Forty years ago this past spring, the Los Angeles arts collective Desolation Center staged Mojave Exodus, a live music event featuring post-punk bands the Minutemen and Savage Republic, in a dry lake bed in California’s Lucerne Valley. The generator-powered pop-up concert in the middle of nowhere enabled attendees to enjoy the music and let their freak flags fly without fear of being clubbed and arrested by the LAPD, who—under the leadership of infamous police chief Daryl Gates—had declared war on LA’s various underground music scenes.

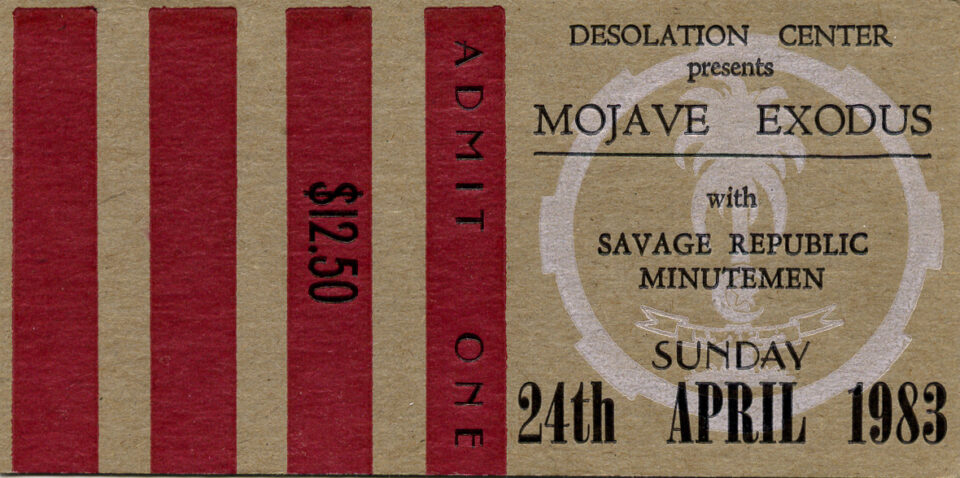

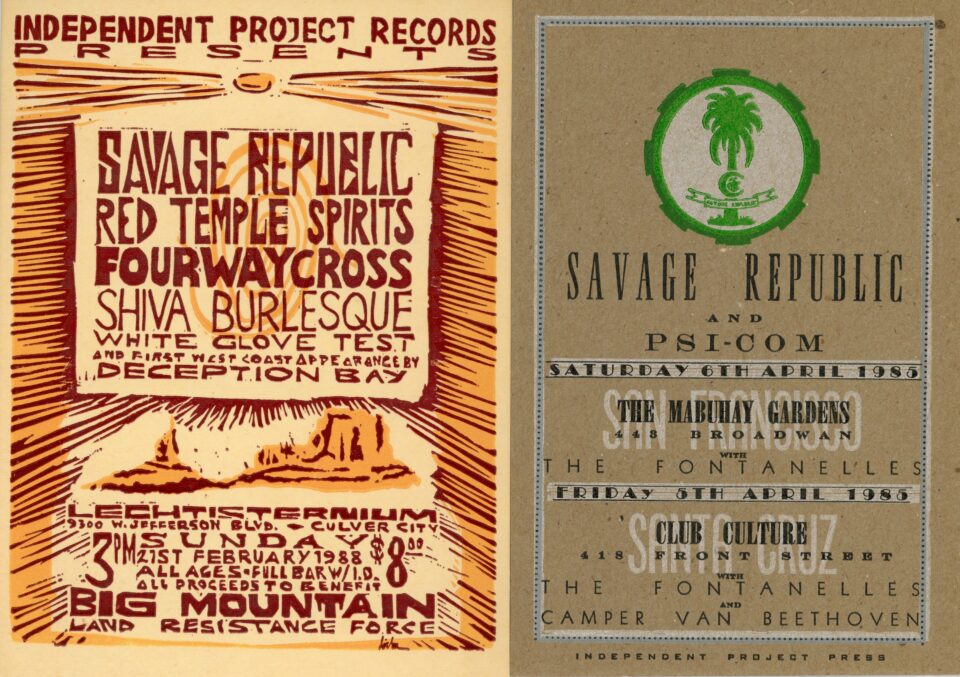

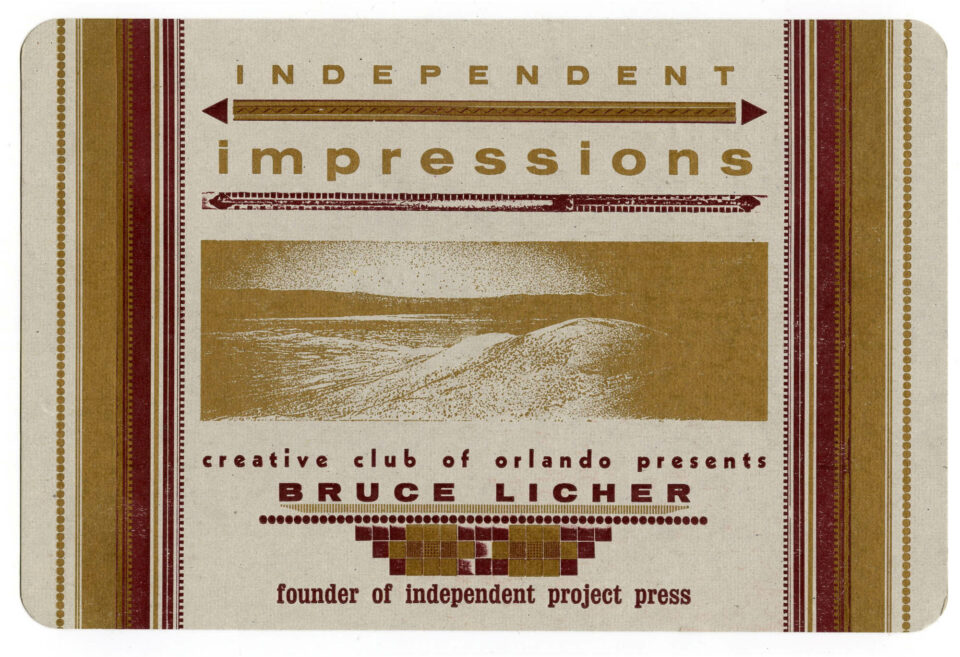

Tickets to Mojave Exodus cost $12.50, which got you a ride to and from the desert on a rickety bus, along with admission to the event—though it’s not like anyone was taking tickets at the door. And it’s not like you would’ve wanted to relinquish your ticket, anyway; strikingly printed in black, red, and white ink on brown chipboard, the event’s wonderfully tactile tickets—designed and hand-letterpressed by Savage Republic’s Bruce Licher—were works of art in and of themselves. “It was always very prestigious if Bruce would agree to print up your shindig,” recalled Perry Farrell in Desolation Center, the 2018 documentary about Mojave Exodus and Desolation Center’s subsequent guerrilla concerts, which eventually inspired the creation of such high-profile gatherings as Farrell’s Lollapalooza, Coachella, and Burning Man. “He was really good with the printing press. He was like the Benjamin Franklin of our scene!”

