Starting in the late 1970s and continuing well into the 1980s, The Police had an extraordinary run of hits: “Roxanne,” “Message in a Bottle,” “Every Breath You Take,” and so many more. As their drummer, Stewart Copeland’s signature sound was one of the band’s most defining elements. But Copeland almost walked away from the group before this streak began. An American expat living in London, he’d started out working with the prog band Curved Air, then co-founded The Police in 1977 with Sting—but he was still ambitious enough to keep writing material on his own.

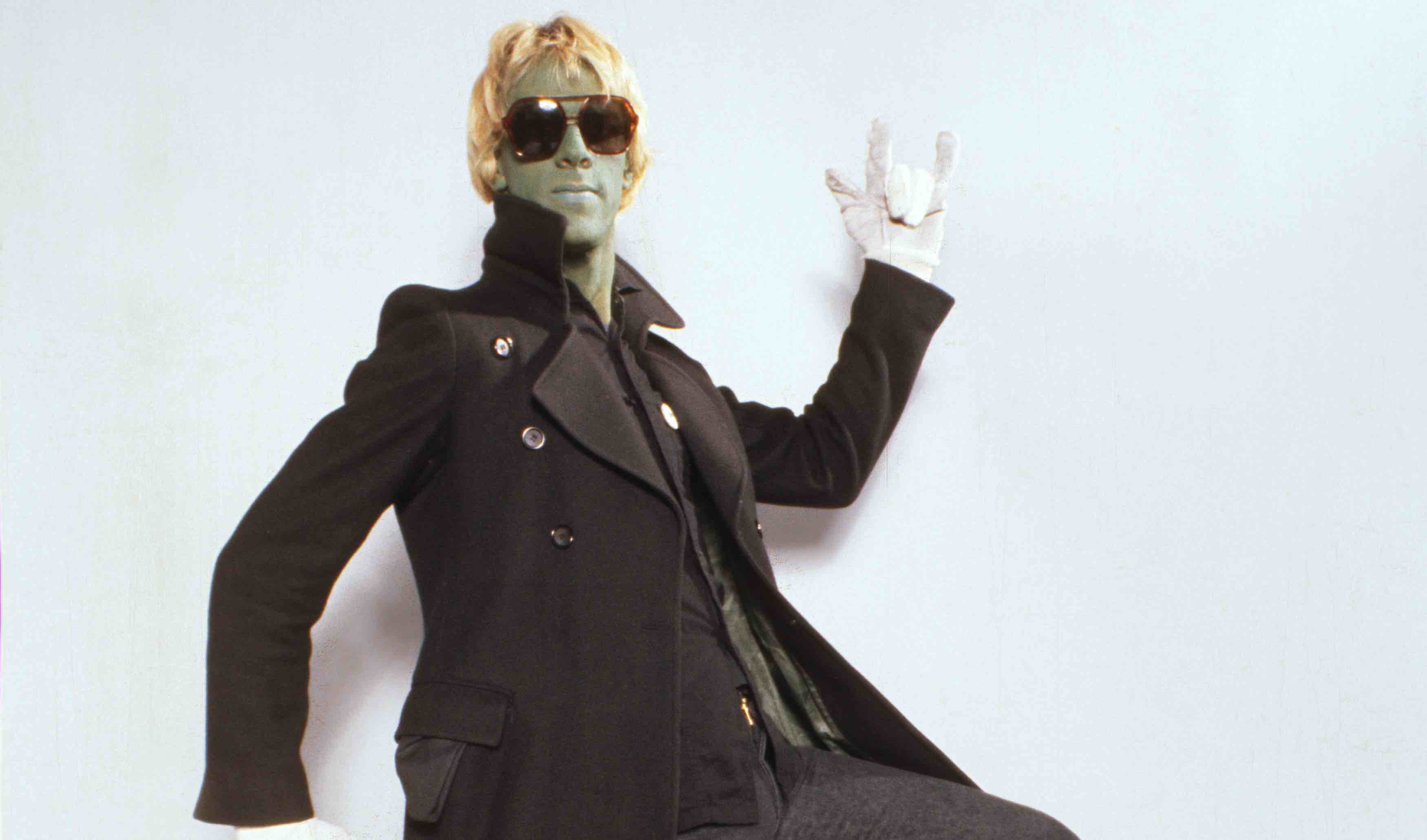

In 1978, he released the single “Don’t Care” under the pseudonym Klark Kent. He sang and performed all the instruments for the track, which ended up reaching #48 on the UK charts. This encouraged Copeland to continue writing and recording, resulting in the 1980 album Klark Kent and the temptation to focus exclusively on his solo career. In the end, Copeland decided to throw his lot in with The Police, so there were no further Klark Kent albums. But his auspicious solo debut is now getting the deluxe reissue treatment featuring previously unreleased songs—including all of the home demos Copeland recorded for each song on the original album.

After The Police initially disbanded in 1986, Copeland shifted his focus to composing for films and television soundtracks (he began in 1983 with his experimental score for Francis Ford Coppola’s Rumble Fish), and then operas and video games. With its glimpses into some of his earliest work as a songwriter and recording artist, this Klark Kent reissue reveals a groundbreaking musician on the brink of conquering the world.

