Whether through being put on a pedestal or denounced as bad influences, female rock musicians have always had to cope with pressures their male peers never get confronted with—constantly forced to choose between staying true to their own vision or compromising in the face of unrealistic expectations. Time and again, women in rock have risen to the challenge, serving as proponents of progress while increasingly taking control of their music, message, and public image. In this way, they’ve made revolutionary contributions to the successive waves of feminist activism dating back to the 1960s.

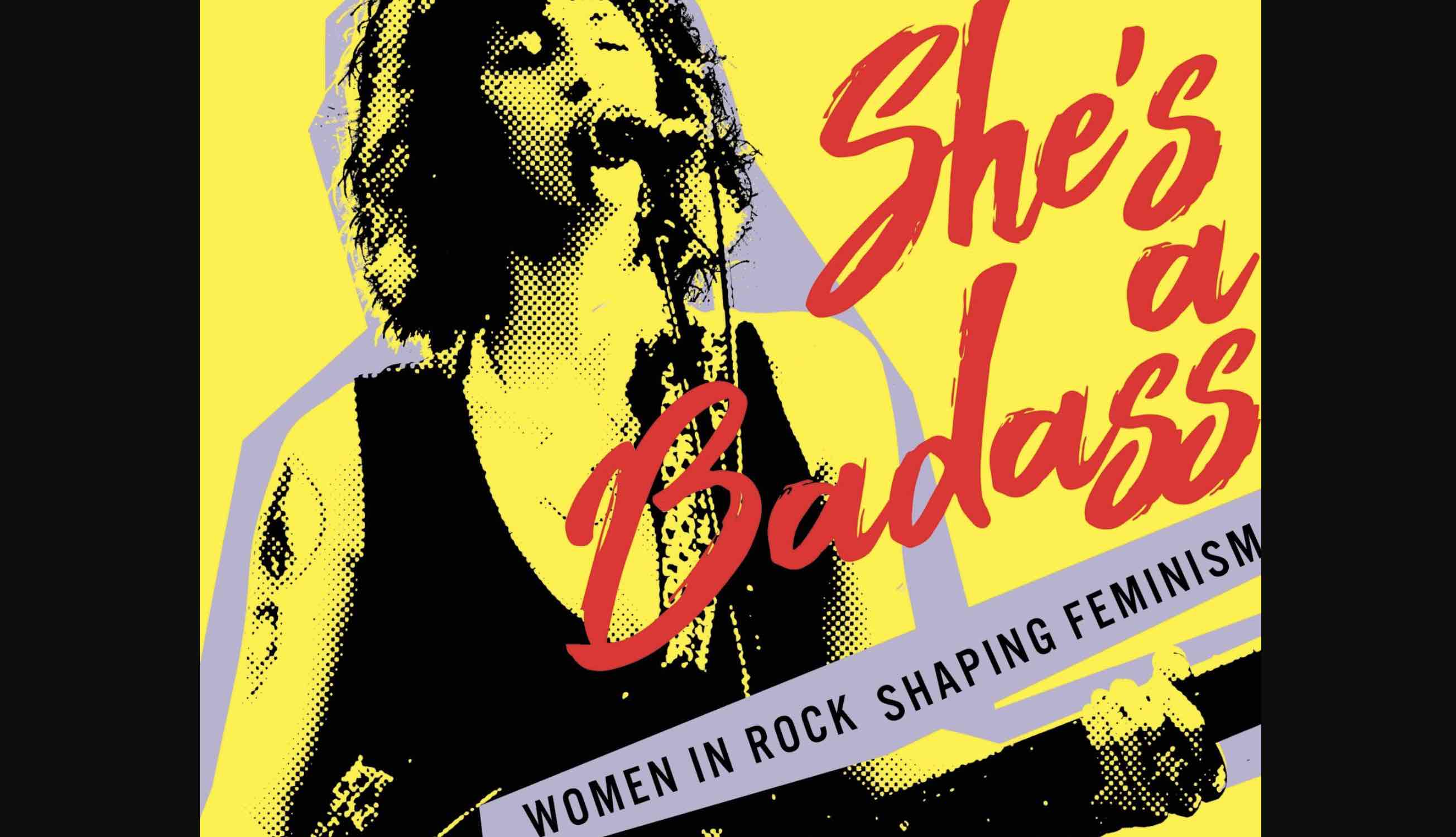

In She’s a Badass: Women in Rock Shaping Feminism, music journalist (and FLOOD contributor) Katherine Yeske Taylor interviews 20 significant female rockers, taking an in-depth look at the incredible talent, determination, and, often, humor they’ve needed to succeed in their careers. Their experiences reveal the varied and unique challenges women in rock have faced over the years, how they overcame them, and what they think still needs to be done to continue making progress on the equality front. Their stories prove that promoting feminism, via conscious activism or merely by living example, is undeniably badass.