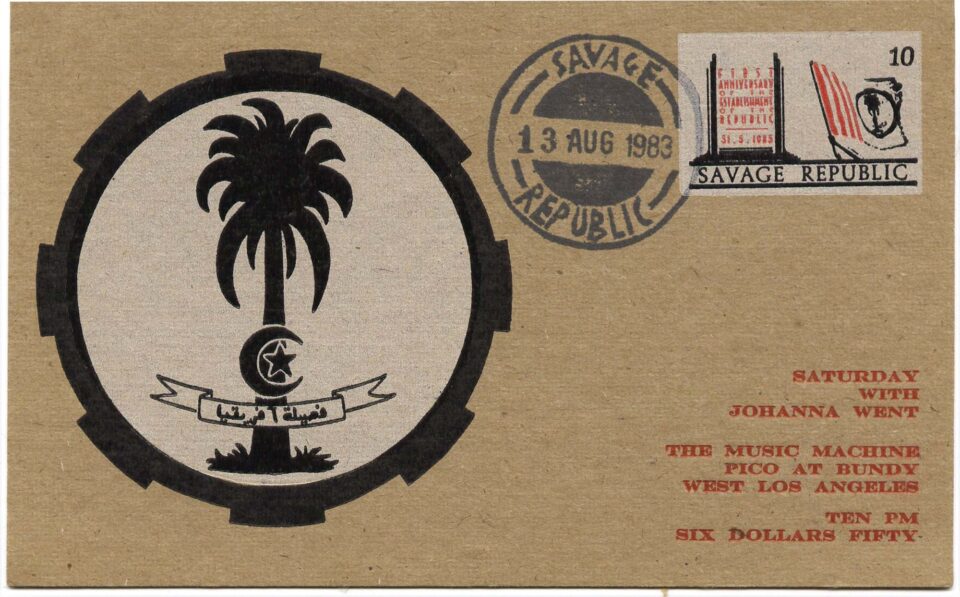

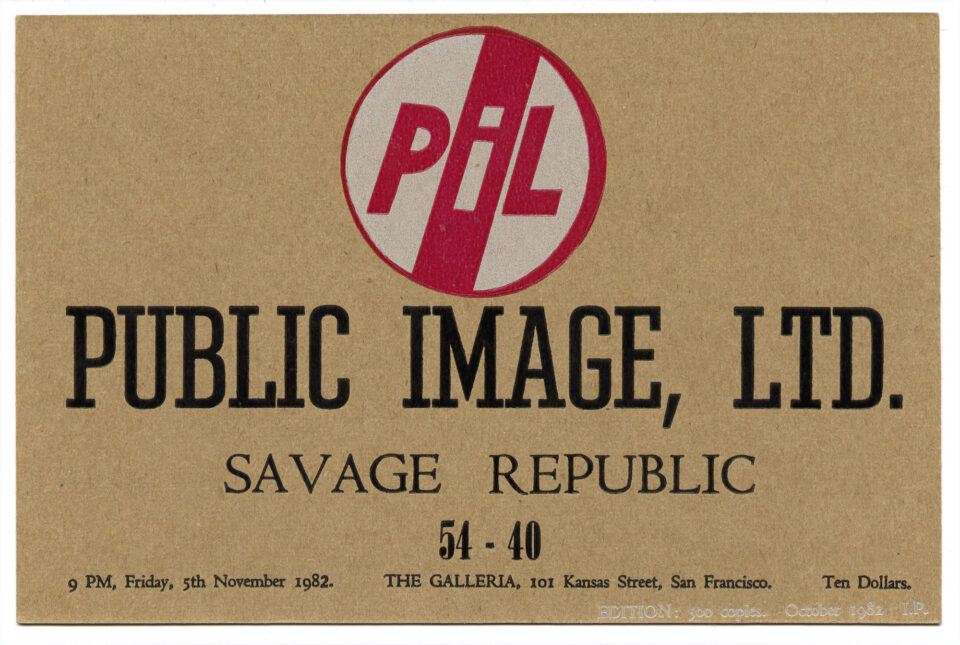

At a time when Xerox machines were practically synonymous with the DIY ethos, Licher’s lovingly artisanal approach extended not only to the creation of hand-letterpressed posters and tickets for various local shows, but also to the design and production of artwork for the records released on his Independent Project Records and Nate Starkman & Son imprints—even right down to the labels’ paperwork. “I remember when we got our contracts from Bruce,” laughs Jeffrey Clark, whose band Shiva Burlesque released their self-titled 1987 debut on the latter label. “[Bandmate Grant Lee Phillips] was like, ‘Wow, this is like the most beautiful-looking contract for a record release I’ve ever seen in my life!’”

