. Bryan Ferry is my favorite example of that. Once he found the Avalon formula, he just peaced out [left Roxy Music] and wrote more [solo music]. I was talking to Dan Lopatin about it because I was recording in his studio when I was really digging into the record, and he showed me this documentary from Sting called Bring on the Night. It was the same fucking thing: He suddenly decides The Police is over. He hires this DC jazz band and rents out a 17th century chateau outside of Paris just to rehearse, which is insane.

Since you don’t like writing to prompts, how did the thematic nature of this album unfold?

To clarify, I would say I don’t like writing under a very specific prompt. I think with the [aborted] record, it was to make a politically inclined psychedelic cumbia record that explores my brother and I’s origin story, but that was too specific. You’re not writing a screenplay, you’re writing a record. With this album, it starts to sprawl out a bit more like a novel where the thematic elements and aesthetics support these smaller, contained stories within it. My job is to figure out how all these pieces fit. The narrative doesn’t have to be as literal. When I hear people say “concept album,” it almost sounds like you’re making a musical or something, or it’s supposed to have this very linear experience.

“It’s such a tried-and-true, ’80s male rock cliche to suddenly have a crisis in your thirties and leave your band to write a jazz-influenced sophisti-pop record. That was the whole blueprint.”

In terms of concept, and in terms of why I had the name World of Hassle, it came from a Pynchon line—something like “Where it was unbeknownst to him, he was entering a world of hassle.” I like that his protagonists are always being fucked with by some external force that they can’t identify. They always feel like they’re the butt of some joke. Who didn’t feel that way during COVID? I hope that when people pick up the record, and they read the fictional articles within it, and the world-building aspect of this fictional publication of World of Hassle—I hope it all makes sense. It’s opposed to what you have to do now when you’re putting a record out, which is just keep giving them a taste of it, and then eventually they get the whole thing.

The streaming landscape has changed since you last released a record. How have you approached that unappealing side of the industry?

The struggle between editorial narrative and the casino of the algorithms is very difficult to square. It’s like the song that you might think is the single—where you pour all your resources into the music video or whatever—might not necessarily be what this fucking robot thinks is the right song. You’re in this bizarre stalemate where you’re trying to get enough momentum going to really command the narrative around it and really bring people into a world, as opposed to how I see a lot of records come out. We’ve had to do this as a slow, steady rollout, but this idea of cutting the record up into little pieces and then feeding it out like chum until you take the last bigger chunk and just be like, “Here it is,” goes against the very grain of why I make music. I make records. That’s, to me, an experiential thing. It’s what got me into music.

“This idea of cutting the record up into little pieces and then feeding it out like chum until you take the last bigger chunk and just be like, ‘Here it is,’ goes against the very grain of why I make music.”

I may be drawing a false parallel here, but is that why there’s been this long of a period between records for you? Have you been trying to reckon with how you want to make music in an inhospitable environment?

Not necessarily. In general, it takes a long time for me to just come up with ideas that I like and work through them. I wish I could be more prolific, and I have friends who are always putting something out. Call it perfectionism, call it delusion, but there’s just a need to sit for a second and really process through it and continue to tinker with it.

During COVID, I didn’t realize just how much the industry had changed until I actually started putting out a record. I was blissfully ignorant to the necessity of things like TikTok or playlist placement. I would joke with my manager that by the time I put this record out, it’s going to be the end of Interstellar—when I deliver it to the label, it’s like a whole new generation of people, and the head of the label has just become an AI representation of themselves. So I knew I was entering a different world, I guess I didn’t know how different it would be.

But at the same time, when you returned there was palpable excitement for your first album in almost eight years.

If I would’ve finished the other record, that would’ve been a little bit more reasonable. I don’t regret shelving that album for the time being, because if it’s not done, it’s not done. I’ve only ever put out one record under the gun, and if a song comes on at a cafe or something, or I stumble across it again, the same problem I had with the mix a decade ago is still the same problem I have with the mix now. If it’s out there for the rest of your life and you got to stand behind it, why not put a little love into it? FL