Featuring interviews with Suzi Quatro, X’s Exene Cervenka, Suzanne Vega, L7’s Donita Sparks, Laura Veirs, Death Valley Girls’ Bonnie Bloomgarden, Fefe Dobson, and others, the book lands on shelves next week. In the meantime, we have an exclusive look at three of the book’s chapters, featuring interviews with Tanya Donelly, Amanda Palmer, and Lydia Lunch. Check them out below, and pre-order the book here.

TANYA DONELLY (CHAPTER 11)

The first time Tanya Donelly encountered what seemed like blatant sexism, she reacted with disbelief. It happened as her alternative rock band, Belly, were riding high with their 1993 single, “Feed the Tree,” which had reached the top of Billboard’s “US Alternative Airplay” list and charted in the United Kingdom and Australia.

“I was doing a photoshoot for the cover of a magazine, and the publisher showed up and asked if I was free for dinner. I said yes. I brought my A&R woman and my manager with me. The publisher was visibly disappointed that they showed up with me, and then through the course of the dinner, it became pretty clear that he had thought that this was a date.” She politely deflected his advances. Then, “Within forty-eight hours, we were told that Belly wasn’t getting the cover.”

Even though, with hindsight, it’s obvious to her that he was punishing her for rejecting his romantic interest, “I immediately thought, ‘It’s not possible that that’s the reason we lost the cover.’ Now, with the distance of time, who fucking cares? But at the time, it was something that bummed the people around me out. The people who had worked for that moment, like our PR woman.”

Donelly stresses that she didn’t respond this way because she was naive (“Because I really was not naive ever in my life, really”)—rather, it was “because I had never experienced anything like that so overtly. I never blamed myself for a second. I went to a much weirder place, which was, ‘This has not been my life experience, so this cannot possibly be the cause of that.’” But another incident in the 1990s made it even more evident that women were not always being treated fairly in the music business. She recalls “sitting in a program director’s office and having him say to me, as if this were completely understandable, ‘Well, we can’t pitch your single to radio because there are too many women on the radio right now.’ And I remember being like, ‘What?’

“Just to give you an idea of how bone-level this kind of systemic thinking was at the time, he wasn’t even being a dick about it. It was just like we were comrades in the same battle, and I should understand that this was part of the war, basically:

‘Well, you understand. There are too many women right now, so we just have to wait a few months.’”

This time, Donelly wasn’t in denial. Instead, she objected immediately. “I said, ‘That seems ridiculous to me.’ Later on, when my manager and I were talking about it, I said, ‘Is it just that people can’t hear one woman’s voice after they’ve just heard another woman’s voice? Like, what does that mean?’” Considering that radio playlists have always consisted of consecutive male artists’ songs, the double standard was glaring. “I couldn’t believe it. Obviously, we pushed back, and had multiple written and spoken exchanges around that conversation.”

All that protest came to nothing, though. “At the end of the day, the argument was, ‘Hey, this is out of my hands; this is what I’m getting from radio.’” And, she adds, “Let me be clear: this included college radio, too.”

That last part was particularly galling, because in the 1990s, college radio stations were believed to be far more broadminded than commercial outlets. College radio was also the arbiter of taste for modern rock—and within that genre, few artists have been as accomplished and influential as Tanya Donelly.

She cofounded three of the most admired alternative rock bands: Throwing Muses, the Breeders, and Belly. Her work has twice been nominated for Grammy awards. As a solo artist, she’s put out more than a dozen releases. She’s also collaborated with a long list of well-regarded musicians, including Juliana Hatfield, Catherine Wheel, and Mission of Burma.

So, as a woman who has experienced intractable disrespect because of her gender despite achieving such success, Donelly knows that more progress still must be made—and that is exactly why she identifies as a feminist. “The only thing I dislike about that label is that it’s unfairly charged with negativity,” she says. “But in the name of every woman that came before me and worked under horrible conditions to move that feminism forward, I will never throw that label away easily.”

AMANDA PALMER (CHAPTER 16)

Buoyed by the Dresden Dolls’ success, Palmer felt confident enough to strike out on her own. She released her debut solo album, Who Killed Amanda Palmer, in 2008. Her 2012 follow-up, Theatre Is Evil, reached the Top 10 on the US “Billboard 200” album chart.