“The whole idea of the label from the beginning was, ‘Let’s make records as fine art.’” — Bruce Licher

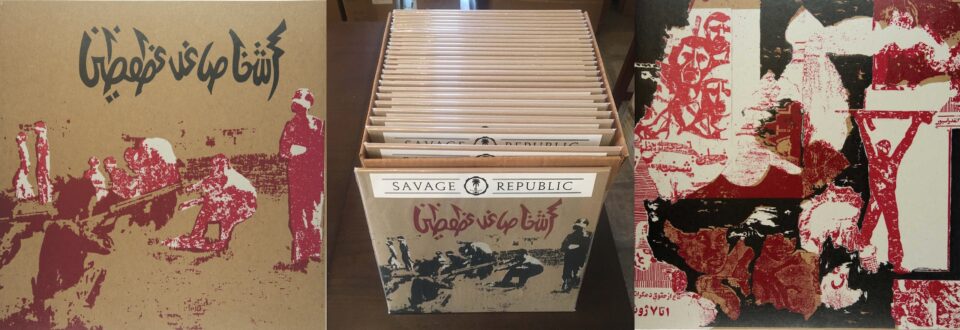

“The whole idea of the label from the beginning was, ‘Let’s make records as fine art,’” says Licher of Independent Project, which he originally launched in 1980, and which was rebooted in partnership with Clark in 2020 after a semi-hiatus of nearly two decades. “The first three 7-inches I put out on IPR [releases by Project 197, Bridge, and Them Rhythm Ants], I was trying to do something different and creative with each of those in terms of silk-screening the packaging. But I don’t know that I necessarily succeeded greatly until I ran across the letterpress. That was when the ah-ha moment came.”