Did revisiting this project bring back any particular memories for you?

For two years, [The Police] starved before we started to get anywhere. And Klark Kent actually did have a hit during that period. The first time [our] three blonde heads were on national TV was as Klark Kent’s band, even though it was a solo album. But when BBC Radio 1 picked it up and put it on their playlist, I started moving up the charts [with “Don’t Care”], and I got that spot on Top of the Pops. But I didn’t want to appear just as a guy standing there, so I got my buddies to be in my band. We’re all in masks. I think it’s Sting in a gorilla mask and Andy [Summers, guitarist] in a Brezhnev mask. But that’s my big brag, that our first shot on national TV was as my backing band. It’s on YouTube—you can spot Sting and Andy right away.

Why did you do this using a pseudonym instead of releasing under your own name?

Because my name was mud at the time. The Police had been exposed by British critics as a band of carpetbaggers—which was true. The Police was dead in the water, uncool, unloved. And so I thought, “Well, why don’t I do it with a secret identity?” Every interview I did, I came up with different stories about this character. It didn’t last. NME busted me at some point, but it was just a fun way to do it. For 20 seconds, the zeitgeist in London was asking, “Who is Klark Kent?” That made it a lot of fun.

“If I’d said, ‘Sorry, guys, I’m out of here—I’m doing my own thing,’ that would’ve been a bad move. Fortunately, The Police rose up in the nick of time.”

With hindsight, do you notice any themes that you were trying to get across when you wrote these songs?

I guess the angst of young adulthood has its tensions, and that’s the struggle period. “Desperate to succeed,” that’s the vibe. In my diary, January 1, 1978, [I wrote], “I’ve got 138 quid in the bank, and 40 of it is owed for rent, something or other is owed for something else, that leaves me £7.48 until my next lucky break.” And as I’m having my personal first hit, I was evicted from my apartment because I couldn’t pay the rent. So it was the bottom and the top at the same time. During those years when we were starving and I was doing Klark Kent, none of us had heard “Roxanne” or “Message in a Bottle” or “Every Breath You Take” because Sting hadn’t written them yet. He didn’t write any of those great songs until a year and a half into the band’s existence. Before that, we just had my crap punk songs, which were basically basslines with yelling—which was all that was required from the scene.

Did you ever think, “This is going pretty well and the band thing isn’t, so I should just continue as this solo artist”?

Absolutely, and it’s in the diaries. I would just write furiously in there as a kind of personal therapy, and they were not to be seen by anybody—except, 50 years later, they come off as comedic to me, and so they’re in my book. But yes, that very thought that you expressed was in there: “I don’t need these guys. I’m having a hit on my own!” Fortunately, Klark Kent disappeared without a trace, and just in time for The Police to demolish everything in its path. I mean, if I’d said, “Sorry, guys, I’m out of here—I’m doing my own thing,” that would’ve been a bad move. Fortunately, The Police rose up in the nick of time.

“I was a little pipsqueak until I banged on a drum. Then, suddenly, I became an 800 pound silverback gorilla swinging through the trees.”

How did you know you should be a musician in the first place? Especially because, as you pointed out, it can be a very precarious career.

Parents are telling me, “I’ve got Emily taking piano lessons.” I say to them that if you have to say, “Emily, I think it’s time for your practice now”—forget it, it’s over. If you have to say, “Emily, would you please shut up for a minute?”—OK, now you know you’ve got a musician in the family. It’s because you can’t do anything else. In fact, I did many other things. I was a journalist, I was a radio jockey, I was a roadie, tour manager, all these things. But I just found myself in the band. There was no escaping it.

How did you come up with your distinctive drumming style?

Not through any conscious design, but by an accident of birth. I was born into a diplomatic family, which meant that my early years were in Cairo and Beirut, Lebanon, and I was surrounded by Arabic culture. And even though I was thirsting for Rolling Stones and The Kinks off the one hour a week of Voice of America radio playing pop music, Arabic music got into my DNA. And, by coincidence, Arabic music has a rhythm that shares some fundamentals with reggae, which is an emphasis on the third beat of the bar and hiding beat one of the bar. So as an adult, when I got a whiff of that reggae thing, I could do it really easily.

When did you realize you had a gift not just for music?

I was a late developer, a wimp, a runt of the litter, and at age 12 all my friends were starting to shave and grow up. I was a little pipsqueak until I banged on a drum. Then, suddenly, I became an 800 pound silverback gorilla swinging through the trees. Playing at my first show at the British Embassy Beach Club in Beirut, I’m playing [The Animals’] “We’ve Gotta Get Out of This Place,” and right there in front of me is Janet McRobbins, fully 15 years old. For a 12 year old, to be moving the body of a 15-year-old girl was beyond empowering.

Do you ever feel under pressure to live up to people’s high expectations now?

Yes, I do. Not when I walk onstage, but when I’m not onstage and I’m out of shape and I’m just picking my nose and someone says, “I’ve got a drum set here, you wanna play?” No, I don’t. But when everything’s right, when I’m rehearsed, when I’m in good shape, when it’s a show, I walk out there, and I love it. FL