During this time, her personal life was also evolving. In 2011, she married famed novelist Neil Gaiman. That raised her profile—but this experience could be unpleasant. “One of the things that I took away from my relationship with Neil was just how deeply sexist the world is—and Neil would be the first one to point it out,” she says. “Neil and I could literally say and do the same thing, and I would be painted as the hysterical, crazy woman, and he would be painted as the delightful genius.

“Even though my career and my success way predated my relationship with Neil, I would see, and Neil would see, people on the internet saying, ‘Of course Neil Gaiman must have done that for her.’ Including the book that I wrote that became a bestseller,” she says, referencing The Art of Asking: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Let People Help (2015), which marked her debut as an author. “Oh, it was so infuriating.”

On the other hand, Palmer can see why she and Gaiman spark such differing responses. “Neil is a much more private person than I am,” she says. “He does not blog about his trauma, his experiences, his childhood, his feelings, his relationships. And I do. And people find it very threatening. They always have. From the early days of my blog in 2001, I encountered a lot of hostility, just because I was a woman chatting about my feelings. There are times when I am very tempted to say, ‘Man, I wish I could go back thirty years and make it all fictional. People wouldn’t have yelled at me if I had just written fiction.’

“And yet, I wouldn’t change a thing, because I know that I did it because I needed to do it. And I know that I’ve passed that torch on to [the next] generation of women who are going to be a little less afraid to speak the truth in their art.”

LYDIA LUNCH (CHAPTER 5)

In her immaculate and cheerful Brooklyn kitchen, Lydia Lunch has prepared a feast from scratch: Moroccan-style lemon chicken, spinach pie, ginger tea, and brownies. “Cooking—knives, fire, my DNA going into people’s mouths. What’s not to love?” she quips with a sly grin.

She may be most famous as a performer, but she also authored a cookbook in 2012, The Need to Feed: Recipes for Developing a Healthy Obsession for Deeply Satisfying Foods. Even the stage name “Lunch” (she was born Lydia Koch) is a reference to her ability, in 1970s New York City, to ensure that she and her friends were well fed during what would’ve otherwise been their “starving artist” days.

But make no mistake: beyond her stellar culinary skills, Lunch definitely isn’t the typical domestic type. Her all-black attire—lacy dress, fishnet stockings, and stiletto heels, along with perfectly applied dramatic makeup—makes her seem more ready to head onstage than to sit down for an interview in her living room.

Settling into an armchair, she veers between kind offers to refill a glass or plate and acerbic answers on a variety of subjects. The first topic in her crosshairs is the women’s liberation movement, which she dismisses. “We need a human liberation,” she says. “Right now, it feels like we’re in a backward cycle of everything. It just feels so ridiculous and outdated in this country. I find it outlandish that we’re still dealing with the abortion issue. I mean, we have the right to vote. Amen. But women had the right to control our bodies, and now we don’t in half the states? What the fuck?”

Despite her anger over US abortion laws, Lunch resists being called a feminist, however. “I have always tried to avoid any category,” she says firmly. But, she will concede, “I think I’m a humanist, in the sense that I think both genders—and now there’s many genders—are fucked by the powers-that-be. I feel that the problem is the patriarchy, and I think everybody that’s not a rich white male suffers under it. So I don’t think feminist is a radical enough term for what I am. I’m a confrontationalist.”

After noticing that her artistic friends seemed particularly likely to suffer from what she terms “mental collapse” brought on by sociopolitical ills, Lunch (with filmmaker Jasmine Hirst) has recently been working on finishing a documentary, Artists: Depression, Anxiety and Rage. In it, Lunch interviews numerous musicians, artists, and writers about their psychological and emotional struggles, as well as their advice on coping strategies.

For her part, Lunch dealt with childhood trauma by creating avant-garde songs and scathing spoken word performances, which in turn became her livelihood. “My rage, I take it to the stage,” she says. “My rage is on a humongous level. It’s not on a personal level. I’m dealing with societal issues, but I’m hoping to inspire the individual.”

Her outspoken subversion is front and center on the more than seventy albums on which she’s appeared (as a solo musician, spoken word artist, band member, or collaborator), along with her prolific work as a writer and actress.

In 2019, director Beth B made a documentary, Lydia Lunch: The War Is Never Over, so named because, Lunch says, “I have been screaming about the war, which I think is many things. The war against the individual. The war against women. The war against minorities. The war against immigrants. The war against poor white men. So to me, the war is never over.”

She juts out her chin, defiant, when asked how, nearly fifty years into her career, she is able to stay motivated to keep fighting. “The problem doesn’t go away,” she shoots back. “Why should I?”