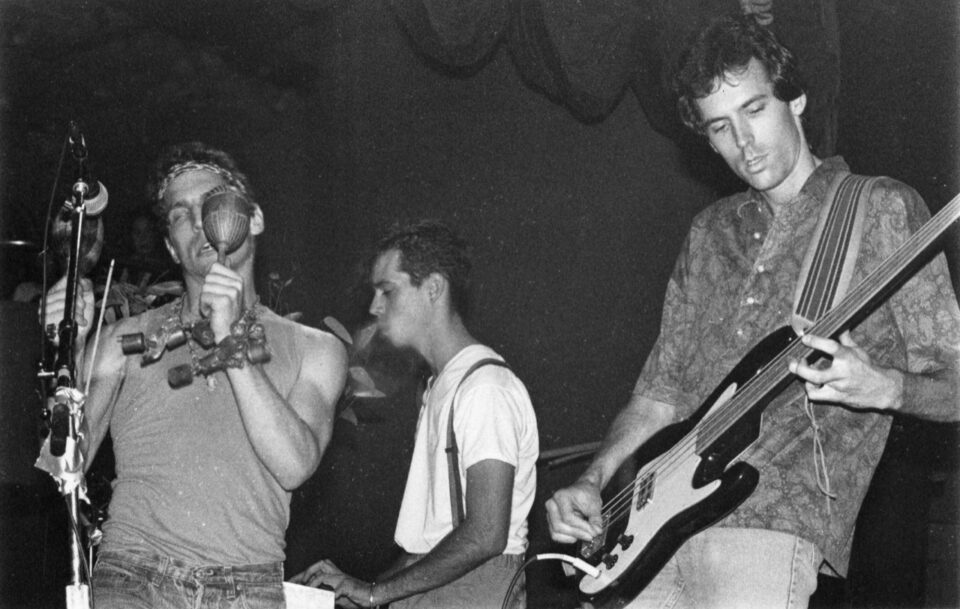

Savage Republic / photo by Annabelle-Port

Licher discovered letterpress technology while he was a student at UCLA, around the same time that his band Africa Corps—which would soon be renamed Savage Republic—was getting off the ground. “I was just looking for an artistic way to make a record album jacket, so I signed up for a class in offset lithography, because I thought maybe I could print my album cover in that class,” he explains. “The class got canceled, but the teacher said, ‘Well, we have this letterpress class that we’re teaching next week. You could sign up for that.’ I’m like, ‘Oh, OK.’ But I had no idea what letterpress was. So I took the class, and the project was to make a postcard. So I made a postcard advertising the forthcoming album by Africa Corps.

“It was always very prestigious if Bruce would agree to print up your shindig. He was really good with the printing press. He was like the Benjamin Franklin of our scene!” — Perry Farrell in the 2018 doc ”Desolation Center“

“And while I was there working on that,” he continues, “I saw this other big flatbed press with an 18- by 24-inch bed that nobody was using. I kept thinking, ‘That’s the perfect size for an album jacket!’ The teacher said, ‘If you take the class again, I’ll teach you how to use that press. Nobody uses it because they’re kind of afraid of it!’ So I took the class a second time and bought a thousand sheets of chipboard, and I made an album jacket for Tragic Figures, Savage Republic’s first album. And then, once I'd done that, I was like, ‘Oh, this is it!’”

Licher’s intuitive and deeply personal approach to graphic design has always informed his music, as well. “I'm basically a self-taught musician, and here I am 40-some years later and I couldn’t tell you what notes or chords I’m playing,” he laughs. “I mean, the instrument that I play is an electric 12-string guitar with 10 strings on it, and six of them are tuned to the same note. I just want something that creates beautiful sounds to me, so I find things on this structure of an instrument that has sort of evolved over several decades, and find ways to put them together and into pieces of music that are pleasing to me.”

“The thing about Bruce that you really get once you’re around him a little bit is that he just has integrity as a person,” says Clark. “Bruce is a serious person. He takes what he does seriously, and you always know you’re dealing with somebody who’s motivated by creativity and art.”

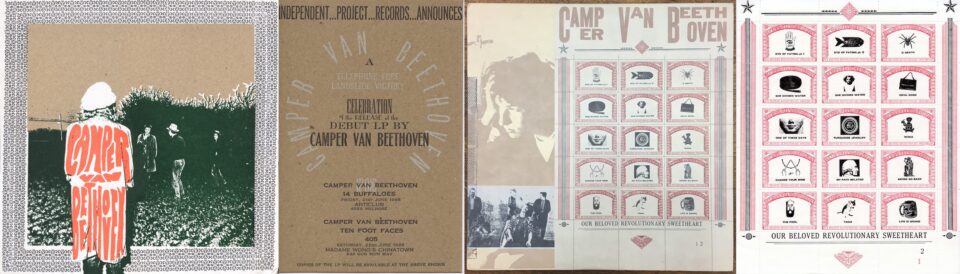

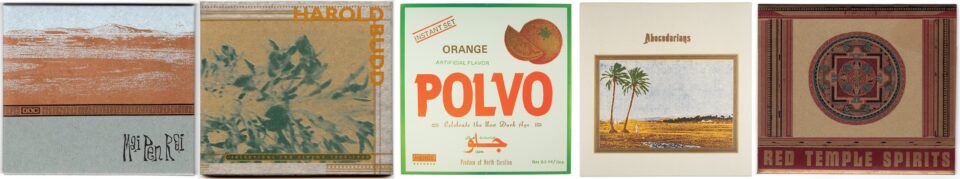

Released in 1982, Tragic Figures set the tone for all IPR releases to come. Though the music of bands like Camper Van Beethoven (whose debut Telephone Free Landslide Victory was released on IPR in 1985, complete with Licher’s letterpressed packaging) didn’t necessarily resemble Savage Republic’s intriguing mixture of Branca-esque guitar noise and Middle Eastern soundscapes, Licher consistently gravitated toward artists who defied easy classification and thus had difficulty attracting the attention of larger labels. “The thing I always did with IPR from the beginning is think, ‘What music is out there that I would want to have a record in my collection?’ It was like, ‘Hey, this is great music and nobody else is putting it out, so I should do it.’”

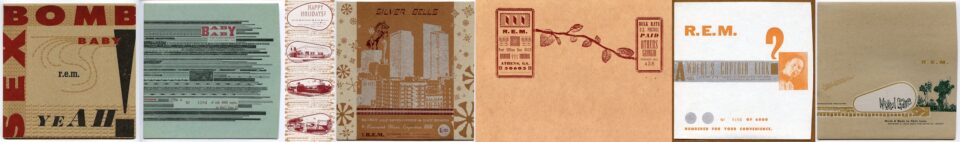

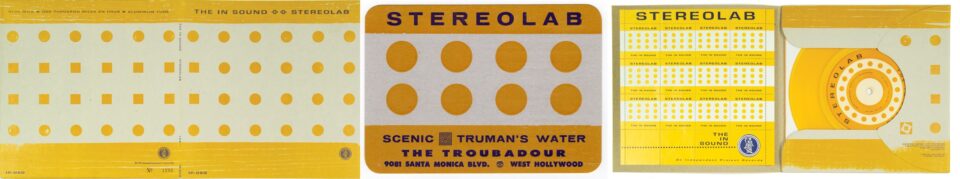

Camper Van Beethoven’s success—not to mention Licher’s Best Album Package GRAMMY nominations for For Against’s 1987 IPR debut Echelons and Camper’s 1988 major-label debut Our Beloved Revolutionary Sweetheart—drew industry attention to Licher’s striking graphic design work, leading to designing and packaging assignments for such high-profile acts as R.E.M., Scritti Politti, Stereolab, and Silversun Pickups. (A limited-edition 2020 monograph from P22 Publications documenting 40 years of Licher’s influential work includes 14 pages devoted to his packages for R.E.M.’s holiday fan club singles.)

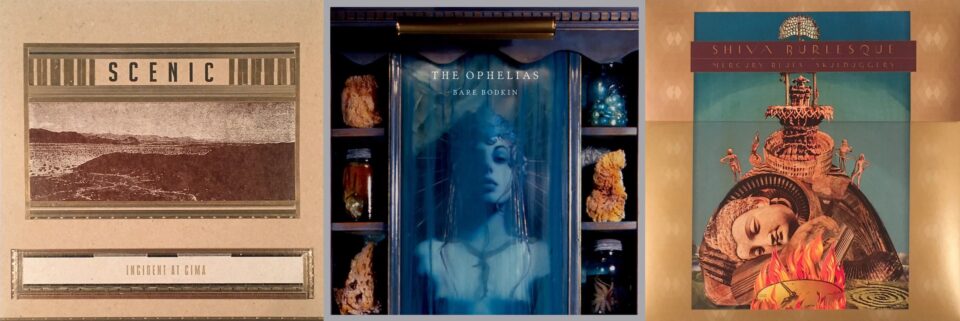

Licher didn’t let his freelance design gigs get in the way of IPR’s mission, however; from 1982 to 1996, the label averaged over four new releases a year, putting out records in various formats by such disparate bands as The Dentists, Half String, and Alison’s Halo. IPR also released several brilliant records by Licher’s own band Scenic, whose trippy, desert-baked sonic journeys reflected his move from Los Angeles to Sedona, Arizona (he’s since relocated, along with all IPR operations, to Bishop, California). But in the late ’90s, IPR’s output slowed significantly. “It wasn’t officially shuttered, but it just wasn’t making me a living,” Licher explains. “I just needed to focus on my printing and design business. So there were really only a few releases between, say, 2001 and 2020, until we relaunched it.”

Scenic (Bruce Licher’s post-Savage Republic band) in Las Vegas / photo by Checko Salgado

IPR’s relaunch, poetically enough, came via the release of the Desolation Center documentary. Clark, now the program director of the Nevada City Film Festival, screened the film for the 2019 festival and invited Licher to appear for a post-film Q&A. And from there, the wheels started turning. “I’d worked with Bruce on my solo album, Sheer Golden Hooks, and I loved collaborating with him on that,” Clark recalls. “Then in the ’90s I moved from Los Angeles and so did Bruce. We’d kept in touch every once in a while, but really I hadn't seen him for a number of years. When he came up for the film festival, he stayed at my house in Nevada City, and we just were kinda chatting and catching up on stuff.

“I was very inspired by the film, by the kind of retrospective that it gives to that whole scene; I’d also been noticing how vinyl was kind of making a comeback, and how a lot of the younger people I interact with in Nevada City were very interested in the aesthetic of music from the ’80s and early ’90s, kind of post-punk up to shoegaze-era. And so I just started thinking, ‘Maybe it would be a viable thing, or certainly be a cool thing to do, if the label could kind of get back into creating records again.’”

“The thing I always did with IPR from the beginning is think, ‘What music is out there that I would want to have a record in my collection?’” — Bruce Licher

Since IPR’s visual and sonic aesthetic has always directly emanated from Licher, he’d been understandably leery about partnering with other people or labels in the past—but he feels that Clark is the perfect collaborator for IPR’s revived incarnation. “For many years, I wasn’t sure how or if that would ever work,” he says. “I’ve always wanted to be able to do more than I was able to with the label, but I just didn't have the finances or the wherewithal to do that. And you start wondering, ‘OK, if you get a distribution deal or a bigger label willing to fund you, are you gonna end up losing some of your control?’ But the more Jeff and I talked about it, I got the feeling that he shared most of the same ideas of what I considered important about the music.”

While the bulk of IPR’s releases since 2020 have been devoted to sumptuously packaged reissues and archival releases of recordings by Savage Republic, Scenic, Half String, The Ophelias, and A Produce—including the recent expanded limited-edition reissue of the latter’s 1994 new age/ambient classic Land of a Thousand Trances—the label is also releasing new projects like Mutant Gifts, a 2022 EP by dancer, choreographer, and musician Alison Clancy. “Jeff is bringing in things that I wouldn’t necessarily think of myself for the label,” says Licher. “Alison Clancy is someone who I think fits in perfectly with our aesthetic, but I wouldn’t have known about her if it hadn’t been for Jeff.”

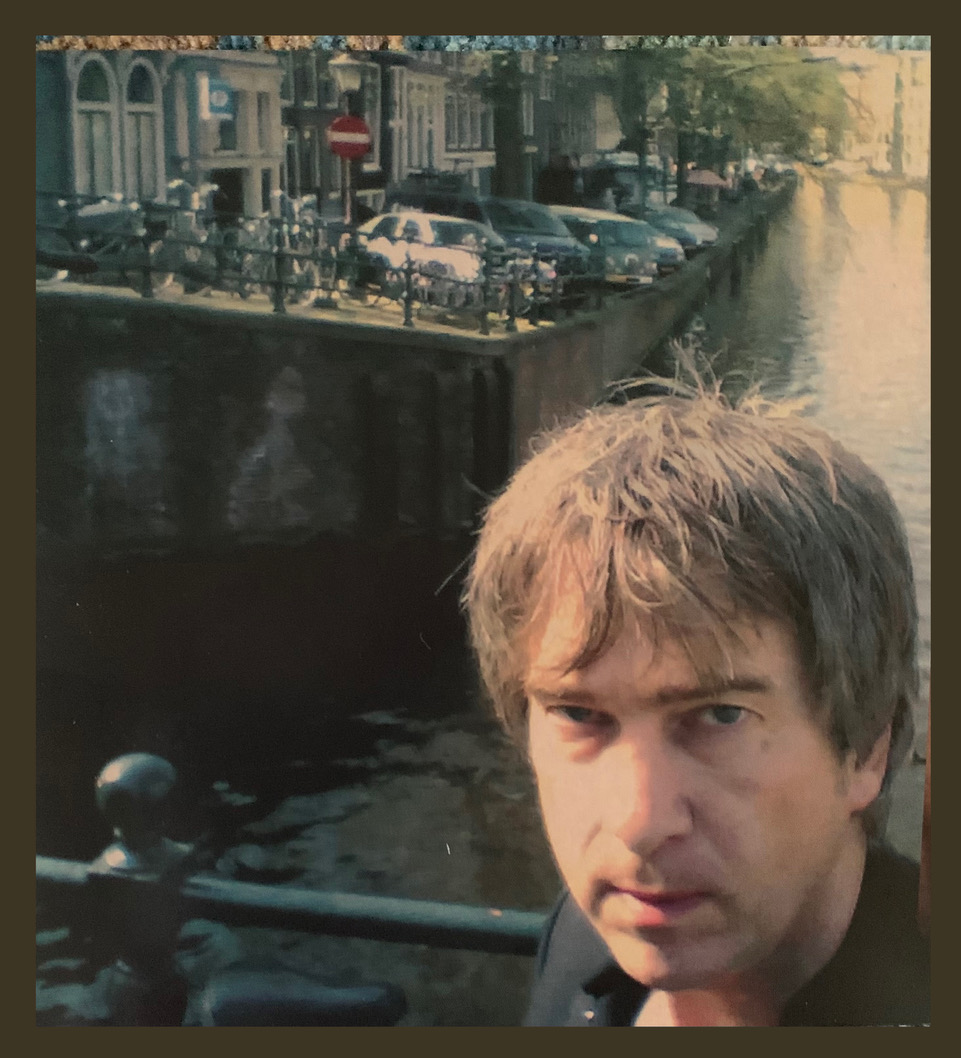

Jeffrey Clark

“I hear that a lot of people collect vinyl but don’t play it. So if that’s the case, then boy we fill that need, because there’s nothing like these releases that IPR has done and is doing.” — Jeffrey Clark

All new IPR titles are being released on CD and vinyl, with both formats featuring Licher’s gorgeous letterpress designs and industrial-grade chipboard packaging. “You can download the music as well,” says Clark, “but an IPR release is a work of art, a special object. I hear that a lot of people collect vinyl but don’t play it. So if that’s the case,” he laughs, “then boy we fill that need, because there’s nothing like these releases that IPR has done and is doing.”

Of course, basing your label’s visual aesthetic around technology that was already considered “outdated” decades ago is not without its challenges. “The most interesting paper stocks always get discontinued,” Licher laughs. “The photo-engraved printing plates that we’re doing now, almost everybody who makes these plates does it from a computer system instead of taking art and photographing it and creating the negatives. And there are certain techniques I used to do back in the ’80s that literally cannot be done now, because almost all of the photocopy machines are digital, and of course most photography is digital now too.

“What so often happens is that when technology moves forward, the older technology falls away,” he continues. “And sometimes I just wish that the older technology didn’t have to fall away because, you know, why not have the old technology and the new technology? In a way, that’s what we’re doing; that’s why I think it’s so great to still have the letter presses here. When I was working in Downtown LA back in the ’80s, the most expensive piece of equipment I had was my photocopy machine. It was a beautiful Minolta with two different colors of toner in it; you could put both black and either red or sepia or whatever, and I did a lot of inserts and mailers and things like that with this two-color photocopy machine.

“But by the early 21st century, nobody was repairing or servicing them, and I couldn’t get parts. And when I moved out of Sedona, I literally took this thing that was the most expensive piece of equipment in my shop, and I left it at the dump. I wish I still had it. I wish it still worked. But you’ve gotta move on, I guess.” FL